Canada and Japan have deep roots that date back to the opening of Canada’s diplomatic office in Tokyo in 1929. Fast-forward almost 90 years and relations are still steadfast. Ottawa has stressed that, “improving trade relations with Japan is a top priority for [the Canadian] government.” To demonstrate this, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made an official visit to Japan in May 2016 and met with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, as well as the emperor and empress of Japan.

But Canada-Japan relations were not always as rosy. Compared to the warmth and acceptance most immigrants to Canada experience today, many of the first Japanese immigrants who arrived in Canada in the early 20th century were met with racism and prejudice. [1]

Today, both Canada and Japan have looked beyond their sometimes-turbulent past.[2] The two countries have instead developed a lasting and expansive relationship by focusing on areas of mutual benefit.

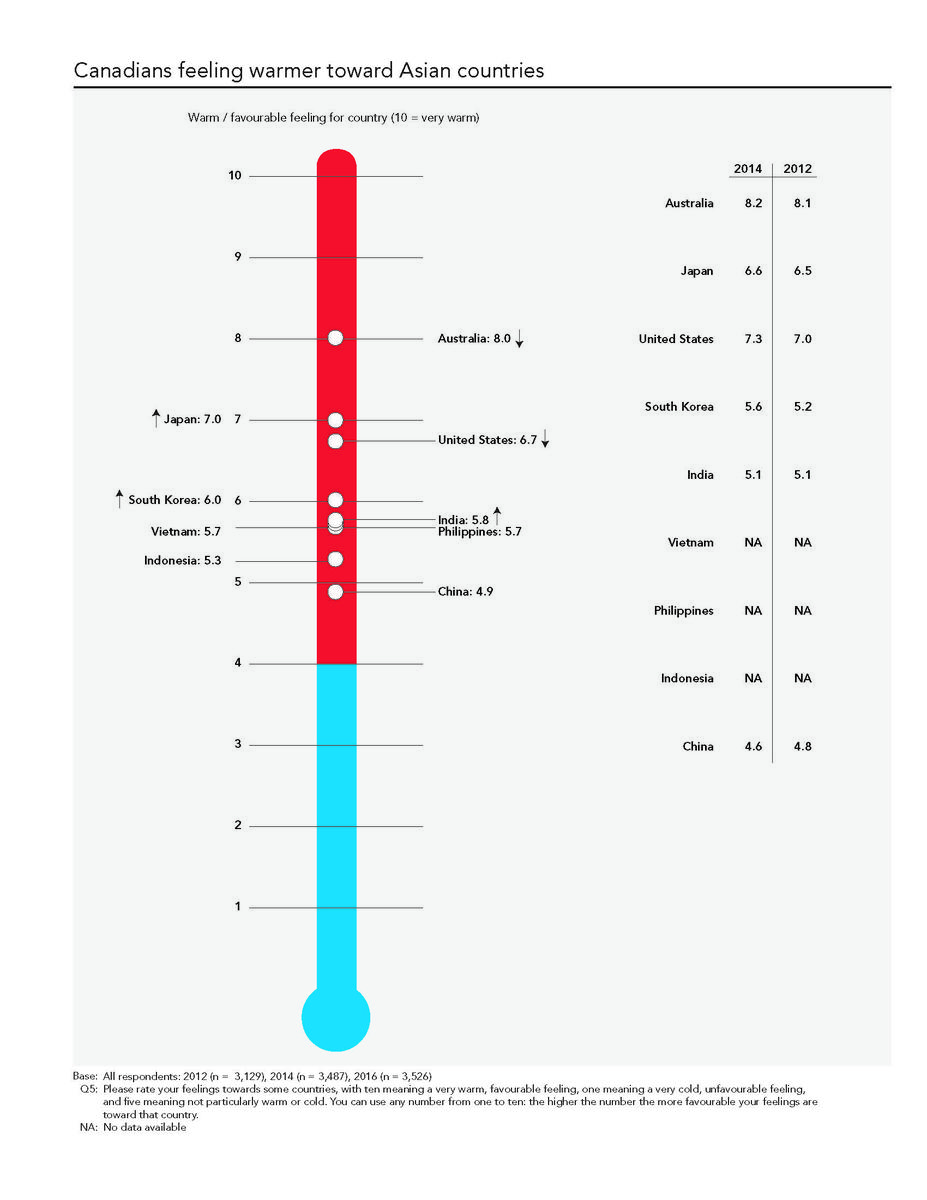

These growing ties have had a strong impact on Canadian public opinion. According to the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s 2016 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Asia (2016 NOP), after Australia, Canadians have the warmest feelings toward Japan. Remarkably, Canadians have even more positive feelings toward Japan than they do toward their southern neighbour, the United States.

Notwithstanding the good relationship that exists today between Japan and Canada, there is room for closer engagement in 2017 and beyond, particularly in trade, investment, educational exchanges, and in partnering on strategic interests.

1. Foster Two-Way Trade

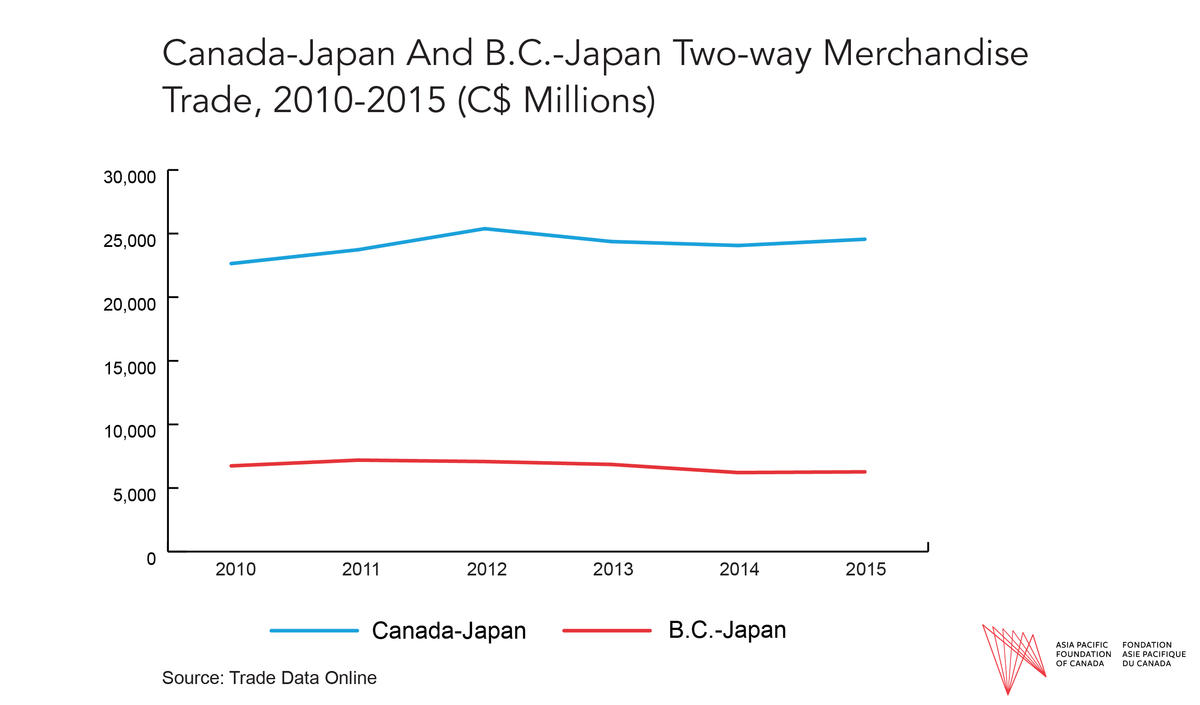

Two-way merchandise trade continues to increase year after year, with Japan being Canada’s fifth-largest trade partner in the world, and second-largest in Asia after China. Japan is extremely dependent on Canada’s canola seeds, potash, various wood products, gold, and wheat and cereals. Evident in the driveways and living rooms of almost every Canadian home, motor vehicles and vehicle parts, and electrical and electronic machinery and equipment are Canada’s largest imports from Japan.

Still, there remains a lot of untapped potential in the Canada-Japan trade relationship. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) would have been the best opportunity to advance economic relations, but there is a distinct possibility that the TPP will not go the final mile given U.S. president-elect Donald Trump’s opposition to the agreement. The next best option may be for Canada and Japan to realize economic opportunities through renewed negotiations on a Canada-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (CJEPA), which has similarities to a free trade agreement (FTA). This may be for the best after all since, according to the 2015 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Canadian public is more open to an FTA with Japan (70%) than the TPP (41%).

2. Encourage More Two-Way Investment

Two-way investment between Canada and Japan has continued since Japan’s economic rise. According to both the 2016 NOP and the 2015 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Asian Investment, more than three-quarters of Canadians are supportive of investment from Japan, associating it with new technologies, economic growth, and job creation.

These days, Japanese investment into Canada is far surpassing Canadian investment into Japan. In 2015, Canada only invested C$8.3 million into Japan, while Japan invested C$22 million into Canada. In the years to come, although Japanese investment should continue to be supported, Canadian investment into Japan should be encouraged in an effort to balance the investment relationship.

3. Increase the Number and Quality of Educational Exchanges

Student flows have helped strengthen Canada-Japan relations through the years. Canada welcomed close to 5,800 international students from Japan in 2014. Meanwhile, only three per cent of Canadian students venture overseas to study abroad, with only a fraction of those choosing Asia as a study destination.

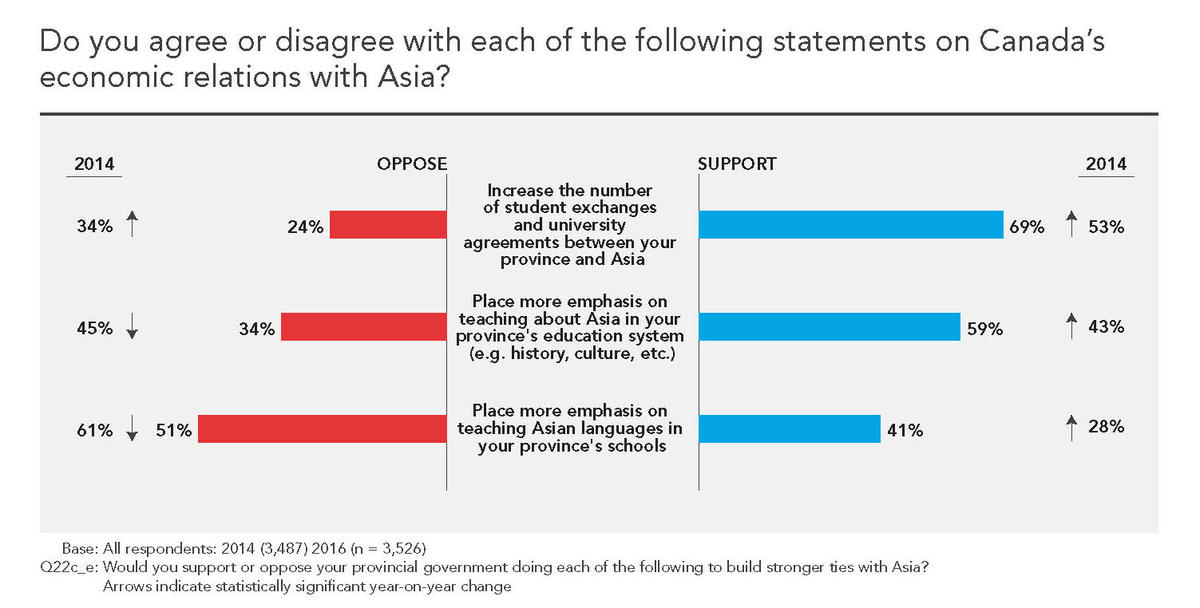

The Canadian public is now realizing how important it is for young Canadians to study abroad in pivotal countries like Japan. The 2016 NOP results show that almost 70 per cent of Canadians think their province and Asia should increase the number of student exchanges and university agreements. APF Canada has already tried to do this by partnering with the Government of Japan to deliver its Kakehashi Project, which selects a number of Canadian students and Japanese students for a cultural and academic exchange designed to promote deeper mutual trust and understanding between the people of Canada and Japan.

4. Partner on Strategic Interests, such as Clean Energy and the Environment

Lastly, Canada and Japan share many similar strategic interests that both countries can work on together to achieve common goals. One such interest that has become increasingly important is clean energy and the environment. The past Canada-Japan Joint Economic Committee Meeting in October 2016 emphasized future collaboration on clean energy and the environment, and both governments agreed to double investment in clean energy innovation over the next five years.

There are a number of already-established scientific partnerships between Canada and Japan. One of these is the Mitacs-Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Summer Program, which supports graduate students in Canada to pursue collaborative research in Japan in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. To further collaboration in clean energy and the environment, more R&D opportunities should be made available between Canadian and Japanese businesses, universities, and research institutes.

With a prime minister who is avidly advancing Canada-Asia relations, and with growing uncertainty to the south, the time is right for deepening Canada-Japan relations. And fortunately, contemporary Canadians are overwhelmingly supportive of building on the strong foundation that has been established through a long and tested friendship.

[1] In the early 20th century, rising anti-Asian sentiment in British Columbia prompted the Canadian government to tighten restrictions on Japanese immigration. On top of this, Canadian law denied Asians the right to vote and work in most professions. The expansion of the Japanese empire in the 1920s and ’30s intensified these sentiments, leading to widespread expressions of a ‘yellow peril.’ With the arrival of World War II, more than 21,000 Japanese Canadians were perceived as enemies and forced to move into internment camps. Families were torn apart and property – including real estate holdings, fishing boats and other chattels – was confiscated and later sold. It would take four years after the war was over before all the restrictions were lifted and Japanese Canadians given full rights of citizenship.

[2] In 1988, Japanese Canadians were given a formal and sincere apology from the federal government, one of the first ‘victories’ in a minority’s struggle to overcome persecution in Canada.