The Takeaway

Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s national “food estate” program — launched in 2020 to ward off an “impending” global food security crisis — is failing, according to recent investigations by independent environmental researchers. The well-intentioned program has produced disappointing results, failing to increase the production of important staple crops like rice. The program, in its third year of implementation, continues even as environmental groups and experts decry its damaging environmental and social impacts.

In Brief

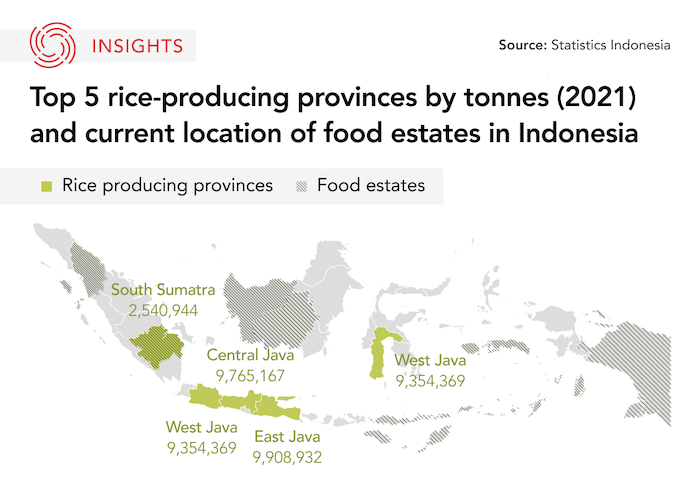

Heeding the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s warnings of an “imminent” global food crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic (and in response to pandemic-induced food supply disruptions and shortages in Indonesia), Widodo initiated his food estate program in 2020, tasking the Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing, the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Ministry of Defense to manage it. Due to its perceived importance, the central government designated the program a “national strategic project” for 2020-24. The program aimed to enhance domestic food security by reducing Indonesia’s dependence on rice imports, improving the country’s food distribution system by creating rice centres (outside of the major rice-producing region of Java), and increasing domestic food production.

The plan included developing vast farmlands, or “food estates,” to grow crops like rice, cassava, potato, garlic, and shallots in the provinces of Central Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, North Sumatra, South Sumatra, East Nusa Tenggara, Papua, and Maluku.

Implications

Widodo’s “food estate” program is not new in Indonesia. In fact, it is similar to the “Mega Rice” project initiated by former president Suharto in 1996, which aimed to transform one million hectares of peatland into rice paddies in Central Kalimantan. The project was deemed a failure in the late 1990s, and the land was abandoned by the subsequent government. Widodo argued that his program would improve infrastructure like irrigation systems and avoid the mistakes of the Mega Rice project. Ironically, some of the same land in Central Kalimantan used for the Mega Rice project is now being used by Widodo’s government for its food estate program.

Evidence from recent field investigations by independent researchers and NGOs shows past mistakes are cropping up again. For example, in the Tewai Baru food estate, located in Gunung Mas Regency, Central Kalimantan, cassava plantations produced subpar yields, leading the government to abandon the site. Residents, who have criticized the lack of thorough environmental assessments and public consultation, say the soil is unsuitable for cassava. What’s more, the government’s clearing of forest land for the plantation has worsened flooding and soil erosion, forcing local Indigenous farmers to alter their farming practices. Food estates growing rice in Kapuas and Pulang Pisau regencies have also stalled due to inadequate government support for farmers.

The Ministry of Agriculture manages the rice-focused food estates and recognizes the shortcomings of the program, while the Ministry of Defense, which manages the cassava plantation in Gunung Mas Regency, has attributed its failures to a lack of funds and the absence of any regulatory framework. The Audit Board of Indonesia (BPK) audited the program and found it to be poorly planned and conducted with inaccurate data. The project, BPK says, failed to incorporate sustainable agricultural practices and the site selection process for the program broke existing government regulations.

Undeterred by these failures and criticisms, the government continues to expand the program. Widodo’s government recently started construction on a food estate site in Maluku and greenlit a 10,000-hectare corn food estate in eastern Papua. The latter is set to be completed by 2024.

Indonesia ranked 63rd out of 113 countries in the 2022 Global Food Security Index. The country fared well in certain metrics, such as “affordability,” but performed poorly in “sustainability and adaption,” ranking 83rd in that category. The poor ranking is attributed to the lack of research and development in the sector and the lack of political commitment to adaptation strategies.

What’s Next

- Government considering another round of rice importation

The Indonesian government is considering importing 500,000 tonnes of rice in 2023 to augment its national stockpile. In 2022, the country imported the same quantity from various suppliers. Even with current importation considerations, this amount may not ensure adequate supply in the country, as Indonesia’s stockpile is supposed to hold, at minimum, 1.2 million tonnes of rice.

- Future of the project with China

After a recent visit to Beijing, Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, announced that China’s National Development and Reform Commission and China’s Ministry of Science and Technology will be supporting the food estate program by developing herbal centres and laboratories capable of genomic development of seeds, which would allow Indonesia to develop seeds domestically.

• Produced by CAST's Southeast Asia team: Stephanie Lee (Program Manager); Alberto Iskandar (Analyst); Saima Islam (Analyst); and Tim Siao (Analyst).