On February 8, Thais voted in a snap parliamentary election. Defying the predictions of most polls, the conservative Bhumjaithai Party (BJT), led by incumbent Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul, won with 193 out of 500 House of Representatives seats. The progressive People’s Party, which had been predicted to win, finished in a distant second, with 118 seats. Pheu Thai, the once dominant populist party associated with former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra and his family, had its poorest performance ever, with 74 seats.

While early post-election analyses are suggesting that the results of the vote signal a return to stability after years of political turbulence, several near- and medium-term developments could complicate matters. For example, with BJT falling short of the 251 seats needed for a majority, coalition talks with smaller parties, and potentially Pheu Thai, are expected to take place in earnest over the next few weeks. However, a large volume of complaints from voters over election irregularities in several provinces has prompted the People’s Party and Pheu Thai to demand recounts. Investigations could delay the formation of a government.

In addition, upcoming court decisions could have a destabilizing effect. On February 9, the day after the election, the National Anti-Corruption Commission ruled that 44 members of the now-defunct Move Forward Party — the People’s Party predecessor — committed serious ethical breaches when they proposed amending the country’s lèse-majesté (“royal insult”) law in 2021. The country’s supreme court will decide within the next month whether those 44 members, including Move Forward’s leader, Pita Limjaroenrat, and the People’s Party leader, Natthaphong Ruengpanyawut, will face further restrictions on their future political activities, a decision that would likely incense their supporters.

Finally, debates over a redrafting of the country’s constitution will likely expose major political differences in what remains an ideologically divided country. On the same day as the general election, voters also cast ballots in the first round of a referendum on whether to begin writing a new charter to replace the 2017 constitution implemented during the most recent period of military rule (2014–19). With 65 per cent of voters supporting a constitutional rewrite, the process will now head back to parliament to select the drafting committee. The committee’s proposal will be voted upon by Thai citizens in a future referendum.

The return of electoral conservatism

The pattern for Thailand’s past seven general elections (2005, 2006, 2007, 2011, 2014, 2019, and 2023) was that the winning party challenged, or at least was perceived as challenging, the interests of Thailand’s royalist establishment — its monopolistic businesses, elements of the civil service, the military’s upper-echelon, and the palace. In response, unelected actors, especially from the military and various commissions and courts, interfered in the democratic process, hindering the winning party’s ability to form government or complete its full four-year mandate. This pattern has been described as “the cycle.”

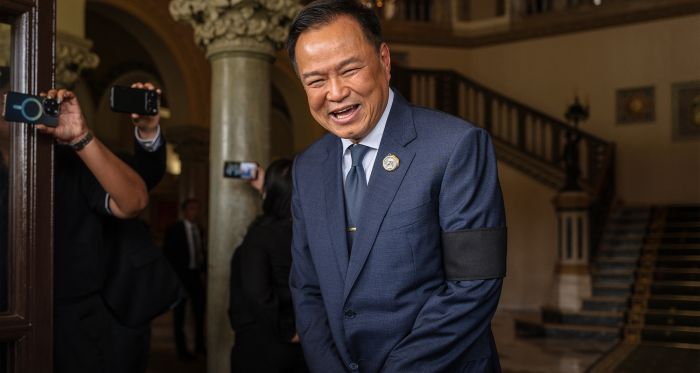

In the most recent election, supporters of the People’s Party had hoped that a clear electoral mandate would make it harder for unelected actors to undercut it, thereby breaking the cycle. However, with BJT’s win, the cycle has likely been paused. Anutin and BJT have a much stronger chance of being able to complete a full parliamentary term. As a conservative party that is close to traditional business interests, has backed the military, and is thought to have the support of the palace, it is very likely that unelected actors will leave Anutin and the party untouched.

The results of the February 8 election can be seen as part of a larger global trend of a ‘flight to safety’ in an increasingly fragmented, unpredictable, and insecure world. In Thailand, the sense of insecurity and fragmentation were exacerbated by the still-simmering 2025 border dispute and military conflict with Cambodia. The conflict, which has killed at least 100 soldiers and civilians on both sides and is seen by both governments as a matter of self-defence against an aggressor, has resulted in a rally-around-the-flag effect. In Thailand, nationalist messages and imagery circulated widely on social media and found their way into the election campaign, with Anutin’s BJT positioning itself as the flagbearer of the country’s integrity and national security. The rise in nationalist sentiment made it difficult for the People’s Party to recapture its progressive support base and middle-ground voters who were concerned about perceived threats to sovereignty and the country’s national standing.

While previous versions of Thailand’s progressive parties (the Future Forward and Move Forward parties) were more critical of the militarization of Thai politics and society, the People’s Party moderated its message, distinguishing between generals with a history of seizing power in coups and ordinary frontline soldiers. This reframing, along with several other shifts — including backtracking on its support for revising the lèse-majesté law, moving away from its social movement origins, and voting for Anutin to become prime minister in exchange for an early election and a referendum on drafting a new constitution — drew the ire of its more grassroots and reform-oriented supporters.

Nevertheless, the People’s Party clearly gambled that it was doing what was necessary not only to try to win the 2026 election, but also to implement its reform agenda by being able to take and hold onto power for the duration of a parliamentary term. Instead, it now finds itself not only back on the opposition benches, but also still facing legal threats.

Analyses of the People’s Party election loss are likely to focus on the effect of Pita’s 10-year ban from politics. From his first day as party leader, Natthaphong, the current leader of the People’s Party, has been compared unfavourably to both Pita and former Future Forward leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit in terms of charisma and popular appeal. However, there are also other significant differences between what has transpired in 2026 and the recent past. For example, the lead-up to Move Forward’s first-place finish in 2023 was marked by the presence of a large-scale social movement that pushed back against Thailand’s elite establishment and demanded change. There was no such wind-in-the-sails effect for the People’s Party. Instead, the 2026 election was less of a clash between a reform movement and the establishment than a typical electoral battle between relatively well-institutionalized political parties.

Furthermore, BJT, in contrast to the junta and military-backed parties of the recent past, presented itself as a more moderate proxy for Thailand’s conservative establishment. While BJT is sincere about defending nation, religion, and king, it has historically been pragmatic in policymaking, its spearheading of the decriminalization of cannabis in 2022 as one example. The party also took a page out of Thaksin’s populist playbook by implementing a government co-payment system for food and other basic needs to combat affordability issues. Its stated openness to the decentralization of political power to the provinces and a shift away from military conscription also leans into reforms championed by the People’s Party.

Notably, BJT has also been ideologically flexible when crafting political alliances. From 2000 to 2007, Anutin was a senior executive member in Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai party, which then was considered the central political threat to Thailand’s establishment. After Thailand’s Constitutional Court banned him and other party executives from politics for five years for their association with Thai Rak Thai, he became leader of BJT and helped to establish the party as a regional political powerhouse in the country’s lower northeast and, in turn, became a kingmaker for larger parties — supporting Pheu Thai in some instances and military-backed parties in others.

This openness allowed BJT to recruit members of other parties, factions, and clans — including from Pheu Thai — to strengthen its policymaking team and its network of influential local politicians and powerbrokers for electoral gain. Pheu Thai’s reputation was severely damaged after Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra was removed from office in August 2025 for seemingly siding against the Thai army in a friendly phone call with Cambodia’s long-time former leader (and current president of Cambodia’s senate), Hun Sen, during the early stages of the border conflict. BJT’s distance from the discredited military-aligned conservative parties also made it more palatable to centrist voters and provided less of a foil on which the progressive People’s Party could capitalize.

Thailand’s foreign policy and implications for Canada

Counting on domestic stability in Thai politics remains a gamble as long as significant internal divisions over the country’s identity and future direction persist. However, a longer-than-usual term as prime minister for Anutin would at least provide the policy continuity that has been missing for many years as Thailand churned through prime ministers.

Countries such as Canada can look forward to engaging with a Thailand that is more active on the world stage and, like Canada, is seeking new partners in an increasingly challenging international environment. It is a common lament in Thailand’s foreign policy circles that the country has been far too inward-looking since the cycle of elected governments being curtailed by unelected actors began with the 2006 coup that removed Thaksin from power. Since then, Thai governments, both civilian and military, have focused primarily on managing domestic crises and attempting to gain domestic support and legitimacy. Meanwhile, other Southeast Asian countries have begun to overshadow Thailand, outperforming it in growth and macroeconomic health and in playing a larger role in global political affairs.

One noticeable shift in the 2026 election campaign was that foreign policy was clearly back on the agenda, with BJT and the People’s Party acknowledging that, in a changing global order where old certainties can no longer be relied upon, it is imperative that Thailand be proactive on the world stage. Sihasak Phuangketkeow, a seasoned and respected career diplomat who became foreign minister in September 2025, is likely to continue in his role. Canada can look forward to working with him on areas of shared interest, including clean energy and finalizing the Canada–Thailand free trade agreement.

Canada, however, should engage mindfully. If Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s foreign policy doctrine takes the values-based element of values-based pragmatism seriously, it should remain attuned to the fact that Thai laws and institutions continue to be weaponized against challengers to the establishment, some of whom have found safe haven in Canada. The cycle may be paused, but it has yet to be broken.

• Edited by Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, and Ted Fraser, Senior Editor, APF Canada