Of all the latest buzzwords in the financial technology (fintech) and banking fields, ‘digital currency’ represents one of the fastest growing revolutions in this space. Digital currency, also known as digital money or electronic currency, refers to currencies and money-like assets exclusively in electronic form, and includes cryptocurrency, virtual currency, and central bank digital currency (CBDC).

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact global trade and financial exchanges, many countries around the world, driven by a sense of urgency to go digital, have been increasingly exploring the integration of this new currency form. Unlike Bitcoin, a cryptocurrency that is decentralized in nature, a CBDC gives a country’s monetary authority the ability to regulate it and to back it with reserves, enhancing financial security for users and also ensuring the central bank’s control over money supply. Although no country has formally launched a CBDC to date, central banks in more than 60 countries – including Canada, Japan, Russia and the U.K. – have either been conducting feasibility studies or pilot projects to assess the possibility of integrating digital currency into their national banking system. Among all major economies, China is ahead of others today in the pursuit of issuing a CBDC.

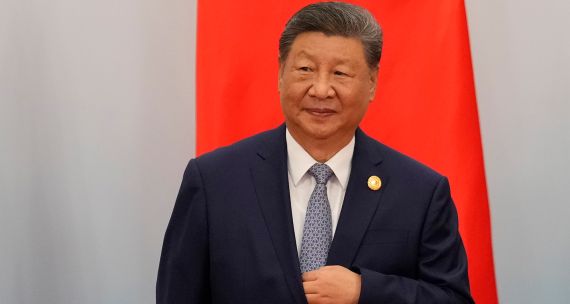

China Aims High for Digital Renminbi

China’s exploration of the digital yuan (also referred to as the e-CNY or digital renminbi) can be traced back to 2014, when People’s Bank of China (PBOC) – the Chinese central bank – began researching a possible Chinese digital currency. In 2017, it formally launched the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DC/EP) research project with support from the ‘Big Four’ state-owned commercial banks and three major telecom operators, taking the digital yuan from concept to actual development. Since its first testing in April 2020, the digital yuan has been made available for select participants in 10 cities across China to make retail payments through the DC/EP pilot program. By July 2021, the ‘white list’ of those eligible to participate in the trials has expanded to 10 million residents. Those on the white list can sign up for a lottery when their city government launches its pilot program, and winners of the lottery receive, through the digital yuan official app, a one-time C$40 red packet that can be used for small-ticket purchases through a range of participating merchants, such as shopping malls, food and beverage outlets, online shopping platforms, and public transit systems. One recent pilot scheme was rolled out in Beijing in June 2021, with the city government distributing 200,000 red packets for a total value of C$7.8 million.

China has one of the world’s most sophisticated fintech scenes, with already near-ubiquitous adoption of mobile payment solutions. This leads many to question if the creation of digital currency is a move by the state to end the Alipay/WeChat Pay duopoly over more than 90 per cent of the digital payments currently taking place in China. But such arguments confuse the CBDC, a form of currency, with mobile payment tools, which are more wallet-like and form part of the infrastructure supporting the use of currencies. Far from a zero-sum game, digital yuan and mobile payment platforms are likely to co-exist and complement each other across a number of payment scenarios. The country’s two major ‘third-party’ e-payment services providers, Ant Financial and Tencent, will also play a role in facilitating the circulation of digital yuan as it approaches the reported 2022 broad circulation. Alipay announced in May the addition of a digital yuan wallet, making this trial-phase CBDC accessible in its app.

Domestic Rationales Behind the Digital Yuan Drive

One of the reasons behind Beijing’s push for digital yuan is that it will allow state-owned banks to better capture consumption data and insights – the majority of which is now owned by privately-owned payment platforms in a collection process that largely bypasses the formal banking sector. The Chinese central bank’s desire to regain control of payment data and consumption insights is aligned with Beijing’s larger efforts recently to crack down on antitrust behaviour and monopolistic market practices that it alleges have emerged among its data-wealthy and ever-growing tech giants.

Another motive behind Beijing’s CBDC drive is to enhance the stability of its financial system. Citing concerns about the potential risks related to virtual currency speculation and the weakening of its regulatory oversight, Chinese financial authorities have been holding a strong line against the use of foreign cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin. With Bitcoin trading and initial coin offerings completely banned in 2017, Chinese financial authorities have now diverted their attention to cracking down on Bitcoin mining in the country, which it sees as not only encouraging speculative activities but also causing environmental concerns, due to the energy-heavy nature of crypto-mining.

To differentiate the digital yuan program from these existing cryptocurrency systems, Beijing is creating different personal identification/authentication levels to protect users’ anonymity for most small-ticket transactions. As details get hammered out, the government hopes that such design could enhance digital yuan’s convenience, safety, and legitimacy in the eyes of today’s increasingly privacy-conscious Chinese consumers.

Digital Yuan on the International Stage

Although PBOC officials on multiple occasions have stressed that the priority for its digital currency program is to promote its domestic use, what China is attempting to achieve with a sovereign digital currency is probably far beyond uses within its border. Having engaged in a renminbi internationalization effort for more than a decade after the 2008 global financial crisis, PBOC made various attempts to expand the renminbi’s use in international trade settlement and saw some, but less-than-ideal, progress. Despite its 2016 inclusion in the IMF special drawing rights basket, a group of prominent currencies used for the Fund’s global reserve asset, renminbi only accounted for 2.16 per cent of global trade payments and 2.25 per cent of official foreign exchange reserves by the end of 2020 – dwarfed by the country’s 15 per cent share of global trade.

Using a domestic digital currency for international transactions and clearing could arguably represent much broader gains for China than the currency’s use at home, and doing so ahead of other countries will give China the first-mover advantage to gain traction and effectively bypass currency conversion, thereby reducing foreign exchange costs and uncertainties in deals between mainland Chinese companies and their trading partners. It is widely believed that Beijing’s end goal is to reduce the dominance and seigniorage that the U.S. has been enjoying, since the U.S. can simply print the currency that other countries demand for international transactions and continue to run a trade deficit financed by others, something it has been doing for many years. The PBOC has allied with a number of cross-border partners since it joined (in February 2021) the Central Bank Digital Currency Bridge project, which aims to support real-time cross-border foreign exchange transactions using digital technologies. The PBOC could potentially test cross-border transactions for its digital yuan with the project’s members, including the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, central banks of Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates. This multinational project is further supported by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) network, which has 63 central bank members around the globe.

Conclusion

While actively expanding the scope of its central bank digital currency pilot program, the People’s Bank of China appears to be moving cautiously as it tries to tackle the same policy conundrum that other central banks face – finding the right balance between ensuring privacy and effectively monitoring the risks, such as money laundering and tax evasion, that could stem from anonymity. The PBOC has stressed repeatedly that it wants to build a sound digital currency infrastructure and a proper regulatory environment before a full roll-out. Given that the initiative comes from the central bank, the digital yuan, once formally launched, will likely be managed differently from better known cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Observers are keeping a close eye on the outcome of the project, particularly whether China will be able to promote the digital yuan as an attractive form of reserve currency and, thus, successfully boost its cross-border usage to challenge the long-standing U.S.-dollar-dominated system. For one thing, the PBOC’s planned pilot for digital yuan at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics will be a key step towards the global acceptance of this new form of currency.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) has also launched several projects to build its capacity and lay the groundwork for issuing a Canadian CBDC. Acknowledging that the decision point will probably arrive sooner than expected because of COVID-19, the BoC wants to ensure that its own version of digital currency is safe, universally accessible, resilient, and efficient, while at the same time allowing for monetary sovereignty. Placing the importance of a global regulatory framework front and centre, the Canadian central bank is working with like-minded peers in a seven-member group (including the central banks of the U.K., Japan, the European Union, the U.S., Sweden, and Switzerland, plus the BIS) to discuss principles and features – including cross-border interoperability – around the issuance of a CBDC. In this regard, understanding how China is designing its digital currency and the potential implications when it is eventually launched for cross-border transactions, even though the two central banks are different on many levels, is both timely and important.