Xi Jinping visits the media in February 2016 and reportedly tells them "you are the Party's media." Noted businessman Ren Zhiqing scoffs at the Chinese leader's claims and in short order Ren's social media accounts are shut down. Criticism of Ren starts, but then mysteriously stops. What is going on in China's media today?

---

No Twitter. No Facebook. No YouTube. Heavy censorship. Frequent arrest of rights lawyers. Harsh crackdown on activists and opinion leaders. The (Western) discussion on the Internet and social media in China often falls into a "state-versus-society" discourse to the exclusion of all else.

These human rights concerns are well founded. Beginning last year, the Communist Party of China (CCP) has launched one of its widest crackdowns on Chinese civil society, detaining leading human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang with over 280 law firm staff, human rights activists, and family members. Targets have been questioned, summoned by authorities, forbidden to leave the country, held under residential surveillance, criminally detained or have simply disappeared. Pu, once a leading opinion leader on China's Twitter-like service Sina Weibo, has been banned from all microblogging platforms since February 2013 after he publicly criticized now-imprisoned Zhou Yongkang, the retired senior leader of the CCP.

China's highest court also ruled that every social media user in China is subject to defamation charges and a possible three-year prison term if s/he spreads rumours or posts defamatory content that attracts more than 5,000 hits or is reposted more than 500 times. More recently, the formation of the Central Internet Security and Informational Leading Group in February, 2014, and the published draft of China's New National Security Law in July, 2015, have both added to concerns about the CCP's authoritarian rule over the Internet.

Yet there is more to China than state repression, as evidenced in its bourgeoning social media scene on the Internet. At the same time as the crackdown at home, Chinese President Xi Jinping, during his latest visit to the U.S., met with global Internet giants such as Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, the social media platform banned in China. At the meeting Xi promised to "create a new open economic system, push forward reform of foreign investment management and greatly reduce the restrictions on foreign investment." Meanwhile, millions of Chinese busy themselves with Internet shopping, book taxis and travel tickets online, keep in touch with friends, swap photos, watch cat videos and carry on lively chat-posts and debates on Weibo and Weixin (WeChat).

In this essay, we ask: What is the real story behind China's governance of the Internet? How does social media, which some perceive to be a democratizing tool, work in authoritarian China?

Contrary to some China watchers in the West, who often focus specifically on the political use of microblogging sites like Sina Weibo, we argue that social media on its own will not necessarily lead to an increase in civil society activism and challenges to the state. Activism exists, but it represents only a fraction of China's social media story. Chinese social media use is likely to remain largely non-political. Yet such dominance of non-political social media use does not entail total Chinese state repression of digital activism. Chinese social media users have found creative ways to evade direct censorship, and the Chinese state has sought to engage with critical online voices.

The essay proceeds as follows:

- First, we provide key background on the development of the Internet and social media in China.

- Second, we review four defining features of social media in China: the move from copy-cat to China model, the diversity of the social media landscape, the dominance of non-political social media activities, and the process of creative online adaptation by activists and the state.

- Finally, we conclude by suggesting how Canadians might best "read" China's social media.

The Development of the Chinese Internet and Social Media

The influence of social media is first and foremost based on the sheer scale of China's Internet, the development of which can be divided into three phrases. The first period is from 1987 to 1994, during which the first cable was built to connect China to the global Internet, and email exchange was realized with Europe and North America.

The year 1995 marks the second period of China's Internet development, when Peking University, Tshinghua University, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences jointly built an information super highway for China. The online infrastructure increased Chinese Internet speed to 64kbps and the domain name ".cn" registration was set up for China.

The third period starts in 1995 and continues to the present, a period in which the Internet has transitioned to commercial use and is readily available to ordinary people. According to the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC), by the end of the 1990s, there were over four million Internet users in China; in less than three decades, the figure has grown to exceed 668 million (as of July 2015), outnumbering the entire Canadian population twenty to one. Almost 90 per cent of Chinese users — 594 million — access the Internet via their smartphones or tablets.

China also has the world's most active social media population, as described in a 2012 report by McKinsey. According to Statista, every six out of ten Internet users in China is using social media, from blogs and social-networking sites to microblogs and online shopping. The number of social media users in China is projected to surpass 500 million among its 1.4 billion population by 2017. That's roughly equivalent to the combined population of the EU member states. In addition, online users spend more than 40 per cent of their time online on social media, a figure that continues to rise rapidly.

From Copy-Cat to China Model

The defining feature of the social media boom in China is the C2C – Copy-Cat to China – model. Thanks to the 'Great Firewall,' which is intended to block selected websites (such as Facebook and Twitter) and filter keyword searches initiated within mainland China, China's social media is imprinted with Chinese characteristics. For every foreign product or company, Chinese users are often able to find a domestic replacement or equivalent quickly and conveniently.

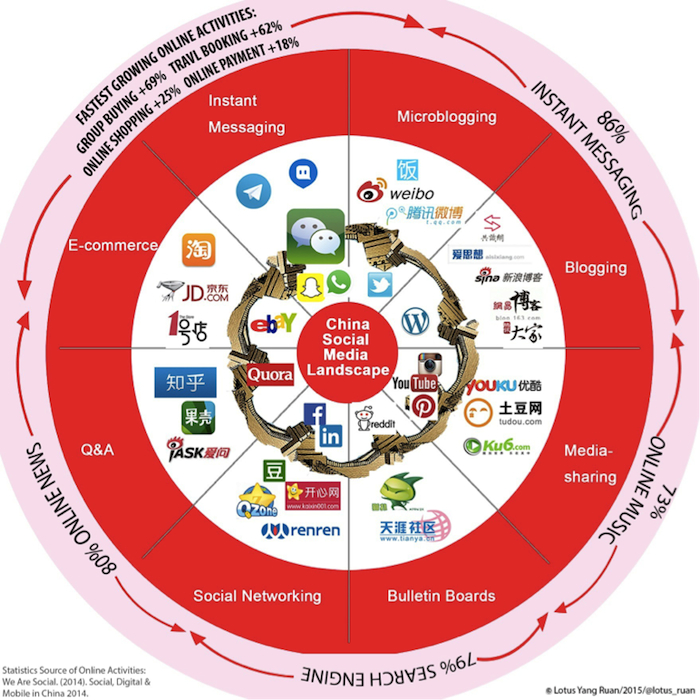

The degree of copying varies from offering identical functions (for example, Fanfou, China's first major Twitter-like service), cloning names and looks (for example, Xiaonei, later known as Renren, which looked exactly like Facebook), to localizing foreign services and tailoring them to Chinese consumers (for example, WeChat). Some of these Chinese platforms are more successful and out-compete their foreign doppelgangers in the Chinese market (See Figure 1: "China' Social Media Landscape").

Figure 1 China's Social Media Landscape

(Note: The percentages indicate how many Chinese Internet users use particular social media function(s).)

WeChat (Weixin in Chinese), for example, is one of the rising Chinese platforms that has transcended Whatsapp, its prototype in the West. Positioned as an instant messaging social media platform, WeChat fulfils the social features of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Skype and a walkie-talkie. According to Global Web Index approximately 73 per cent of Chinese Internet users reported that they have used WeChat in the past month. Owned by the Chinese Internet giant Tencent (Tengxun in Chinese), WeChat was the fastest-rising app between Q1 2013 and Q1 2014, and according to a Global Web Index social report, "could easily become the first non-U.S. social platform to enjoy the type of global coverage previously achieved only by names like Facebook." It went global after rebranding itself from "WeiXin" to "WeChat" in 2012. So far, the mobile application is available in 18 languages including English, Russian, Indonesian, Spanish, Portuguese, Thai, Vietnamese, and Chinese.

A Diverse and Disaggregated Landscape

China's social media landscape is huge, diverse, and disaggregated. So are its users. The political power of social media has been emphasized repeatedly by China watchers, from serving as a virtual public sphere and fostering a civil society that fights against unchecked state power, to pushing forward institutional and democratic changes. Cyber-optimists considering the political omnipotence of information and communication technologies have looked to the Arab Spring in the Middle East, the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong as exemplars of a potential social media revolution in authoritarian China.

It is true that social media has made public discussion on social issues possible. This is especially true of Sina Weibo, where users with similar interests can connect with each other without time and space constraints, and where influential commentators (like Ren Zhiqiang) can post to millions of "followers" instantly. It is also true of the national discussion across all forms of social media over China's air pollution problem initiated by former China Central Television news broadcaster Ms. Chai Jing's documentary, Under the Dome, bottom-up oversight of government officials (e.g. the watch hunt led by Mr. Wu Dong, more widely known as Boss Hua, who brought down a local official after discovering the latter had over 10 luxury watches), and sometimes urban mobilization (e.g. protests against the construction of PX plants in various cities that are part of China's rising NIMBY movement).

Meanwhile, intellectuals and academics make frequent use of social media, from blogs and web portals where their essays are posted and collected, to WeChat groups (smaller in size than the now-restricted Weibo, but good for connecting small groups in conversation). Under current constraints most users do not openly dissent, but criticism and the search for "what can we do?" are evident in these posts and dialogues. To consider social media in China monolithically as a political force and all Chinese social media users as online activists, however, distorts our understanding of what is happening on China's Internet.

China's Non-political Social Media

A third defining feature of social media in China is that politics is a minority topic. The use of social media tools does not have a single preordained political outcome. As Dr. Yuezhi Zhao, communication professor and Canada Research Chair at Simon Fraser University, argued in a previous Canada-Asia Agenda article, social media by itself is far from enough to bring about a "Weibo revolution" in China.

Just as social media in the West can be divided into different sub-categories based on functionality, so can Chinese social media. Not only are there a number of microblogging sites other than Sina Weibo, but social media itself is an aggregated concept that covers blogging (Sina Blog, Tencent Dajia, Ai Sixiang), social networking (QZone, Kaixin, Ddouban), media sharing (Youku, Tudou, Meipai), bulletin boards (Tianya, Maopu), question-and-answer forums (Zhihu, Guokr), instant messaging (WeChat, QQ), online shopping (Taobao, Jingdong), and various other services.

Microblogging, however often it is quoted in Western mainstream media, only appeals to around 30 per cent of the total Chinese Internet users, according to CNNIC. The majority of Chinese Internet users simply use social media for their social life, online shopping, or self-amusement (i.e. watching videos and playing games). China's Internet offers highly-commercialized and entertainment-driven environments. As a 2015 Kantar report shows, over 95 per cent of people's reading time on WeChat, for example, is devoted to celebrity gossip, lifestyle and fashion, personal connections and other non-political topics. And, the top three popular WeChat public accounts are, in descending order, "Funny Video," "Life Helper," and "Care for Gossip."

As such, the dominant impression of China's social media in the West as a major force for political resistance and for promoting democratization is as misleading as depicting Canada's social media as dominated solely by our own political debates. Politics is there and it is important, but it does not engage most people on the Net. This is important for our understanding of China because we currently overestimate the political impact of social media and underestimate its use for pure private communication.

Creative Adaptation by Activists and the State

There are cyber-pessimists who believe that China's governance of the Internet is all about state surveillance and that the CCP's "wars on social media" are constraining the hoped-for power of these tools. To some extent, the CCP is indeed winning its war—if there is one—as data reported in the Wall Street Journal suggests that the Sina Weibo Big V accounts are posting less often than they did in the past—before the 2013 crackdown on these highly influential "verified" Weibo commentators.

But such views are only part of the story. They overestimate the CCP's fear of the Internet and underestimate the creativity of ordinary Chinese social media users that often acts as a counter force to the Party's attempts to manipulate the Internet. The Party seeks to manage rather than dominate, and social media users are savvy "consumers" of political regulations. The repression is real but it is not all-encompassing. The dance between Party and social media users is most often a creative negotiation in which the Party does not always get its way.

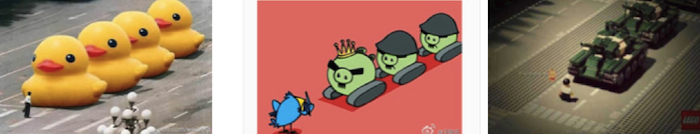

Chinese users have invented an effective system of sarcasm, euphemism, and metaphors to circumvent state surveillance. One of the most outstanding practices is using egao—a style of humour, parody and satire ("e" means "evil" and "gao" means "work") —to mock political inefficacy. Another telling example is the list of vague-sounding appellations for many of the high-ranking officials and influencers within the Party. Before Zhou Yongkang, China's "security tsar," was sentenced to life in prison, his name was blocked in mainland China. Chinese Internet users, however, gave him the nickname "Master Kang" (Kang Shi Fu), a ubiquitous brand of instant noodles in China, to get around censorship. Mr. Jiang Zemin, the former Chinese leader who still tries to exert influence over the Party's decision-making process, is referred to as "the elder" (zhang zhe) or "toad-dy" (ha ha) and Chairman Mao as "preserved meat" (la rou), playing on his corpse preserved in his mausoleum in Tiananmen Square.

In addition to playing around with the keyword filters, the use of images is one way Chinese users bypass real-time deletion on social media. This can be achieved by converting a long text stream into an image file, or using pictures to refer to politically sensitive topics. For instance, around June 4, 2013, a number of re-imagings of the famous "Tank Man" photo were posted on Sina Weibo to commemorate the Tiananmen Movement.

Figure 2 Re-imagining of the June 4 "Tank Man" Photo Posted on Sina Weibo. Image source: Sina Weibo.

Along with the increasing creativity of Chinese social media users is the CCP's more sophisticated management of the Internet. In recent years, the Chinese system of monitoring and management has evolved from a passive keyword filter of incoming Internet traffic to that of a proactive opinion-molder engaged in social media to appeal to the masses. According to China Radio International, by the end of 2014 there were nearly 280,000 government Weibo accounts in China, ranging from Weibo of police departments, China's Supreme Court, to individual government departments and officials.

These accounts publish government reports and interact with ordinary Chinese social media users on a regular basis. While some argue that this is just an attempt to justify and strengthen an authoritarian regime, it is nonetheless a convenient tool for some to connect with government agencies and officials. The CCP has learned, as Anne-Marie Brady has documented in her book Marketing Dictatorship, how to employ sophisticated propaganda techniques to mold domestic public opinion. In recent years this has included savvy use of social media to promote the government's agenda through individual posts by officials and unofficial "50 cent-ers" (paid 50 cents a post to speak as "a regular person" in favour of some government policy), as well as advertising and entertainment aimed to support government policies.

The result is a livelier negotiation between state and society than many imagine. As Zheng Yongnian, director of the East Asian Institute at National University of Singapore, has noted in an interview with a Chinese newspaper, the CCP often compromises on specific issues with local communities that make themselves heard, often through social media.

Implications for Canada

The diversity and largely non-political nature of social media in China challenges the assumptions of most Canadians that China's citizens are repressed and restive. The image we get from a review of social media use in China is one of activity, energy, amusement and copious commercial activity. As we look closer we do find the political activity and resistance to the abuses of officials, especially in local governments, as well as articulate concern about broader issues such as pollution, food safety, and economic inequalities. It is a rich and diverse universe with contrary voices reflecting a diverse society.

Canadians who want to understand China better can also benefit from the diversity of China's social media. If we listen for more than criticism of CCP authoritarianism (which is real, but after all fixing China is the job of the Chinese) we can hear many intelligent and creative voices addressing problems Canadians also face—pollution, family violence, social injustice, food security. We could all benefit from a greater access to these conversations. There may be no Facebook or Twitter in China, but that does not mean social media is completely muzzled. There is Weibo, WeChat (Weixin) and blogs galore. These new technologies are facilitating Chinese to participate in social issues and, most notably, transforming the way Chinese conduct business. The mobility, easy access, fairly cheap use and large user base of social media in the world's second largest economy paints a hopeful picture for both young start-ups and established corporations and offers a variety of voices for understanding life in China today. Canada has a lot to learn from our fellow social media users in China.

Chinese Social Media for English Readers

Chinese social media is conducted in Chinese, but it is not completely inaccessible to non-Chinese speakers. The following websites provide extracts and selections of Chinese social media content in English.

Weiboscope: a Hong Kong-based Chinese social media data collection and visualization project developed by the University of Hong Kong. One project objective, among many, is to make censored Sina Weibo posts publicly accessible.

Tech in Asia: a Singapore-based media platform that follows Asia's tech community, including social media-related trending topics and growing business in China.

China Digital Time: a U.S.-based bilingual media organization that translates and introduces the codes, metaphors, satire and popular articles on Chinese Internet.

China Dialogues: a London, England-based non-profit, bilingual website that follows news and articles of China's urgent environmental challenges.

Tea Leaf Nation: a channel under the U.S.-based Foreign Policy Magazine that follows and analyzes trending topics on Chinese mainstream and social media.