On July 7, Cambodia was informed by the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump of a new August 1 deadline to renegotiate trade terms and avoid steep tariffs. Although the recently revealed 36 per cent duties announced by the U.S. as part of its broader tariff policy are lower than the hefty 49 per cent Washington threatened earlier, they remain significant for Phnom Penh. On April 2, Trump imposed global reciprocal tariffs, unveiling the plan he pointedly referred to as his own ‘Liberation Day’. The July 7 announcement likely came as a surprise, as Phnom Penh believed it had secured a preliminary trade agreement framework with the U.S. just three days earlier.

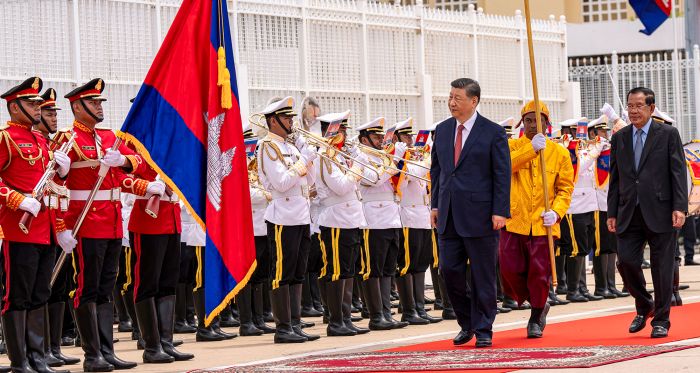

At issue in Cambodia’s relationship with the U.S., however, is more than trade; Phnom Penh’s relationship with Beijing is also a factor. In recent years, that relationship has grown much stronger. China is now Cambodia’s largest trading partner and investor, and an increasingly close partner on defence and security. That co-operation, along with Cambodia’s recent gains from the ‘China + 1’ strategy — whereby global manufacturers shift production to alternative economies to reduce their dependence on China — has drawn scrutiny from Washington.

While there has been some attention to how Southeast Asia’s larger economies are responding to the imposition of U.S. tariffs and the U.S.-China rivalry, less attention has been paid to how smaller and heavily export-oriented economies, such as Cambodia, are navigating these crosscurrents. While Canada’s economic ties with Cambodia are not large enough to offset these trade disruptions, there are opportunities for bilateral co-operation that can support Cambodia’s long-term development goals while helping Canada deliver on its regional commitments through its Indo-Pacific Strategy.

What is Cambodia's trade exposure to the U.S. versus China?

Cambodia's trade relationships with its two largest trading partners — China and the U.S. —reveal a striking asymmetry. China is Cambodia’s largest trading partner overall, with bilateral trade between the two reaching C$21 billion in 2024.

However, this trade flow is skewed toward Cambodian imports of Chinese goods, including machinery, electronics, and consumer products, which account for more than half of the country’s total imports. In contrast, only 15 per cent of Cambodia’s exports are destined for China. In 2024, Cambodia imported goods worth C$18.4 billion from China while exporting only C$2.4 billion, resulting in a substantial trade deficit of C$16 billion.

Trade with the U.S. tells a different story: while slightly smaller in total volume, at C$18 billion, trade flows are more balanced. Nearly 40 per cent of Cambodia’s ready-made garments — the backbone of the economy — are shipped to the U.S., making it Cambodia’s single largest export market. Cambodian exports to the U.S. surged during the first Trump administration, as rising tensions between Washington and Beijing prompted global manufacturers to relocate operations out of China. Between 2017 and 2021, Cambodian exports to the U.S. more than doubled — from C$3.3 billion to over C$7.3 billion — as companies moved production to Cambodia, drawn by its low labour costs, proximity to China, and attractive tax incentives for foreign investors. In contrast, Cambodia’s imports of U.S. goods in 2024 were relatively limited, contributing to a trade deficit of C$16.7 billion.

In addition to this structural difference between these two trade relationships is the critical role of investment. As noted above, China is Cambodia’s primary source of capital and infrastructure investment. As Phnom Penh renegotiates trade terms with Washington, it must carefully navigate its increasing reliance on Chinese funding while maintaining access to Western markets — vital for sustaining its export-driven economy.

How has Cambodia responded to U.S. trade pressures?

Cambodia's response to U.S. trade pressures has been multifaceted, combining limited reforms with a focus on strategic diversification. The first round of U.S.-Cambodia trade talks was held from May 13–15. Cambodian negotiators tried to ease pressure by demonstrating the country’s responsiveness to U.S. threats, proposing a reduction in tariffs on 19 categories of American imports — ranging from automobiles to agricultural products — from 35 per cent to five per cent. A second round of negotiations was held in early June, with both countries agreeing on provisions for a Cambodia-U.S. Agreement on Reciprocal Trade.

On July 4, Phnom Penh announced that a trade agreement framework had been reached; however, a July 7 letter revealed the U.S. still plans to impose 36 per cent levies on Cambodian goods starting on August 1.

Cambodia was previously included in the U.S.’s Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), which expired in 2020 and was not renewed due to concerns about Cambodia’s democratic backsliding and human rights violations. Under the GSP, Cambodia previously enjoyed duty-free access to the U.S. market for approximately 5,000 products, boosting the competitiveness of a wide range of Cambodian exports, including garments, footwear, agricultural goods, and travel products.

What are the opportunities and risks of closer trade ties with China?

Over time, Cambodia’s relations with China have expanded beyond trade to include co-operation in security, defence, and tourism, as well as cultural exchanges. The growing extent of Chinese influence has raised concerns in Washington and cast doubt on the independence of Phnom Penh’s policymaking.

The recent Chinese-backed upgrades to Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base remain particularly contentious, despite Cambodia’s repeated claims that the facility is not intended for exclusive Chinese military use. These concerns have been further heightened by Cambodia’s receipt of two warships from Beijing, part of broader military modernization efforts backed by China.

Another concern for Washington is the rerouting of Chinese goods through Cambodia to circumvent tariffs — an issue that Cambodia addressed by highlighting two new regulations aimed at tightening compliance with rules of origin and preventing the mislabelling of Chinese goods as Cambodian-made.

Meanwhile, Chinese investment has fuelled significant infrastructure development across Cambodia. Projects such as the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville Expressway and the Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone have enhanced connectivity and industrial growth. China also finances nearly 70 per cent of the country's power plants, contributing to a more robust energy grid. These developments, however, come with growing risk: Cambodia's public debt to China now exceeds C$5.5 billion, raising questions about debt sustainability and the erosion of policy autonomy.

What are Cambodia's alternatives?

Cambodia has actively pursued economic diversification beyond the U.S. and China. A possible alternative market for Cambodian exports is the European Union. In 2001, Cambodia was given preferential access to the EU’s "Everything But Arms" (EBA) scheme, which allowed duty-free, quota-free entry for all Cambodian exports to the EU, excluding weapons and ammunition.

In 2020, the EU partially withdrew this scheme, citing democratic and human rights concerns. As a result, around a fifth of Cambodia’s previously eligible exports — including garments and footwear — lost their preferential status, affecting an estimated C$1.6 billion in annual sales. Cambodia could seek to regain access to these schemes to offset market losses, but such a move would require reforms to its human rights practices and democratic governance. However, the government in Phnom Penh has shown little interest in reforming or improving these areas of concern.

Integration with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is also a cornerstone of Cambodia’s diversification strategy. Intra-ASEAN trade now accounts for approximately 28 per cent of Cambodia's total trade. Closer economic ties with Japan and South Korea have also been beneficial, resulting in investments in Cambodia’s agriculture and light manufacturing sectors. Cambodia has also actively leveraged its participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to expand exports to Asian markets, particularly for agricultural commodities such as rice and cassava. Beyond Asia, Cambodia has secured a bilateral deal with the U.K., preserving tariff-free access post-Brexit.

These arrangements, however, have complications. ASEAN's potential as a counterbalance to the U.S. and China is limited by regulatory disparities and competing national interests among member states. For instance, sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures — health and safety rules to prevent diseases and pests in traded food and agricultural products — make up nearly half of the non-tariff barriers limiting both intra-ASEAN and global trade.

Cambodia’s agricultural exports are highly exposed to SPS rules. Recently, ASEAN agreed to lower these barriers to boost regional trade, but longstanding gaps between intention and implementation persist. Furthermore, inconsistent SPS standards across ASEAN countries subject Cambodian agricultural exports to additional testing and certification processes, driving up costs and delaying market access.

There are several areas in which Cambodia could improve domestically. Its inability to meet the stringent regulatory standards of advanced economies hinders its deeper integration with Western markets. Securing the necessary certificates of origin has proven especially challenging for local exporters due to staffing shortages, limited technical capacity, and corruption within the Ministry of Commerce. This has made it difficult for Cambodian products to access overseas markets, including the EU, South Korea, and Japan.

What are the opportunities for Canada to deepen ties with Cambodia?

Cambodia has limited economic leverage as it pursues trade negotiations with the U.S. Burdened by a significant trade surplus and lacking the purchasing power to boost its imports of U.S. goods, Cambodia finds it difficult to reduce its trade imbalance. In addition, Phnom Penh’s economy is heavily concentrated in a few sectors — such as garments and apparel — leaving it highly exposed to external shocks.

With these mounting challenges, Cambodia may find renewed impetus to further diversify its economic partnerships. As of 2024, Cambodia-Canada bilateral trade had reached about C$2.4 billion, up nearly 25 per cent from 2023. Cambodian exports to Canada are primarily apparel, including trousers, shorts, jerseys, and T-shirts. Canadian exports to Cambodia are modest, comprised mostly of vehicles and industrial machinery.

However, beyond expanding trade, there are opportunities to support Cambodia’s development priorities, which align with Canada’s strengths. For example, Canadian know-how in sustainable agriculture and agri-tech could support Cambodia's efforts to modernize its rice and cassava sectors while meeting international quality standards. The renewable energy sector is another promising opportunity, given Cambodia's growing energy needs and Canada's strengths in hydropower and solar technology. Ongoing talks for a Canada-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement offer a structured platform for closer co-operation in these areas.

Yet the extent to which Cambodia can deepen ties with Western partners, including Canada, will depend on how it manages its strategic proximity to Beijing. While Cambodian officials are aware of the risks of overreliance on China, they continue to pursue a strategy of diplomatic hedging — seeking economic diversification without alienating a key benefactor.

• Edited by Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, and Ted Fraser, Senior Editor, APF Canada