Last month, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s Migration Matters web series delved into migration patterns in two Asian countries: Japan and Malaysia. This month, the series continues with a look at Thailand, a country known for its booming tourist industry.

The diverse range of migratory patterns in Thailand makes it one of the most complex hubs of human movement in the region. The country is a magnet for both migrants and refugees, two very distinct and different groups. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), migrants are persons moving between countries in search of a better life, whether it be for work, education, family reunion, or other reasons. Refugees are persons fleeing internal conflict or persecution to seek safety in other countries. As such, migrants are subject to the law of the country they reside in, whereas refugees are protected by international law (if the host country is a signatory of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol). Terms such as migrants and refugees have been conflated in the context of the Thai situation, and are often interchangeably used in media and public discussions.

Economic Opportunities for Migrants?

Situated at the crossroads of Southeast Asia, migrants from nearby or neighbouring countries, such as Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, China, and Nepal, have been drawn to Thailand for decades. The initial draw was the multitude of economic opportunities that emerged from annual growth rates of over seven per cent in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, according to the United Nation’s International Migration Report, there are around 3.9 million migrants in Thailand. Most of the people who immigrate are workers who take jobs that Thais tend to reject, such as work in the fisheries and construction sectors.

However, immigration policies have been tightening in recent years, and the Thai government has been making concerted efforts to identify and deport undocumented migrant workers. Beginning in 2015, the government increased the fine for migrant workers who overstayed their visas, and subsequently deported thousands after their visa expiration date. In July 2016 alone, 10,000 undocumented migrant workers from Myanmar were arrested by immigration police over a period of ten days. Why are these mass deportations happening, and what does it tell us about the migration policy in Thailand?

One of the major challenges migrant workers face is the lack of basic labour rights. Under Thailand’s Labour Protection Act, working migrants are entitled to the same labour rights as Thai nationals. The reality, however, is that migrants are not always treated equally. According to labour rights activists, many face difficulties obtaining the minimum wage or getting minimal one day off work per month. Many are not covered by accident compensation plans or pensions, and do not have access to adequate health care. Some migrant workers have even become bonded labourers after employers seized their immigration documents.

Thailand also faces the challenge that many of the undocumented migrant workers who end up in the country are trafficked from other countries. For example, more than 90 per cent of workers in Thailand’s billion-dollar fishing industry come from neighbouring countries. Many of them are trafficked and forced to work backbreaking jobs. Should trafficked workers in Thailand be considered migrants? At the moment they are not, and as such are not protected by law.

Safe Haven for Refugees?

Given the current global refugee crisis in Europe, it is helpful to view the larger picture through the lens of Thailand’s challenges. Most refugees in Thailand are currently from Myanmar, and have been coming into the country since the 1980s. These refugees are based in one of nine official refugee camps on the Thai-Myanmar border, where many of them have lived for most of their lives. Today, around 150,000 Myanmar refugees live in these camps. The majority of them are Karen, an indigenous group with origins from eastern Myanmar.

As is the case for migrants, refugees in Thailand also deal with a number of difficulties. One of the most challenging is the harsh restrictions on freedom that all refugees must face. Forty per cent of the inhabitants in refugee camps are not registered by the government as “refugees,” since the government does not have enough money to screen or register them, and are therefore regarded as illegal. The other 60 per cent that are registered also face restrictions on their freedom, since the Thai government has not yet signed the 1951 UN Refugee Convention that sets out the rights of refugees and the responsibilities of countries that host refugees. These registered refugees, therefore, cannot leave the refugee camps, earn income, or provide good quality education to their children. Instead, many of them are dependent on aid agencies.

Since the start of the administration of Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar this year, UNHCR and the Thai and Myanmar governments have been working together to repatriate Myanmar refugees living in refugee camps in Thailand. In October of this year, the first voluntary return after over 30 years was successfully organized. Ironically, during this period of repatriation, other Myanmar refugees citizens fled to China and Bangladesh, seeking to escape emerging conflicts between ethnic armed groups and the Myanmar military.

Tensions between Thai Nationals, Migrants, and Refugees

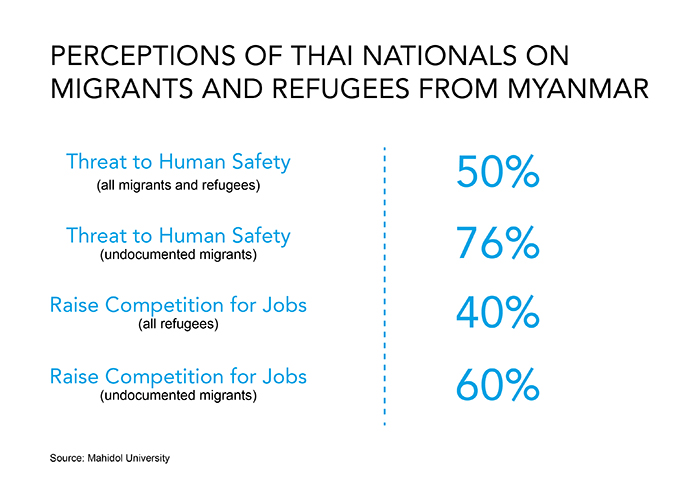

Thai nationals have been living together with migrants and refugees for many years. Even so, the public does not have an entirely positive view of them. A survey by Mahidol University in Thailand found that half of the respondents believed that migrant workers and refugees from Myanmar posed a threat to their safety. Sixty per cent also felt undocumented migrant workers were competing with them for jobs. Even 40 per cent of all respondents thought refugees were competing with them as well, despite the fact that refugees are not legally allowed to work.

Many of these opinions on migrants and refugees are shaped by the Thai media, which portrays them as troublemakers, a threat to safety, social order, and public health, and a burden to Thailand. As a result, many Thais feel that government policies for migrant workers should be tightened. An International Labour Organization (ILO) survey found that 80 per cent of Thai respondents felt this way.

The future looks dim for this Southeast Asian migration hub. In the near future, one of the biggest challenges for the Thai government will be making sure everyone’s voice is heard. Enhancing public dialogue on migration and refugee issues will be essential in charting the way forward for Thailand’s migration policies.

To explore other posts in our Migration Matters series, please click on the links below:

Migration Matters: Project Overview

Migration Matters: Malaysia

Migration Matters: Japan