Free trade agreements (FTAs) have not traditionally addressed inclusivity issues pertaining to specific groups such as Indigenous peoples. Tensions remain between liberalizing trade and Indigenous inclusivity. A key reason is that international trade and investment policy and law, human rights law, and Indigenous rights and law have developed as separate fields for both practitioners and academics, giving the impression that they are unrelated.

But over the last ten years or so there has been an increase of practitioners, Indigenous businesses, organizations and individuals, and national governments working to address Indigenous rights and related issues within trade agreements.

For example, New Zealand now includes in its new FTAs a Treaty of Waitangi exclusion, which enables the government to take actions in its obligations to Māori under the treaty that may be inconstant with an FTA. And the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) includes protections for Indigenous rights. Meanwhile, the Comprehensive & Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the focus herein, includes a general reference to Indigenous peoples in the preamble, and there is specific, yet limited, mention of Indigenous groups in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand in other parts of the agreement.

– CPTPP Preamble

Mention of Indigenous rights in the CPTPP preamble is significant even though it is not binding. The preamble sets the tone and spirit for the implementation of the agreement and provides increased space for the pursuit of equitable, fair, and inclusive trade. And even though trade agreements take years to negotiate, a completed agreement is not an end in itself – it needs to be applied in practice. The real work of trade agreements, and judging and measuring success and impact, comes in the implementation. As such, the preamble’s inclusion of inclusivity and Indigenous rights offers food for thought about what this means and could mean in practice and what Canada’s role might be in advancing such inclusivity.

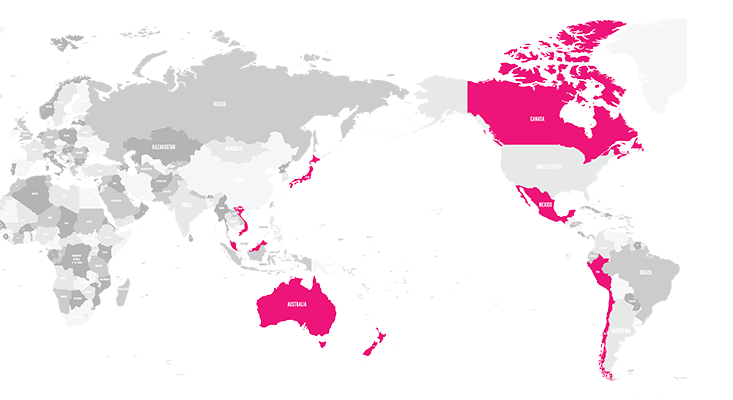

The 11-member-strong CPTPP, which came into force in 2018 for six of its members, including Canada, will be the third-largest multilateral trade area by gross domestic product once fully implemented. The member economies (Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam) represent vastly diverse cultures, languages, and histories. This includes Indigenous/minority communities with an estimated population of more than 50 million within CPTPP member states, for which there is inconsistent or incomplete data on their economies.

Currently, the degree of inclusion and recognition of Indigenous people and their rights varies significantly across CPTPP members, especially when they pertain to business development and international trade. But this diversity presents an opportunity for member states and Indigenous communities to work together further to leverage the CPTPP to increase inclusivity, limit potential pitfalls of liberalizing international trade and investment, and benefit Indigenous businesses and communities.

This analysis of Indigenous international economic participation and general situations in Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Chile, and Malaysia aims to capture some of the economic, rights and laws, and cultural diversity within CPTPP members. Including a representative of each CPTPP region (Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Pacific), these countries represent advanced and developing economies, have a variety of types of Indigenous-related laws and treaties, varying degrees of state recognition of Indigenous peoples, and diverse Indigenous economies.

– John Borrows quoted in Indigenous Peoples and International Trade

Indigenous rights and economic participation

Weak legal frameworks for protecting Indigenous rights in many parts of the Asia Pacific create challenges in recognizing and upholding rights and improving Indigenous populations' economic participation and well-being. Experts on Indigenous economic development and well-being have argued for the need for a three-part framework for overcoming these challenges in the region. This includes:

- The right to self-determination.

- The right to be recognized as distinct peoples.

- The right to free, prior, and informed consent to include Indigenous people in economic development and strengthen Indigenous rights regimes.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), which all CPTPP member states have signed, also deals with economic rights. For example, Article 3 states that, "Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right, they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development." And Article 32 speaks to the right for Indigenous peoples to develop their own priorities for development and for states to work with Indigenous peoples in good faith on projects that may affect them.

These protections can be interpreted to include the right to be included in the decision-making processes of trade agreements that could affect Indigenous peoples, lands, traditional knowledge, or property. A 2016 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples found that Indigenous peoples are disproportionately negatively impacted by the current global FTA regime as projects under FTAs often infringe on Indigenous’ rights and land. Some critics have stated that the CPTPP currently does not meet the standard of Indigenous inclusion and rights protection set out by international documents such as UNDRIP, the Sustainable Development Goals, and Special Rapporteur’s reports, or domestic laws and acts that address Indigenous rights or economic inclusion.

A contentious element in FTAs for many Indigenous peoples has been the investor-state dispute (ISDS) settlement mechanism. ISDS is an instrument that allows foreign investors to resolve disputes with the government of the host country of their investment when they feel their rights as an investor have been violated through a neutral forum seeking binding international arbitration. Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics, lawyers, and pundits have expressed concern that ISDS allows investors to make a claim for the mere loss of opportunities that might occur when a state protects or advances Indigenous rights.

Reports by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2015 and 2016 were critical of ISDS, stating that it gives investors an unfair advantage and may overrule domestic rights and protections. As Anishinaabe/Ojibwe academic and jurist John Borrows points out, states may choose not to take action to protect Indigenous rights to avoid liability, putting investor interests and Indigenous rights in direct competition. For example, an examination of Chapter 11 disputes under NAFTA found that states have won in cases where Indigenous rights were also at stake. Regardless, such findings may not be predictive of future outcomes, as arbitration results may be predicated on a specific FTA and the governments involved. The CUSMA – the new NAFTA – will phase out the ISDS system within three years. The CPTPP, however, does include ISDS. How ISDS will impact Indigenous rights under the CPTPP is yet to be seen.

Canada

Canada led the effort in amending the CPTPP to include the "Comprehensive and Progressive" title, amendments, and preamble to the agreement. Some of the modifications include greater protection for intellectual property rights, a broader scope of protection for governments from ISDS, and a preamble emphasizing inclusive values such as the importance of environmental and Indigenous rights.

International trade law practitioner Risa Schwartz has pointed out that Indigenous peoples in Canada have advocated for greater inclusion and recognition in FTAs since the late 1980s. More recently, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) has passed three resolutions since 2017 related to international trade including, (1) a First Nations Treaty Strategy, (2) developing a committee to advise Canada on First Nations’ inherent treaty rights to trade, and (3) guiding the AFN in realizing the benefits that flow from international trade for First Nations. Also, in 2017, the Inter-Tribal Trade and Investment Organization (IITIO), comprising Indigenous peoples from both Canada and the United States, drafted a submission to Global Affairs Canada (GAC) recommending the inclusion of a trade and Indigenous peoples chapter in what would ultimately become the CUSMA.

The AFN’s and others’ work over the years, and IITIO’s discussions with GAC helped the Canadian government advance its inclusive trade agenda and push for an Indigenous chapter in CUSMA. Although the Trump Administration’s pushback meant that an Indigenous chapter was not ultimately included in CUSMA, Schwartz argues that one significant development was the inclusion of an Indigenous Peoples Rights exception. This exception, which states that the "Agreement does not preclude a Party from adopting or maintaining a measure it deems necessary to fulfill its legal obligations to indigenous peoples," helps reduce potential state concerns of potentially being caught between its obligations to Indigenous peoples and investors’ rights under the agreement.

– The Constitution Act, 1982, Section 35

The Canadian Government states that CPTPP does not supersede Canada's obligations to Indigenous peoples under Section 35 of the Constitution. The CPTPP also includes a chapter that acknowledges the importance of traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples; however, Schwartz points out that it is unclear how these statements will protect and support Indigenous peoples in practice. There are also exceptions for Canada that benefit Indigenous peoples concerning procurement and trade.

Canada has an additional joint declaration with New Zealand and Chile, affirming its commitment to a progressive trade agenda, including protecting and inclusion of Indigenous peoples and rights. However, unlike under CUSMA, there is no broad exception for states to fulfill their obligation to Indigenous peoples without fear of repercussion. Under CPTPP, an investor can still sue a state under an ISDS for damages. This leaves open the potential for states to pay hefty damages to companies even if they were exercising their constitutional duty to protect Indigenous rights.

New Zealand

New Zealand has sought to protect Māori interests and fulfill its obligations to Māori under the Treaty of Waitangi by negotiating a ‘Treaty of Waitangi’ exception into its FTAs. In New Zealand constitutional law, under the Treaty of Waitangi the government has certain obligations to protect Māori interests in their lands, resources, culture, and political interests. The Waitangi exception is the only explicit, specific exception related to Indigenous rights incorporated into the CPTPP. The Waitangi exception, which has become common in New Zealand agreements, first appeared in 2000 in its FTA with Singapore.

According to the Government of New Zealand, the exception allows it to adopt any policy it considers necessary to fulfil its obligations to Māori. However, pundits have noted that the exception does not go far enough in protecting Māori rights and that Māori did not help co-develop with the government the original exception meaning that it may not fully represent Māori views, values, and interests . Other concerns have arisen regarding the ambiguity of the exception and problems in its interpretation. During the CPTPP negotiation process, a ruling by the Waitangi Tribunal, a permanent commission that "makes recommendations on claims brought by Māori relating to legislation, policies, actions or omissions of the Crown that are alleged to breach the promises made in the Treaty of Waitangi," found that although the government's interpretation of the exception is reductionist, it was sufficient enough to protect Māori interests. A particular area of concern for Māori is investor claims under CPTPP through ISDS, as some of the wording in the Treaty of Waitangi exception makes it unclear whether the exception applies to those claims.

New Zealand is also part of the additional statement in the CPTPP with Canada and Chile reaffirming their commitment to a progressive trade agenda, which encompasses Indigenous rights. Te Taumata, a key Māori partner for the government, is helping ensure that Māori views, interests, and principles are included in all of New Zealand’s trade negotiations and related policy development.

Chile

There are nine Indigenous groups in Chile, with a total population of 2.2 million people and representing 12 per cent of the Chilean population. The largest Indigenous group is the Mapuche, representing about 90 per cent of the country's Indigenous population. Despite this large population, Chile does not recognize Indigenous rights in its constitution – the only country in Latin America that does not. Nonetheless, Chile adopted the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 (Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989) in 2008, a major binding international convention that protects Indigenous rights and a forerunner to UNDRIP.

There have been increased protests by Mapuche and other groups since the 1990s against multinational companies conducting business in Chile, mainly in resource sectors on ancestral lands. Perhaps one of the most notable cases concerning Indigenous rights in Chile was between the Indigenous Aymara and Atacama groups and a water bottling company that wanted to extract water from their ancestral lands. In 2009, the Chilean Supreme Court upheld that under the ILO convention, which Chile had adopted the year prior, the communities' right to exploit the water preceded the rights later granted to the company to extract it. It also found that Chile’s 1993 Indigenous Law (Law 19.253) recognizes Indigenous rights over the water and guarantees their right to register that claim.

Chile is also party to the Joint Declaration in the CPTPP with Canada and New Zealand that emphasizes a progressive trade agenda and the protection of Indigenous rights. Without an Indigenous chapter or explicit Chilean Indigenous exception clauses in the CPTPP, and with the absence of constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights in the Chilean Constitution, it is difficult to determine if Indigenous rights would be protected in an ISDS dispute under the CPTPP.

Japan

According to government surveys, the Ainu, an Indigenous group in Japan, has a population of about 20,000 people. But due to survey methodologies and the fact many members hide their identity due to ongoing discrimination and legacies of colonial trauma, actual estimates put that figure at closer to 100,000. Much like colonial experiences in the West, the last 150 years have seen the Japanese state encroach upon Ainu lands and make efforts to limit Ainu culture, language, and ways of life. The rights of Ainu in Japan and their legal protection have been slowly evolving since the mid-1990s. Although a Japanese court first recognized the Ainu as Indigenous in 1997, the Japanese Diet didn't follow suit until 2008, a few months before Japan hosted the G8.

The first legislation to recognize the Ainu as Indigenous came in 2019 with the Ainu Policy Promotion Act. Like the 1997 Ainu Cultural Promotion Act that preceded it, this new law makes further headway in protecting and promoting Ainu culture. For example, part of the new law includes opening a cultural museum and park, recognizing the Ainu's culture and contribution to Japan, and other tourism-related supports. Still, this new law still does not address political, land, or economic rights. The first lawsuit by the Ainu to confirm their rights under the Act was filed in August 2020 in a dispute to affirm Ainu ancestral fishing rights, which the government does not currently recognize. Since these developments have focused on domestic circumstances and interpretations of rights within the Japanese constitution, it leaves legal questions and uncertainty around the protection of Ainu rights if a foreign entity under the CPTPP were to infringe upon them.

Malaysia

Indigenous peoples in Malaysia collectively number about 4.3 million people, or 13.8 per cent of Malaysia's population. In 2007, Malaysia officially adopted UNDRIP; however, much of Indigenous rights in Malaysia are derived from colonial-era statutes, such as the federal Aboriginal Peoples Act of 1954 (revised in 1974). Collectively known as the Orang Asli, the Indigenous people of peninsular Malaysia have some protection under the Act, which defines their legal status and some land rights where the state can designate areas as Indigenous land reserves. And yet, these protections can be weak as Orang Asli cannot obtain title to land nor do they enjoy security of tenure as the state can repeal reserve status at any time without consultation.

There has, however, been some affirmation of Indigenous title in Malaysian common law. A 1997 Malaysian High Court decision affirmed Orang Asli rights to Indigenous title and to live and use traditional lands as their ancestors did. This recognition of native title has the potential to halt any resource development on Indigenous lands through the courts. However, the Malaysian Government has continued to oppose the recognition of Indigenous title and thus risks legal consequences. At the same time, the government also has the option of quashing native title recognition through legislation.

Domestic groups and international non-governmental organizations have repeatedly criticized the government for its continued unequal treatment of Orang Asli and its prioritization of investment and resource development, often to the detriment of these people. In 2019, the Malaysian Government committed to strengthening Indigenous rights in Malaysia and, in an unprecedented move, sued the state government of Kelantan for infringing on Indigenous rights by handing out permits for resource extraction on ancestral lands. With a weak legal rights framework for Indigenous rights in Malaysia, it is uncertain what kind of protection would be afforded to such rights under a CPTPP investment or dispute.

The future of Indigenous international trade

There is a diversity of frameworks and legal recognition of Indigenous rights and title across the member states of the CPTPP, and that diversity extends throughout the Asia Pacific. Nonetheless, the CPTPP preamble, which reaffirms the importance of Indigenous rights, inclusive trade, and traditional knowledge, sets a positive tone for the future implementation of the CPTPP, Asia Pacific-Canada trade and investment in general and specifically for Indigenous international trade, and other FTA developments. After all, the population of Indigenous people in the Asia Pacific is significant, with 333 million, accounting for about 70 per cent of the world's Indigenous population.

We finish by highlighting three, but certainly not the only, areas of importance for continuing Indigenous inclusivity in international trade and investment. First is the need for continued, and in many cases new, Indigenous-led, co-created international trade policy with federal/central governments and among Indigenous peoples. While there was likely no Indigenous participation in the CPTPP negotiations, Indigenous individuals and organizations in Canada provided direct input into the CUSMA, and Māori are actively engaged with the New Zealand government on current trade policy. This is a positive sign of things to come for inclusivity in international trade policy.

Second, we are likely to see an increase in Indigenous-led domestic and international programs supporting Indigenous international trade. While trade agreements, like the CPTPP, set rules and standards, the hands-on work begins with the implementation of these mechanisms. Many broad initiatives currently underway could prove successful for maximizing the benefits of FTAs for Indigenous businesses. ‘Inter-national’ trade – that is, trade facilitated by and among Indigenous businesses and nations in different countries, such as between Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and Taiwan – is at various developmental stages. The facilitators of efforts like INDIGI-X and the World Indigenous Business Forum also point to the value for further connecting Indigenous professionals in Canada and the rest of the world to sustain and build such trade. These initiatives enable the fine-tuning of programs and support systems that help Indigenous businesses and entrepreneurs become further involved in international trade on their own terms. CPTPP members could further support such Indigenous-led initiatives to build networks of Indigenous businesses and professionals within the trade bloc. Supporting inclusivity in trade contributes to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development's goal of "leaving no one behind," and thus, Indigenous and national economic well-being.

Third, there is an urgent need for data on Indigenous economies within CPTPP members (and beyond). Research based on sound data should be the backbone of trade policy and subsequent programs and supports. And yet, it is strikingly noticeable that quality, up-to-date, and comparable data on Indigenous economies (and populations) within CPTPP member economies is lacking, not tracked, or not publicly available. Canada, Australia and New Zealand appear to have the best available data and are at the forefront in this area. For example, the Canada Council for Aboriginal Business initiated its own economic and business-data related projects and it has collaborated with the Government of Canada on research on the size and shape of the Indigenous economy, including the number of entrepreneurs and/or small and medium enterprises (SMEs), sectors, and the number of exporters. And an updated study will likely take place in 2021. But as with data from Australia and New Zealand, there are important caveats to Canada’s data (i.e. sample size of surveys, outdated) and it is difficult to compare across international jurisdictions as research methodologies and data collected in domestic surveys and studies often differ in each economy.

International bodies such as the International Labour Organization and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have begun to work on some of these issues. Last year, the OECD called for Indigenous people and governments to work together in "improving Indigenous statistics and data governance" as one of its four recommendations to "strengthen the enabling environment for Indigenous economies." And the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) has called for the economic, financial, and social inclusion of Indigenous people for years. With New Zealand in line to host APEC in 2021 with significant Māori participation, we may see further development of data-related initiatives. As a member of these three organizations, Canada could ensure that it devotes adequate resources to work with Indigenous peoples and organizations on these matters domestically and internationally through these multilateral organizations.

With research assistance from Quinton Huang, Junior Research Scholar-Engaging Asia, APF Canada.

The authors would like to thank James (Sakej) Youngblood Henderson, Risa Schwartz, Rick Colbourne, Aref Amanat, Raylene Whitford, Chris Karamea Insley, and Nicole Gombay for sharing insights and stories that helped shape this piece.