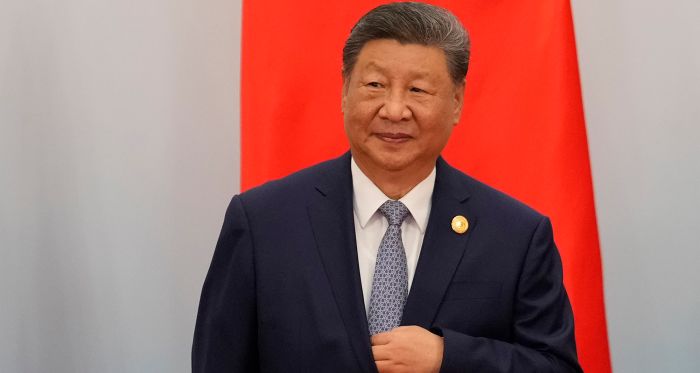

In his New Year address, Chinese President Xi Jinping lauded the fact that China’s economy has reached “a new milestone,” with its 2025 GDP poised to total 140 trillion Chinese yuan (C$27.86 trillion). Xi added that the country’s “economic, scientific, technological, defence, and overall national strength have reached new heights.”

Xi’s confidence and optimism were striking. While New Year speeches are typically upbeat, this year’s address sounded noticeably more assured than last year’s, when external and domestic challenges featured more prominently.

Coupled with signals from key Communist Party of China (CPC) economic planning meetings in recent months, the leadership appears generally satisfied with the current trajectory of the economy and sees little need to change course in 2026 — or possibly beyond.

China’s economic strategy is therefore likely to remain largely consistent, with continued emphasis on technology- and innovation-driven growth, strengthening advanced manufacturing, and a moderate expansion of consumption.

At the same time, policymakers are expected to further pursue industrial deregulation and improve regional co-ordination of industrial output, while expanding trade and inbound investment as tools to manage heightened global economic volatility.

The 15th ‘Five-Year Plan’: continuity over change

In 2026, China will unveil its next Five-Year Plan (FYP), setting the blueprint for economic and social development over the next half-decade. The Chinese economy continues to face significant structural challenges, including industrial overcapacity, low corporate profitability, a gloomy property market, and mounting local government debt.

Yet China has shown notable resilience, maintaining growth that has defied many expectations. Some analysts now suggest that both the property market and local government debt levels could stabilize or even gradually improve in 2026.

While full details of the plan will not be unveiled until the National People’s Congress meets in March, key signals have already emerged from the CPC’s Fourth Plenum in October 2025 and the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2025.

Official readouts suggest that Beijing believes China has largely weathered the shock of a rapidly changing global trading system and performed better than anticipated despite intense trade tensions with the U.S. and, to a lesser extent, with other developed and emerging economies. China remains on track to meet its five per cent growth target for 2025, although momentum has slowed: third-quarter GDP growth dipped to 4.8 per cent, Purchasing Managers’ Index readings have improved modestly, but retail sales and housing activity remain weak.

Rebalancing consumption and (over)production

“Boosting domestic consumption” appears frequently in post-meeting communiqués. Policymakers have vowed to support higher consumer spending on goods, and more importantly, on services including home support, senior care, and nursery care. However, beyond an expanded consumer trade-in program, which reportedly attracted over 350 million participants last year, concrete fiscal measures remain limited.

Notably absent are large-scale commitments to pension reform, particularly in rural areas, as well as expanded government spending on healthcare, elder care, and education — reforms that could deliver an immediate boost to household consumption.

While consumption has grown roughly in line with GDP over the past several years, household consumption still accounts for only around 40 per cent of GDP in China, far below the global average of about 60 per cent. With household savings rates near 32 per cent of disposable income, the government has ample policy space to unlock consumer demand but remains reluctant to do so.

This reluctance reflects a deeply entrenched belief among policymakers that prosperity is achieved through production and increased productivity, not consumption. Higher productivity, greater industrial output, and the resulting tax revenue are viewed as the primary solutions to many economic and social problems faced by China.

Beijing continues to emphasize the supply side of the economy, deploying technology-driven “new productive forces” to produce higher quality products more efficiently. The goal is to boost company profits, raise wages, ease local government debt, and expand fiscal capacity, eventually enabling greater social spending. In this framework, expanding the economic “pie” takes precedence over near-term fiscal redistribution.

Tackling “involution”

Chinese economic planners have acknowledged the problem of “involution” — excessive competition that drives down profits — particularly in sectors such as electric vehicles, solar panels, and batteries. Efforts to curb price wars through reduced subsidies and administrative guidance, however, have had limited success.

Going forward, Beijing plans to intensify efforts to rein in oversupply by promoting ‘consolidation,’ meaning fewer producers, higher value-added output, and stronger national champions. The central government has also pledged to better co-ordinate industrial policy nationwide, discourage destructive regional competition, and encourage development “adapted to local conditions.”

However, without reform to local government revenue structures — which continue to incentivize production and exports — a rapid resolution of overcapacity remains unlikely. As a result, trade frictions with both advanced and emerging economies could intensify.

Shifting growth drivers: from property to innovation

From January to November 2025, new home sales in China fell by over 11 per cent year-on-year, while real estate investment declined by nearly 16 per cent, according to official data. The sharp downturn of the Chinese property market since 2022 and a sizable plunge in the overall housing value are often cited as signs of trouble in the Chinese economy.

Yet this contraction reflects a deliberate policy choice. Beijing aims to reduce the property sector’s outsized role — previously estimated at 25–30 per cent of GDP — and redirect capital toward advanced manufacturing and high-tech industries. This shift fuelled a strong rally in technology and AI-related stocks last year.

Looking ahead to 2026, China is expected to further prioritize AI, quantum technology, bio-manufacturing, hydrogen energy, nuclear fusion, and related frontier technologies. While innovation-driven growth remains modest, estimated at roughly 15 per cent of GDP in 2024 according to Bloomberg, leaders see it as the primary engine of “high-quality growth.” Whether it can quickly offset the drag from the shrinking property sector, however, remains unclear.

Managing a “complex external environment”

Despite ongoing tensions with the U.S., China’s overall trade surplus exceeded US$1 trillion in the first 11 months of 2025, driven largely by exports to non-U.S. markets. The one-year tariff truce with the U.S. has provided short-term stability, which Beijing is using to strengthen resilience ahead of future rounds of negotiations.

The tariff war has prompted China, like many countries, to turn inward and expand international trade ties — pursuing deregulation at home while accelerating market diversification away from the U.S. The upcoming FYP is expected to emphasize the need for “sustained efforts” to build a “unified national market,” aimed at reducing regulatory barriers across jurisdictions and improving the flow of capital, resources, and labour.

At the same time, Beijing is doubling down on its push for self-reliance — not only in “indigenous advanced technologies,” but also by leveraging the untapped potential of its “massive domestic market.” This approach reaffirms the “dual circulation” strategy first introduced in the 14th FYP in 2020, which seeks to strengthen domestic demand while maintaining international trade.

Preserving full supply chains and a comprehensive industrial base across all sectors remains a core pillar of China’s economic strategy, leaving little appetite to cede industrial capacity in order to reduce manufacturing output.

That said, officials have reiterated commitments to inbound trade and investment and have identified “balanced trade” as a long-term policy goal. Targeted measures in the 15th FYP are expected to expand imports of high-quality goods and services and open additional sectors wider — including telecommunications and biotechnology — to foreign investors. However, amid persistent growth pressures and the absence of a clear implementation timeline, doubts remain over how determined Beijing is to meaningfully reduce its trade surplus.

Implications for Canada-China economic relations

In an era marked by growing uncertainty and increasingly unilateral actions by Donald Trump’s administration to assert American primacy, Beijing is striving to position itself as a more reliable and responsible global power, one that upholds the international trading system and respects the broader international order.

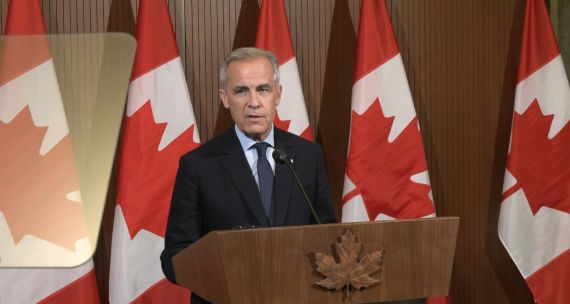

China has intensified its diplomatic outreach, with Xi recently hosting leaders from France, Ireland, and South Korea, and with upcoming engagements expected with Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz.

Despite continued wariness over China’s intentions and its expanding economic and strategic influence, many countries are increasingly hedging between Washington and Beijing — a dynamic Beijing hopes will ultimately tilt in its favour.

With the forceful removal of Nicolás Maduro followed by Trump’s announcement to “run” Venezuela, Washington is asserting control over the country’s massive oil reserves indefinitely.

This has significant implications for the global energy landscape and for Canadian oil exports. If Venezuelan crude is redirected to U.S. Gulf Coast refineries once sanctions ease, it could displace heavy crude imports traditionally sourced from Canada. Such a shift would increase the urgency for Canada to diversify its energy export markets, particularly by expanding access to Asian markets via the West Coast, where China — historically a leading buyer of Venezuelan crude — remains a key destination for Canadian heavy oil.

Carney’s visit to China is widely expected to focus on trade. Potential areas of progress include easing frictions on agricultural trade, while a broader range of Canadian industries could potentially benefit from Beijing’s stated commitment to boosting domestic consumption and expanding imports of goods and services under the next FYP.

Energy co-operation will also be a focal point, as China seeks to secure reliable supplies of conventional energy and Canada looks to expand and diversify its export markets. Recent developments in Venezuela have added further urgency to these discussions.

• Edited by Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, and Ted Fraser, Senior Editor, APF Canada