September 30, 2021 marked Canada’s inaugural National Day for Truth and Reconciliation – a day to reflect, learn, and help steer our country in a new direction. In this spirit, our September 30 Special Edition of Asia Watch focused on Indigenous peoples in the Asia Pacific, and is republished here as an APF Canada Dispatch.

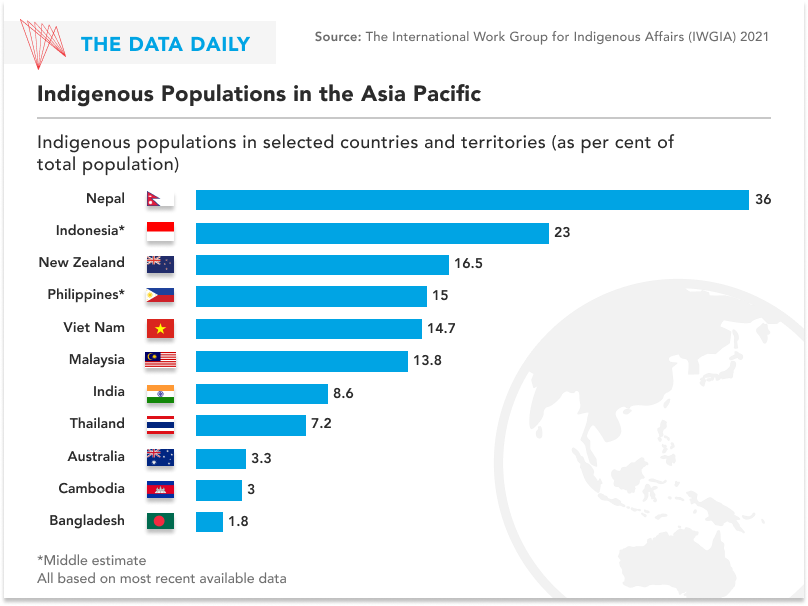

The Asia Pacific is home to some 300 million Indigenous peoples, a staggering 70 per cent of the world’s total. Similar to the situation in Canada, Indigenous peoples throughout the region face myriad complex health, social, political, and economic challenges wrought by the expansion and creation of states, colonialism, cold and hot wars, and legacies of associated traumas. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified these challenges.

In 2007, all countries in the region (except Bangladesh, which abstained) voted in favour of the United Nations Declaration on the World’s Indigenous Peoples, the most comprehensive international document on Indigenous rights. And yet, many states in the region do not recognize the presence of Indigenous peoples within their borders. In those that do, there are often stark contrasts between tabled laws and policies and their implementation. In short, truth and reconciliation take different forms across the region.

There is much to celebrate in the Asia Pacific as Indigenous peoples, like those in Canada, are leading the way in asserting their rights and advancing action and dialogue toward truth, reconciliation, and revitalization. For example, the International Decade of Indigenous Languages will begin next year and help foster the thousands of Indigenous languages spoken, including in the Asia Pacific region. Indigenous economies and businesses are also gaining traction through Indigenous-led initiatives and networks, such as the efforts to include Indigenous business in policy discussion through the work of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

While the following four stories cannot account for all Indigenous Asia’s uniqueness, complexities, and diversities, they offer insight into some challenges and opportunities for select Indigenous populations in the region. We hope these stories provide an opportunity for reflection and contribute to reconciliation here and throughout the region.

Taiwan's Rocky Road Toward Indigenous Recognition and Justice

Indigenous peoples feature in new narratives . . .

Seqalu, a drama about a conflict between Indigenous groups and other peoples in 1860s southern Taiwan, is one of the first programs to pop up on TaiwanPlus, a new state-sponsored media platform for international audiences. The series, which features famous Indigenous actors, has become hugely popular domestically after airing on public television. Critics hailed it for offering a new narrative of a multiethnic Taiwanese history. Some Indigenous commentators noted that showcasing Indigenous languages and stories could spark new interest in learning about Taiwan’s unique history. Others have criticized the sidelining of Indigenous struggles in favour of an assimilating multicultural narrative. Regardless, Indigenous stories are becoming the face of Taiwan’s domestic and international image.

The rise of Indigenous transitional justice . . .

Indigenous peoples have inhabited the island of Taiwan for thousands of years. Today, they number more than 560,000 and comprise 16 officially recognized ‘tribes’ and several others seeking recognition. After centuries of land dispossession, oppression, and resistance, an Indigenous renaissance began in the late 20th century. Taiwan has since created the Council of Indigenous Peoples, signed a ‘New Partnership’ treaty, and passed an Indigenous Basic Law. In 2016, newly-elected President Tsai Ing-wen launched a transitional justice campaign which included an official apology to Indigenous peoples and the launch of the Presidential Committee on Indigenous Historical Justice and Transitional Justice (ITJC). Still, the ITJC has been plagued with funding issues and land restitution has encountered obstacles. In May, a landmark Constitutional Court decision subordinated the Indigenous Basic Law when it upheld restrictions on Indigenous hunting.

The other Taiwan question . . .

Indigenous voices in Taiwan are diverse, as are the political priorities and tactics of Indigenous peoples. For example, representatives on the ITJC told People’s Republic of China (PRC) President Xi Jinping in 2019 that “we have never given up our rightful claim to the sovereignty of Taiwan.” Conversely, the negative experiences of some Indigenous peoples under Taiwan’s government have led them to support the PRC. Indigenous voters have historically backed the Kuomintang (a conservative party that ruled Taiwan as a dictatorship for more than five decades), but younger generations are now shifting to President Tsai’s Democratic Progressive Party (a liberal party that emphasizes local Taiwanese identity) and ‘third force’ parties (which mainly originate from progressive social movements). Indigenous issues go beyond the ‘Taiwan question’ and the aforementioned 'three forces’ of Taiwan’s politics. For many, the fate of Taiwan’s status is secondary to more immediate issues such as land restitution and self-determination.

READ MORE

- 親愛的漢人 (Dear Han People): Episode 8: 滴血驗親救台灣 (podcast, in Taiwanese Mandarin)

- g0v: Joint declaration by the representatives of the Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan serving on the Indigenous Historical Justice and Transitional Justice Committee

- Indigenous Insight: Nation vs. Community: Where does Indigenous peoples’ transitional justice go from here?

New Zealand to Aotearoa: Māori Party Introduces Petition to Change Country Name

Petition garners 25,000 signatures on first day . . .

On September 14, the co-leaders of Te Pāti Māori (the Māori Party) announced a petition to formally change the name of New Zealand to Aotearoa, its name in te reo Māori (the Māori language). The petition, which also calls on Parliament to restore all Māori place names, including names of towns and cities, within five years garnered more than 25,000 signatures in its first 24 hours. Recent reporting suggests over 60,000 people have given their support to the call, while Te Pāti Māori hopes to increase that number to 100,000. The country’s population is about five million.

A petition anniversary . . .

The petition’s opening came on the 49th anniversary of the delivery to the New Zealand Parliament of an earlier petition for te reo Māori to be recognized as an official language of the country. That petition contained 30,000 signatures. In 1987, Parliament passed the Māori Language Act, which enshrined te reo’s Māori’s official status in law. Even though Māori Language Week has been celebrated in mid-September since the mid-1970s, te reo Māori is spoken today by only 20 per cent of Māori and only three per cent of the broader population. In 1910, about 90 per cent of Māori spoke te reo. But by 1950, only about one quarter was able to speak the language after it was systematically suppressed, including in schools.

Te reo Māori contested . . .

Earlier this year, an opposition MP called for a referendum on the country’s name, including that the use of ‘Aotearoa’ be banned on official documents until such a referendum passed. Yet, for many people and companies, the interchangeable use of ‘Aotearoa’ and ‘New Zealand’ is commonplace. Many te reo Māori words, expressions, and cultural concepts are defining features of New Zealand English. Some government ministries are more commonly referred to by their te reo Māori name than their English name, and the country’s national museum, Te Papa, is referred to exclusively in te reo Māori. Yet a recent poll found 58 per cent support for ‘New Zealand’ and 41 per cent wanting ‘Aotearoa’ as part of the country’s name, with 31 per cent preferring ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’ and nine per cent supporting ‘Aotearoa.’

READ MORE

- The Guardian: New Zealand Māori party launches petition to change country’s name to Aotearoa

- New Zealand Herald: Aotearoa-New Zealand name change debate: New poll shows while majority in favour of status quo there is support for change

- Stuff: What’s in a name? Aotearoa-New Zealand debate continues to simmer

Japan’s Ainu Work to Narrow the Gap: From Recognition to Reconciliation

Hokkaido 150 Years Later . . .

An edited volume (in Japanese) entitled Ainu Perspectives on 150 Years of Hokkaido will hit bookshelves next month. It addresses thoughts and reflections about the era since the Meiji Government of Japan changed the name of the northern island from Ezo/Ezochi to Hokkaidō and officially incorporated it into Japan in 1869. In 2018, there was much discussion in Japan and worldwide on the 150 years since Japan’s Meiji Restoration – the birth of the modern Japanese state. But there was significantly less discussion about the 150 anniversary of the renaming of Hokkaido in 2019, and Ainu experiences since then. With few exceptions, neither of these sesquicentennials seriously considered Ainu perspectives, as discourse around Ainu-related (settler) colonialism, historical trauma, and reconciliation remain contested topics in Japan. This new book by Ainu authors, and related events, will make a notable contribution to advancing reconciliation-related discussion.

Ainu Mosir and beyond . . .

The Ainu are Indigenous peoples of Ainu Mosir (“peaceful land of human beings”), which included northern Honshu, Hokkaido, the Kuril Islands, and southern Sakhalin. Today, while most live in Hokkaido, Ainu also live throughout Japan and around the world. A 2013 Hokkaido Government survey pegs the Ainu population in Hokkaido at about 17,000, while other estimates of the total population are around 100,000 or higher. Some Ainu are in the process of rediscovering their heritage, and others choose to be silent about their Ainu identity out of fear of discrimination and related challenges.

Ainu neno an Ainu – 'human like human' . . .

Japan, which had long banned Ainu culture and language, is beginning down a slow path toward reconciliation. The Japanese Government recognized the Ainu as Indigenous for the first time in 2008, and the first law to formally recognize the same came in 2019. As in other places, recognition and laws are only part of the path toward reconciliation. Ainu today continue to proudly pursue their interests and rights in various milieus on topics ranging from art, dance, and music, the return of ancestral remains, fishing rights, and language revitalization. Some of these efforts are highlighted on the recently launched AinuToday platform (below), the first English-language, knowledge-sharing platform for an international audience to learn about contemporary Ainu.

READ MORE

- AinuToday.com: Welcome to AinuToday

- The Economist: Japan’s Ainu people have a new museum. Many feel it omits a lot

- NHK World – Japan: Rediscovering Ainu Heritage: Part 1

COVID’s Third Wave Hitting Indigenous Australians Hardest

Outbreak in the outback . . .

Relative to the wider Australian population, Indigenous Australians were six times less likely to have contracted COVID-19 during the pandemic’s first two waves. But during the ongoing third wave, an outbreak in Wilncannia, a remote outback town of about 700 in western New South Wales, has highlighted the brittleness of earlier successes. The outbreak began at a large Aboriginal funeral in mid-August. By mid-September, nearly 150 people were infected, about 90 per cent of whom were Aboriginal. Local health officials warned the federal government in March 2020 of the need for “urgent and drastic” action to prevent serious COVID-19 outbreaks across the remote region. They now say little was done to prepare.

Indigenous communities most at risk . . .

What happened in Wilcannia underscores the overlapping social and economic factors that make Indigenous Australians more at risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death than the Australian average. High rates of chronic health conditions and overcrowded housing are of particular concern, as are low vaccination rates. While nearly 53 per cent of Australians are fully vaccinated, fewer than one in three Indigenous Australians have received both jabs. Over three-quarters of eligible Australians have received at least one vaccine dose, but less than half of eligible Indigenous Australians have done so.

Will policy responses help?

On September 14, the Australian government announced a new plan to boost vaccinations among Indigenous Australians. The plan identifies 30 priority regions across the country, including urban, rural, and remote areas. It extends an additional C$7 million in funding to enhance engagement with Indigenous Australians and promote vaccine uptake by engaging additional liaison officers and through culturally appropriate messaging. Critics observe that Indigenous Australians were identified as a high priority when the vaccine rollout began, that the quantum of funding is less than transformational, and that the plan essentially promises more of the same. The Australian government has indicated its four-phase re-opening plan will begin in earnest when 80 per cent of eligible Australians are fully vaccinated. Many fear that if vaccination rates among Indigenous Australians remain low, re-opening will usher in a new pandemic of the unvaccinated, disproportionately affecting Indigenous Australians.

READ MORE

- Australia Broadcasting Corporation: Leaked letter warned of COVID disaster in Aboriginal community of Wilcannia 18 months ago

- The Guardian: ‘Scared and angry’: warnings ignored before Delta ripped through Wilcannia

- The Sydney Morning Herald: ‘Woefully behind’: Fewer than one in three Indigenous Australians fully vaccinated