Rationale & Context for the Study

In the coming months, the Government of Canada is expected to release its Indo-Pacific strategy, which will signal the intensification of its foreign policy focus on Asia and outline the contours of what engagement with the region could look like. As we await the details of the strategy, two broad points are worth noting:

- Making Asia more prominent in our international orientation will require active involvement by more than a handful of federal government ministries. As has been the case in other countries that have carried out similar strategies, sub-national governments, educational institutions, and civil society organizations also have an important role to play in this effort. So, too, do ordinary Canadians.

- The long-term success of the Indo-Pacific strategy will hinge on our ability to view our Indo-Pacific counterparts through more than the narrow lens of trade and other commercial transactions. Undoubtedly, economics will be a core component of the strategy. But, Canada’s value as an Indo-Pacific partner requires that we take a more holistic approach. As such, we will need to invest in initiatives that raise our awareness of the region’s histories, cultures, and societies. This means not treating Asia merely as an object of study but committing to gaining a deeper level of mutual understanding between us and our counterparts across the Pacific.

On both points, Québec is an intriguing case. In February 2022, the provincial government released its own Indo-Pacific strategy[1], which aims to bolster the province’s positioning in the region through trade and investment, as well as through cultural and educational initiatives. Such initiatives include setting up a university-based Asian Studies chair, extending its scientists-in-residence program to Asia, and developing new youth opportunities for internships and volunteer projects in Asia.

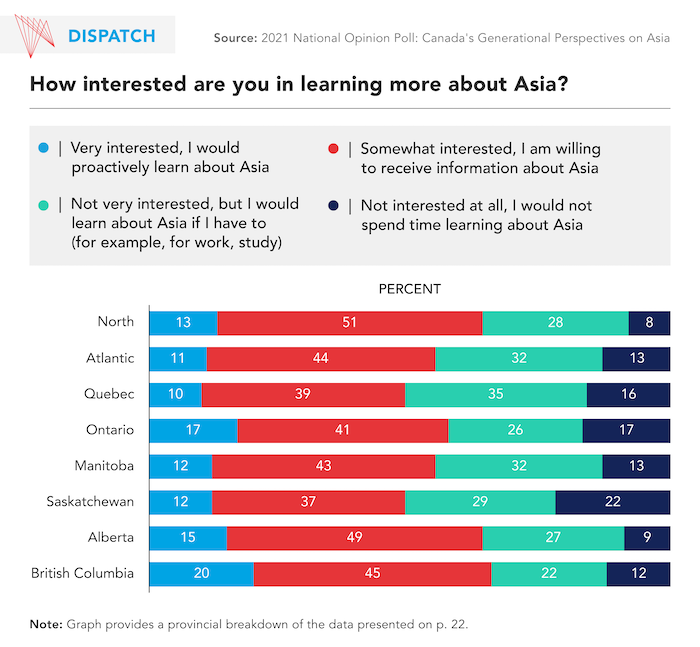

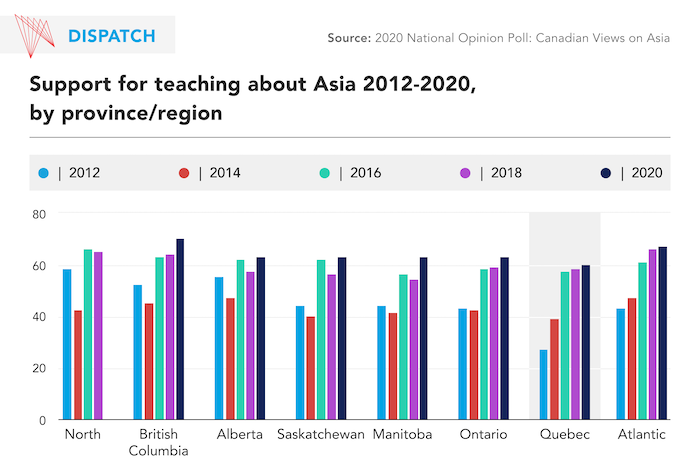

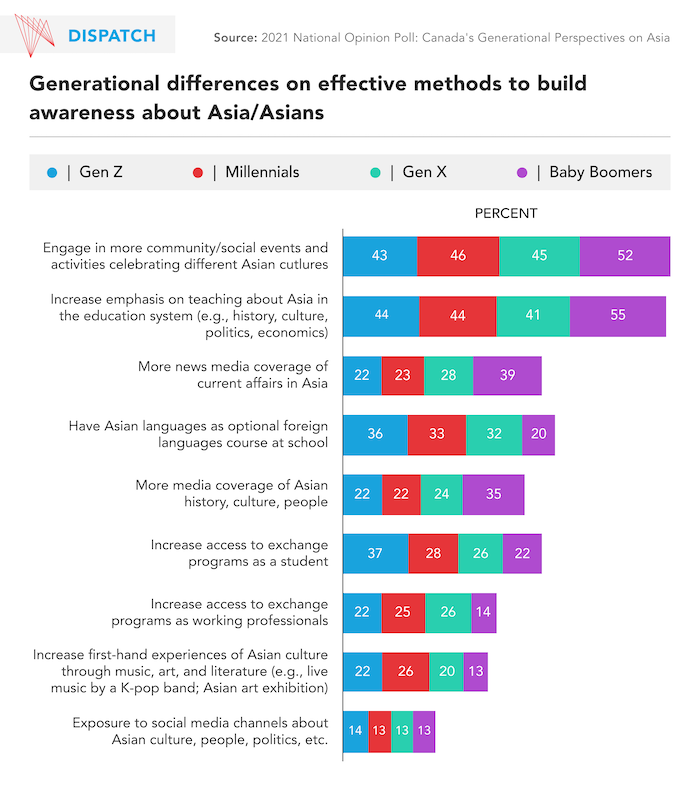

Recent polling suggests that Quebecers may be receptive to an increased focus on the Indo-Pacific. In 2021, the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s (APF Canada) National Opinion Poll asked adults in every part of the country about their interest in learning more about Asia. In Québec, the percentage who said they were “interested” was 49 per cent – 10 per cent “very interested” and 39 per cent “somewhat interested.” The total was lower than in other provinces, but interest in Asia by half the population is a solid foundation from which to promote greater engagement. Moreover, an APF Canada poll from the previous year (2020) shows impressive growth in Québec in its awareness of the importance of Asia. When asked whether there should be more emphasis on teaching about Asia in provincial schools – its geography, histories, societies, cultures, and so on – support has increased more in Québec than in any other part of Canada, more than doubling, from 27 per cent in 2012 to 60 per cent in 2020.

What about support for teaching Asian languages? In all regions of Canada, this has been more modest. But data for the same period (2012-2020) also show a clear upward trend, climbing from 25 per cent in 2012 to 41 per cent in 2020. It should be noted that in Québec, the percentage of respondents who support teaching Asian languages is still lower (37%) than those who oppose it (52%) (support was highest in B.C., at 51%, and lowest in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, at 29%). Nevertheless, the roll-out of an Indo-Pacific strategy, both provincially and federally, may impact perceptions about the need for more Asian-language speakers. Indeed, for Québec and for the rest of Canada, such a strategy would be incomplete without a commitment to the types of capabilities that will deepen our understanding of the region and demonstrate our seriousness as an international partner. Creating programs to support the acquisition of this vital skill set should take careful account of what it is that attracts people, especially youth and young adults, to want to learn Asian languages. This report explores those questions in the context of Québec.

The findings presented here are based on interviews conducted in spring 2022 with 25 young adults (aged 18-38) in Montréal who are learning either Japanese or Korean. Fourteen of them identify as Francophone, seven as Anglophone, and the remaining four as speaking a first language other than French or English. The majority of the participants were enrolled in these language courses not for university or college credit, but rather on their own initiative and based primarily on their personal interest. As such, these interviews shed valuable light on questions that will take on greater significance as Québec – and the rest of Canada – moves into a more intensely Indo-Pacific phase of its international relations. These questions include:

- What motivates young adults to learn an Asian language, and how do these motives change, if at all, over time?

- What is the connection between learning an Asian language and developing a broader awareness of the culture, history, and society with which the language is associated?

- What factors should be considered in promoting the learning of Asian languages in the context of Canada’s commitment to French-English bilingualism?

Key findings from the interviews included:

- For most participants, Japanese or Korean popular culture provided the initial spark that led them to enroll in a Japanese or Korean language class. In some cases, learners had a mixture of motives, and sometimes these motives evolved to include a desire to pursue a career somehow connected to one of these countries.

- Participants received little formal education about Japan or South Korea in their primary or secondary schooling, or in their university or college education, and few have had the opportunity to visit their country of interest. Nonetheless, many were proactive in seeking ways to learn more about the target country.

- Despite the lack of school-based education about Asia, several participants demonstrated a critical and nuanced understanding of and appreciation for Japanese and/or Korean culture and society, often at a level that would help to challenge stereotypes about these countries. They also expressed a desire for more local opportunities to interact with native speakers of these languages and learn more about their countries and cultures.

- Overall, neither the Anglophone nor Francophone participants viewed Canada’s commitment to French-English bilingualism as a major obstacle to learning Asian languages.

The insights gleaned from these interviews can help inform Canadians at different levels of government and within civil society on how to design Asian-language programs that are responsive to what motivates current and future potential learners. Such programs, in turn, will help us nurture the type of familiarity that will support new foreign policy orientations toward the Indo-Pacific by Canada and Québec.

[1] Ministère des Relations Internationales et de la Francophonie. Stratégie territoriale pour l’Indo-Pacifique. Québec : Gouvernement du Québec. 2021. https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/relations-internationales/publications-adm/politiques/STR-Strategie-IndoPacifique-Long-FR-1dec21-MRIF.pdf?1638559704

Motivations & Objectives for Learning Japanese or Korean

Despite Asia’s growing global significance, learning an Asian language is still relatively rare in Canada. That is especially true for non-heritage learners – that is, those who are not exposed to such languages through family or other heritage connections. However, according to APF Canada’s December 2021 National Opinion Poll, a majority of young adults aged 18-24 (61%) and 25-34 (54%) said they would be interested in learning an Asian language. What do we know about what stimulates this interest? What do learners say would sustain that desire to learn? Alternatively, are there certain factors that might discourage them from learning an Asian language?

Utility vs. curiosity

Many arguments about the value of learning a foreign language are premised on the assumption that learners are enticed by the possibility of a material benefit, such as future career prospects or the potential for higher pay. Given the economic growth rates in Asia over recent decades and the region’s strategic significance, it is no surprise that such arguments have been made in support of learning that region’s major languages. It has also often been assumed that despite these benefits, young people might be discouraged because of the perceived level of difficulty of these languages, especially compared with languages that are linguistically closer to French or English. For example, one widely cited source[1] estimates that it takes about 3.5 times as many instructional hours to reach proficiency in Japanese, Korean, or Chinese than it does for a similar level of proficiency in Germanic or Romance languages.

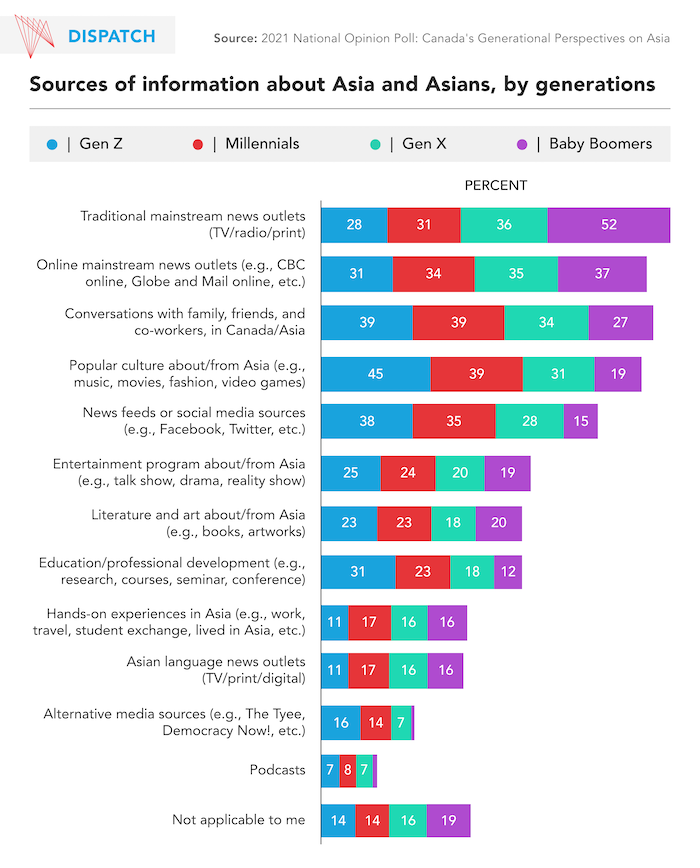

The participants in this study prompt us to reconsider both assumptions. Almost all of them described their motivations for learning Japanese or Korean as much less utilitarian in nature. For 80 per cent (20 out of 25), their interest was driven, at least initially, by a curiosity and interest in Japanese or Korean popular culture – anime, manga, and video games in the case of Japan, and K-pop (music) and K-dramas in the case of Korea. Most commented that the majority of the media they consume is Asian, not American, and that their initial desire to learn the language was so they could enjoy Japanese or Korean popular culture without having to rely on subtitles or translations.

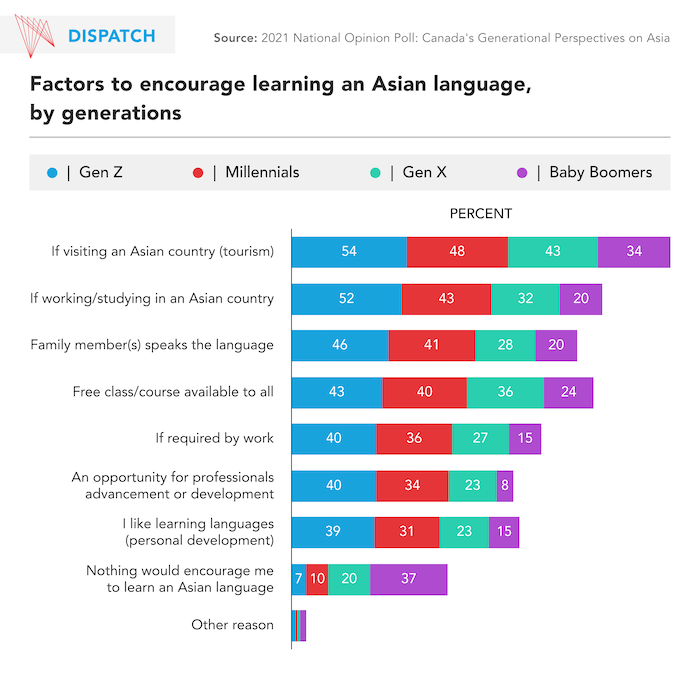

The APF Canada poll referenced above suggests that there are a range of possible motivators for young adults to learn an Asian language, including the chance to travel to or live/study in one of those countries, which ranked highest. Notably, an interest in popular culture was not included among the options in that particular question, perhaps reflecting a blind spot in our understanding of what attracts people to learning these languages.

In addition, one’s motives for learning an Asian language may not be static. As many of this study’s participants explored their interest in Japan or Korea and their respective languages, their interests expanded, and they also developed a desire to be able to communicate with people from those cultures. And several of the participants had a combination of motives, which in some cases included possible professional opportunities that were attractive because it would be a way to be engaged with the target culture or even live in that country.

Difficulty not a disincentive

While many participants acknowledged that learning Japanese or Korean can be challenging at times, the perceived level of difficulty of these languages was not mentioned as something that would have possibly dissuaded them from learning. Interestingly, however, some participants mentioned without being prompted that they did not feel that the social environment was especially supportive or encouraging. For example, several said that other people had questioned the value or utility of learning an Asian language, leaving these participants feeling that they needed to ‘justify’ why they were investing time in learning a language that is not widely spoken outside of Japan or Korea. As an illustration of this point, Samantha, an East Asian Studies major who is half American and half Iranian, recalled being asked why she was learning Japanese instead of Spanish, a prominent language in the United States, or Farsi, due to her heritage. She responded:

“The majority of what I consume is Japanese media. I want to go to Japan, and that’s my major. So obviously I learned Japanese. … I’m not going to learn Spanish on the off chance that I have to communicate with somebody who only speaks Spanish. … That’s really not as relevant to me as learning Japanese is, and learning Spanish doesn’t really have a place in the future I want. And so it’s interesting when I get those reactions, because I’m just like, ‘Okay I guess, but Japanese is relevant to me.’” - Samantha, 19

Some participants who described Japanese or Korean popular culture as the thing that sparked their interest also mentioned that there is also a downside to this association. While the appeal of Asian popular cultures is now recognized as something that has generated interest around the world in learning Japanese or Korean, several participants said there is often a stigma attached to fans of these popular cultures.

For example, Vincent and Étienne, both Japanese learners who grew up in Québec, said that when they were in secondary school, liking anime was considered ‘weird’ or childish, which they say has often led to anime fans hiding their interest. Alice, who is a fan of K-pop, said that those who liked this genre of music were not well perceived by others. Christelle, also a fan of K-pop and K-dramas, observed that there tends to be more interest in these forms of pop culture from girls and women, which may lead some to see learning Korean as a feminized hobby.

Contributing to this stigma is the emergence of terms such as “weeaboo” or “koreaboo,”[2] used to describe fans who are so obsessed with Japanese and Korean pop culture, respectively, that they appropriate or fetishize aspects of these cultures while disregarding the historical and social contexts from which these cultural products originated.

In summary, then, the role of Japanese and Korean popular cultures seems to cut both ways: it can provide an initial spark of curiosity and admiration, but also leave some learners feeling stigmatized because of the associations sometimes made with Asian pop culture fandom. However, while it may be true in some cases that consumers of popular culture do not take a deep and more critical look at the country from which that pop culture emerges, that observation can be said to be true of popular culture in general. Moreover, the participants in this study were an important corrective, or at least a very notable exception, to this assumption.

A desire for deeper awareness and closer connections

Nearly all participants in this study said their desire to communicate with native speakers of Japanese or Korean had become an important objective. This is referred to as integrative motivation – when a learner has a desire to integrate themselves with the culture of their target language and to learn the language so that they can better understand and get to know people who speak that language. It implies an openness to and respect for the other cultural community, its values, identities, and ways of life. In contrast, instrumental motivation refers to learning a language for practical reasons, such as getting a promotion at work or fulfilling a university language requirement[3].

While language learners may have a combination of motives – that is, both integrative and instrumental – most of the participants in this study were motivated first and foremost by personal interest and a positive disposition toward the culture, society, and people of Japan or Korea. That initial appeal then became a kind of gateway towards deepening their interest in and familiarity with these countries. None of the participants mentioned career prospects as their primary reason for learning Japanese or Korean. With the exception of one participant conducting academic research about the Korean peninsula, none of the others had a specific project or job that required Japanese or Korean proficiency. However, some said it was their initial personal interest in Japan or Korea – their integrative motivation – that later led them to consider a potential career related to either country. This was the case for Vincent, who said that he was undergoing a career switch to fulfil his long-held ambition of moving to Japan.

« J’ai fait de la recherche ici et là sur qu’est-ce qui est en demande, qu’est-ce qui est utile. Moi personnellement j’ai toujours eu une facilité dans la traduction français-anglais. Puis je voyais de la demande constante de traducteurs pour compagnie X, une boîte médiatique ou tourisme. … Maintenant j’essaie de faire mon bac pour avoir la certification pour qu’une fois lorsque je déménage je vais avoir le papier, ce qui va être probablement très pratique à l’embauche. » - Vincent, 35

(I did some research here and there on what is in demand, what is useful. I personally always had an ease with translating French to English. And I saw a constant demand for translators in X company, media company, or tourism. … Now I am trying to do my bachelors to have a certification so that once I move, I will have the paper, which will probably be very practical for hiring.)

Jia, who is of Chinese heritage, said that she was learning Korean for the sole purpose of travelling and experiencing Korea “off the beaten path,” but did not anticipate continuing to learn the language in the longer term. However, she mentioned professional objectives related to Japan:

“For me personally, Japan carries more of a long-term appeal. Like if I had a work opportunity there, I would be more interested in pursuing it so there’ll be that extra motivation and also the necessity of being functional and integrating myself into a work environment. Whereas in Korea, I just want to go there and have fun.” - Jia, 26

What all participants had in common was a desire to communicate with people from their target country in that country’s language, and to develop a better understanding of its culture, society, and daily life. Through their interviews, participants conveyed that they hold Japanese and Korean culture in high regard. However, in contrast to the stereotype of Asian pop culture fans as having only a superficial understanding or an overly idealized perception of these countries, many of this study’s participants demonstrated a critical awareness of these societies that extends beyond how they tend to be portrayed in popular culture and Western media. This understanding and appreciation may help challenge stereotypes about Asians and Asian-Canadians. The following section looks at this connection between language learning and cultural awareness.

[1] For quick reference, see “Foreign language training,” U.S. Department of State Foreign Service Institute, https://www.state.gov/foreign-language-training/.

[2] Koo, Se-Woong. “Who Are Koreaboos?” Korea Expose. February 8, 2022. https://koreaexpose.com/koreaboo-love-korean-culture-and-want-to-be-korean/

[3] Gardner, Robert C. “Integrative Motivation and Second Language Acquisition,” in Motivation and Second Language Acquisition, eds. Zoltan Dörnyei and Richard Schmidt. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’I, 2001).

Language Learning, Connecting with Communities, & Deepening Knowledge

Learning ‘from a distance’

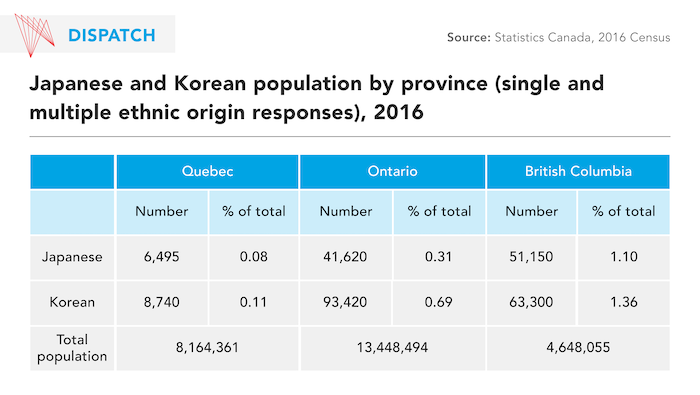

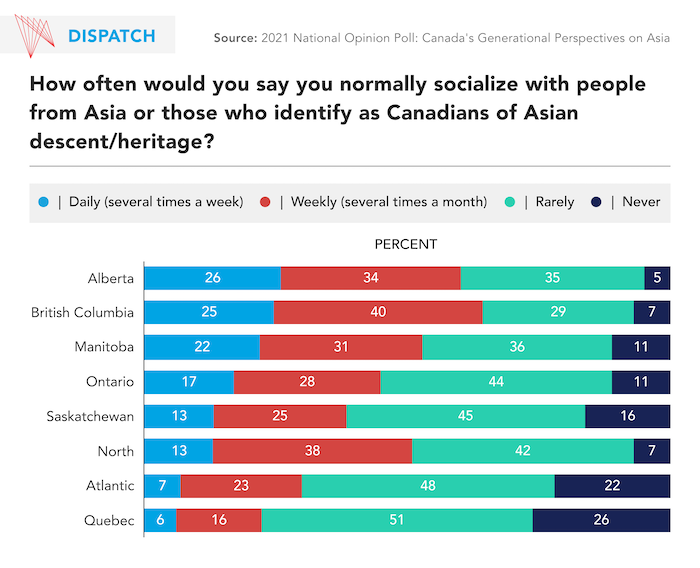

Most of the participants in this study had not visited their target country. This could be because many of them began learning the language shortly before or during the pandemic, which made travel to these countries nearly impossible. In addition, few had frequent interactions with Japanese or Korean people aside from their teachers and language exchange partners. Census and polling data sheds light on why it may be more difficult to encounter native speakers in everyday life. Compared to other provinces, Québec has fewer people of Japanese or Korean descent. Moreover, in APF Canada’s 2021 National Opinion Poll, only 22 per cent of survey respondents from Québec had daily or weekly interactions with people from Asia or Canadians of Asian descent/heritage, compared to 65 per cent in British Columbia and 45 per cent in Ontario.

Nevertheless, participants generally found other opportunities to interact with Japanese or Korean culture, especially through films, music, and online communities, as well as through hobbies such as dancing, martial arts, or cooking classes. They also said Montréal has several Japanese and Korean restaurants, grocery stores, and cultural and arts festivals. Nevertheless, while they likely had more contact with native Japanese or Korean speakers than the average Quebecer, they would like to see more of these opportunities, not just to practice their language skills but also to learn more about the target country. (A few participants noted, moreover, that such opportunities are not as available in other parts of Québec beyond Montréal.)

Some interviewees described examples of where they would welcome opportunities to learn about Japan or Korea in greater depth. Sacha, a 38-year-old who was learning Korean, said he would like to attend seminars or join informal discussion groups led by native Korean speakers who could share their stories and talk about daily life in Korea. He added that language courses tend to be too academic, focusing mostly on the acquisition of the language itself, which makes it difficult to learn about what is happening in Korea.

Vincent, a Japanese learner, said that although he enjoyed attending Japanese festivals in Montréal, he found that these events presented the culture without offering enough information.

« Il y a plusieurs événements qui approchent la culture japonaise qui sont la plupart du temps à un degré d’introduction. Quand il y avait le hanami ... il n’y a personne qui va te détailler sur le sujet. Je comprends pourquoi, parce que c’est fait pour être un peu plus un point d’approche pour le public général. » - Vincent, 35

(There are many events that approach Japanese culture that are mostly at an introductory level. When there was the hanami … there was no one who would offer you details about the topic. I understand why, because it’s meant to be more of a starting point for the general public.)

(Note: Hanami is the Japanese custom of appreciating the beauty of flowers, such as in the spring. A hanami flower festival was held in April 2021 in Montréal showcasing different aspects of Japanese culture such as gastronomy, music, manga, and fashion.)

According to Philippe, who was conducting academic research on Korea, learning languages and culture happens through immersion and real-life interactions.

« Les cours, ce n’est pas la meilleure façon d’apprendre le coréen. Apprendre une langue, il faut que tu sois immergé là-dedans, tu ne peux pas l’apprendre par coeur … La vraie culture coréenne pour moi c’est les marchés, les madames, aller négocier les prix » - Philippe, 25

(Classes are not the best way to learn Korean. Learning a language, you have to be immersed in it, you cannot learn it by heart … The real Korean culture to me is the markets, the ladies negotiating prices.)

Some participants said they had built local communities based on a shared interest in Japan or Korea and in language-learning. Daniela said she often met up with her friends to listen to K-pop and talk about their favourite Korean dramas. Roxanne and Noémie found it motivating to be learning a language with friends who were also interested in Korean and Japanese popular culture, respectively.

Trying to fill the gaps

As many of the young adults interviewed for this study indicated, their interest in learning Japanese or Korean was related to their interest in Japanese or Korean culture, and they viewed making connections with others who are knowledgeable about one of these places as an important complement to this pursuit. These self-motivated activities did not necessarily translate into taking a greater interest in following current events in those two countries. In fact, very few participants said that they regularly did so, usually due to a lack of time or interest. Some said they were aware of some current events in these countries through social media and that they watched YouTube videos or followed Twitter that discussed daily life, culture, and news about one of these two countries. Others said they sometimes received information about current events from their Japanese or Korean friends.

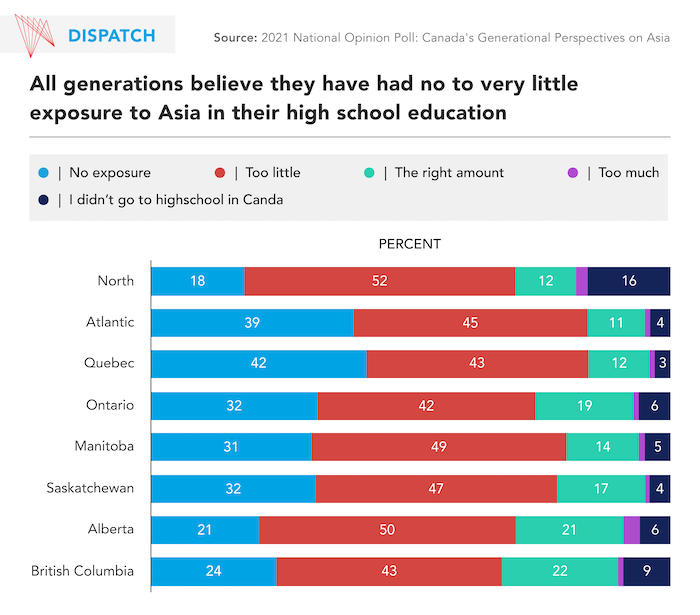

Some participants did note that they felt there had been some gaps in their earlier, formal education about Asia. A majority, including those who grew up in Québec, did not have a base of formal education about Asia in their primary or secondary schooling. In this regard, Québec is not an outlier – according to APF Canada polling, a majority of Canadians said they had little to no formal education about Asia in high school, although this figure was highest in Québec (85%).

Given this lack of exposure to Asia earlier in their lives, some participants purposely chose research topics in their post-secondary studies related to Japan or Korea so they could learn more about these countries. In fact, participants like Lily, a Korean learner from New Brunswick majoring in East Asian Studies, said that it was only in university that she started learning about Asia through her coursework.

“When I got to McGill, I was learning all of these things that I felt like I should have already known. Not necessarily just about Korea but other countries as well ... I remember one thing that was a big shock to me in one of my first-year courses is that the Korean War isn’t technically over. I was blown away by that. We never learned about that in school, we never even talked about the Korean War.” - Lily, 22

Reflecting on her own relative lack of formal education about Asia, Daniela, a Korean learner, said:

“To me, Europe and America they are connected. The other part that has always been a mystery to many of us is the Asian part of the world. The fact that I had to discover [it] through manga is really interesting. But I feel like you can discover a lot more, more than just through a show which we know is fictional.” - Daniela, 19

At the same time, for participants like Léa, the lack of exposure to Asia and Asian cultures added to their curiosity and desire to learn more.

« Quand je m’intéresse à la culture japonaise, à la culture coréenne ou à la culture asiatique de l’Est, c’est un choix ‘autre’. C’est un univers qui s’ouvre devant nous qu’on ne connaissait pas … Les gens sont intéressés, les gens ont envie de les connaître. On a moins été exposés donc on a envie de découvrir. » - Léa, 26

(When I am interested in Japanese culture, Korean culture, or East Asian culture, it’s an ‘other’ choice. It’s a universe that opens up to us that we did not know … People are interested, people want to understand. We have been less exposed, so we want to discover.)

In pointing to another gap in their education about Asia, many acknowledged that they knew relatively little about other parts of that region and believed that more should be done to develop greater awareness about the region as a whole – an acknowledgement relevant to the survey result mentioned in the introduction to this report that roughly half of Québec‘s population is either very or somewhat interested in learning more about Asia.

Returning to the issue of popular culture, some participants, while noting that it can be a driver of interest in language-learning, also cautioned that we should be aware of its possible limitations in fostering deeper awareness and connections. For example, Mathilde, whose spouse is Korean, found that in her experience, some Korean people hesitate to open up because of a perception that others were only interested in them because of popular culture.

« Les gens ne veulent pas parler de leurs origines de peur d’être juste associés à ça, du pays où ils ont grandi … [Leur perception] c’est plutôt : tu ne vas pas pouvoir me comprendre, alors pourquoi tu essaies de me comprendre ?

Quand on apprend la langue … c’est difficile parce qu’on essaie d’en apprendre un peu plus sur la culture, mais on ne veut pas s’immiscer … ne pas être respectueux envers la culture non plus. Comment je peux te faire savoir que je m’intéresse vraiment à toi et pas juste à des dramas et de la K-pop ? » - Mathilde, 30

(People don’t want to talk about their origins for fear of being associated with just that, with the country where they grew up … [Their perception] is more like: ‘you wouldn’t be able to understand me, so why are you trying to?’

When you learn the language … it’s hard because you try to learn a bit more about the culture, but you don’t want to interfere … be disrespectful towards the culture either. How can I make you aware that I am really interested in you and not just in dramas and K-pop?)

Mathilde suggested that to bridge this gap, people should develop an understanding of Korea’s past and its current position in the world and have patience when meeting Korean people. In her experience, while popular culture may provide a starting point for greater interest for Japan or Korea among youth, this should be complemented with opportunities to learn about these countries’ societies, histories, and cultures, especially directly from Japanese and Korean people.

Keeping an open mind

While this study’s participants were enticed to learn the Japanese or Korean language because of positive feelings about their popular cultures, overall, they were still able to develop a nuanced and critical awareness of these countries. This finding held for both those who had and had not visited Japan or Korea. Some conceded that, at first, they held a very idealized image of these countries, but noted that these perceptions changed over time as they learned more.

One example that came up in several interviews was the idea of a paradox, or contrast, in both Japanese and Korean societies. Many participants perceived these places as rich in tradition, but also highly modern. Some participants thought of natural landscapes alongside bustling cities and skyscrapers. This idea of contrast extended to personal interactions with people, as observed by Cédric and Léa, two Francophones learning Korean, who both remarked that although Koreans appear to be cold on the outside, they can also be very warm-hearted and welcoming once they get to know you.

Indeed, many participants had a mix of both positive and negative perceptions about these countries. Many appreciated values such as respect for elders and an ethic of hard work but were also critical of the strict social hierarchies and discrimination against women and members of the LGBTQ community. These participants said that they were aware that Japan and Korea are not perfect, and some mentioned what they recognized as a gap between reality and what popular culture and media tend to portray.

In addition, a few participants specifically critiqued Japanese and Korean soft power and nation-branding.

« Ça ne me tente pas de te répondre avec de la propagande sud-coréenne. Je pense que la Corée du Sud est un pays qui a tellement un marketing de son identité incroyable qui fonctionne tellement bien … J’adore tellement la Corée mais en même temps il y a un côté fake que j’haïs. » - Philippe, 25

(I don’t want to answer with South Korean propaganda. I think South Korea is a country that has an incredible identity marketing that works so well … I really love Korea but at the same time there is a fake side that I hate.)

“Last semester I took a class on 20th century Chinese history. We talked about China and Japan and that was interesting. In my Korean literature class, we talked about literature from the colonial period … The kind of soft power approach is ‘manga, anime, Japan is so nice!’ But look at what happened. There’s history and there’s soft power – that’s a more complex representation of Japan.” - Hannah, 20

David, an Anglophone Japanese-learner, said that how Japan is portrayed in the West tends to be stereotypical and sometimes inaccurate, especially when it comes to samurai or ninja characters in Hollywood films. Étienne, who is Francophone and learning Japanese, said that Western media sometimes exaggerates certain facts about Japan, such as trains being overcrowded and restaurants refusing to serve foreigners. While he acknowledged that there was some truth to these stories, he said that he rarely encountered these situations when he visited Japan.

However, participants were not necessarily dismissive of all negative portrayals, and several who have not been to Japan or Korea expressed concerns about how they might be treated or perceived as foreigners when they go:

« … si je finis enfin par aller au Japon pour au moins un an, je n’ai pas le goût d’être mise à un pied plus bas que les hommes. Mais ça va quand même être le cas peu importe ce que je fais. Aussi le fait que je ne suis pas Japonaise, j’ai des traits d’une femme blanche. Je ne sais pas si les gens là-bas vont me regarder bizarrement. Je ne penserais pas, surtout dans les grosses villes. Mais c’est quand même quelque chose que je me demande. » - Noémie, 21

(… if I end up going to Japan for at least a year, I don’t want to be put lower than men. But that will be the case no matter what I do. Also, the fact that I am not Japanese, that I have features of a White woman. I don’t know if people there will look at me weirdly. I wouldn’t think so, especially not in big cities. But it’s still something that I wonder.)

Christelle, a Korean-learner of Haitian origin, shared similar concerns regarding the perception of foreigners in Korea:

« J’aimerais visiter [la Corée] … mais ça reste quand même uniforme comme culture. Il y a beaucoup de monde qui ne sont pas habitués de voir des personnes étrangères ou noires. Quand j’y pense, ça peut être stressant.» - Christelle, 24

(I’d like to visit [Korea] … but it’s still a culture that is quite uniform. There are a lot of people who are not used to seeing foreigners or Black people. When I think about it, it can be stressful.)

Most participants said that, over time, they were able to develop a better, more nuanced understanding of Japan or Korea, both positive and negative aspects. However, their apprehensions did not discourage them from continuing to learn Japanese or Korean or making plans to visit and experience Japan or Korea in the future.

An interesting example of how language can be a bridge to greater familiarity with the target country and culture is something several participants mentioned – namely, that learning Japanese or Korean helped them better understand cultural aspects such as social hierarchy, especially given the use of honorifics and formality levels in both languages. Sociolinguists refer to ‘intercultural communicative competence’ to emphasize the ability to not only speak a language correctly, but also in a socially appropriate way – in other words, with intercultural competence[1]. While language is not the sole component of intercultural communication and awareness, it can be an important factor.

Samantha, for example, discussed the differences between addressing a teacher in Japan and a teacher in North America, and reflected on how she would adapt her speech style in Japan:

“… If I go to live in Japan – because I think I’m a pretty outspoken person – it would be interesting to see how that part of my personality blends with a language that is very restricting … It’s really important to respect the culture and speak formally to people when you have to. But at the same time, I feel like my Western way of speaking can’t really entirely coexist with that structure.” - Samantha, 19

Many participants said that it would be impossible to truly understand a country and its culture, society, and history without knowing the language, as there is a limit to what one can learn through speaking only French or English. At the same time, they believed that learning a language without being interested in its culture would be challenging, especially because it would be hard to sustain motivation when learning relatively difficult languages such as Japanese or Korean.

Others said that learning their target language made them adopt a different mindset and attitude. When asked why language-learning should be encouraged, most participants said that it can make you more open-minded and tolerant towards different cultures, although this will be stronger for some learners than for others.

But in the context of Québec, where French is the only official language, did any of these interviewees feel that encouraging the learning of Asian languages as part of the province’s foreign policy pivot toward Asia would conflict with the commitment to sustaining that language?

[1] Byram, Michael and Irina Golubeva, “Conceptualising intercultural (communicative) competence and intercultural citizenship,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication, ed. Jane Jackson. (London: Routledge, 2020)

Asian language learning in Canada & Québec

To contextualize participants’ views on promoting Asian-language learning in Québec, it is helpful to reflect first on the approaches of Canada and Québec to diversity and official language(s). This helps us understand why, despite seeing clear personal or societal benefits to learning an Asian (or any other third) language, several participants did not necessarily feel that it should be prioritized or formally encouraged by the government.

The idea of Canada as a multicultural society recognizes that Canadians come from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds. The 1988 Multiculturalism Act seeks to preserve, enhance, and incorporate cultural differences into Canadian society and ensure equal access and full participation for all Canadians in different spheres of Canadian life. Canadian multiculturalism is also underpinned by institutional bilingualism, the capacity of federal institutions to operate in both French and English.

Canadian multiculturalism has been rejected in Québec, as many have argued that it undermines Québec‘s unique status by putting Francophones on the same footing as all other cultural groups in Canada. As a result, Québec has adopted an intercultural model[1], which is based on the idea of the integration of various minority communities into the majority culture via francization and secularization of the public domain. Two important considerations underlie this approach:

- There is a majority culture within the nation of Québec, which results in a specific vision of nationhood, identity, and national belonging. In contrast, there is no majority culture in Canada, as diversity defines national identity.

- Francophone Quebecers constitute a minority in English-speaking North America, which is why an emphasis is placed on language protection as necessary for integration and collective cohesion. Canadian multiculturalism does not reflect similar concerns over language protection, as English is not under threat.

According to la Charte de la langue française (Charter of the French language, commonly known as Bill 101), all children in Québec must be educated in French until the end of secondary school. Although the government continues to promote and protect the French language and Québec culture, francophone Québec’s fragility is accentuated by globalization, the growing presence of immigrants and the uncertainty about their francization, and the unresolved question regarding Québec sovereignty. Bill 21 on the laïcité of the state and the recently adopted Bill 96 on the official and common language of Québec are two recent examples of the ongoing debate regarding Quebec’s integration model. In this context, a push for learning Asian languages could be seen as competing with efforts to protect and promote French.

Although participants were not asked about their views of multiculturalism or interculturalism, their opinions regarding Asian language learning in Québec largely reflected issues of identity, integration, and diversity in the province.

Articulating the benefits of learning an Asian language

Participants were asked whether they would encourage others, such as friends or family, to learn an Asian language. The majority of participants said that they would, and highlighted reasons similar to their own motivations for learning Japanese or Korean. These included understanding a target country and its culture, or communicating with native speakers of these languages, especially if the prospective learner already had a strong interest in Japanese or Korean culture. Although not often included in their primary motivations for learning Japanese and Korean, participants also said that language-learning in general has cognitive benefits and can help one develop an appreciation for their own culture.

However, participants also articulated the benefits of language-learning for society as a whole, such as:

- Increasing open-mindedness and tolerance towards others

- Making our society more welcoming to new immigrants and promoting diversity

- Improving Canada-Asia and/or Québec-Asia ties

Negative perceptions can lead to a lack of interest

As a significant number of people, especially youth, are interested in learning Japanese or Korean due to the appeal of those countries’ popular cultures, some participants argued that offering language courses would cater to an existing and growing demand. However, a few others said that even if the government officially encouraged learning Asian languages, they did not think that many people would be interested. According to them, few people in Québec want to learn an Asian language or any third language. While Montréal is one of the most multicultural and multilingual cities in Canada, those who live in less diverse regions may hold prejudiced or misinformed views about people of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Noémie, who has family and friends outside of Montréal, thought that some of her acquaintances had « une pensée très arriérée » (a very backward thinking) and recalled their reaction to her learning Japanese:

« Quand je dis que j’apprends le japonais au gens, ils rient de moi. C’est pas drôle ! Il y a beaucoup de préjugés à propos de ça, je dirais. Dès que je dis que j’apprends le japonais ils vont faire l’accent raciste chinois alors que ça n’a rien à voir [avec ça]. Quand je parle des fun facts de la langue japonaise à mes amis … ils ne sont pas très ouverts. Mais ils n’apprennent pas de langues non plus. Ils parlent mal anglais, ils ne parlent pas espagnol. » - Noémie, 21

(When I tell people that I learn Japanese, they laugh at me. It’s not funny! There is a lot of prejudice against that, I’d say. Once I tell them that I learn Japanese, they would do the racist Chinese accent while it has nothing to do [with that]. When I talk about fun facts of Japanese language with my friends … they’re not really open. But they don’t learn languages either. They don’t speak English well, they don’t speak Spanish.)

Léa, who is from France, attributed a lack of interest in Asian languages to a fear of China and overall anti-Asian sentiment in the West.

« Les gens ont peur de l’Asie. On a tellement matrixé les gens avec la Chine et la Chine c’est mauvais. C’est un discours populaire… Malheureusement c’est un refrain des sociétés occidentales qui ont peur ... C’est trop peu d’exposition et un discours du gouvernement qui n’encourage pas l’ouverture d’esprit. » - Léa, 26

(People are scared of Asia. We negatively influenced people’s perception of China, and China is bad. It’s a popular discourse … Unfortunately, it’s a line from Western societies that are scared … It’s too little exposure and a discourse from the government that does not encourage open-mindedness)

Philippe, who is Québécois, echoed similar sentiments, adding that older generations – including those in charge of policymaking today – grew up during a time when Asia was very different.

« Nos parents quand qu’ils étaient jeunes … l’Asie c’était des personnes pauvres. Maintenant c’est Kim Jong-un et puis la Chine c’est des méchants. Donc eux autres, nos parents et les personnes qui voudraient promouvoir [l’apprentissage des langues], ils n’ont pas connu le Japon anime qui a séduit tous les jeunes de ma génération, puis ils n’ont pas connu les K-dramas » - Philippe, 25

(Our parents when they were young … Asia was poor people. Now it’s Kim Jong-un and China is mean. So for them, our parents and people who would like to promote [language-learning], they did not know the anime Japan that seduced all the youth of my generation, and they did not know K-dramas.)

For Canada and Québec to position themselves as global economic players, especially in the Indo-Pacific, investment in language education can help signal their commitment to long-term engagement with the region and can help shift general attitudes on language-learning and reduce the stigma against Asia and Asian people.

Asian language-learning vis-à-vis other linguistic priorities

When asked whether promoting Asian language-learning would conflict with linguistic priorities such as bilingualism in Canada and the protection of French in Québec, many participants (21 participants, of whom eight are Francophone) said that they did not see protecting French and learning an Asian language or any other third language as mutually exclusive goals. According to them, knowing another language is simply an additional asset.

For several participants, it is English – not Asian languages – that is more threatening to the position of French in Québec. David, whose native language is English but is fluent in French and several other languages, said he believes the more different the language (from French), the less of a threat it is to French.

Étienne, who is learning Japanese, said that although there should be more opportunities to learn Asian languages, he believed that children should only start learning a non-heritage third language in secondary school, after they have mastered both French and English.

Gabriel, a Francophone with Italian and Brazilian roots, agreed that while the priority in Québec is to first master French and then learn English, he would have appreciated being able to start learning Japanese earlier. He recalled that when he was 14, he could not register for classes at the Japanese community centre despite his strong interest because of an age restriction.

« L'opportunité d’appendre des langues plus jeune ça serait super. Je pense que sauf si le jeune un de ses parents est d’ethnicité japonaise ou coréenne, c’est vraiment difficile pour lui d’apprendre s’il est intéressé envers la culture. Même si le parent était intéressé, ou qu’il voit que le jeune est intéressé et il veut l’inscrire, la seule opportunité qui est sûre c’est à l’université. Mais le monde devra attendre longtemps avant d’y arriver ou il ne va juste pas y arriver du tout. » - Gabriel, 18

(The opportunity to learn languages younger would be great. I think unless the kid one of his parents is of Japanese or Korean ethnicity, it’s really difficult for him to learn if he is interested in the culture. Even if the parent was interested, or that they see that the kid is interested and wants to sign him up, the only opportunity that is certain is at university. But people will have to wait for a long time before getting there, or they might not get there at all.)

Issues of access to learning materials and the dominance of English

While all participants said they faced different challenges with learning Japanese or Korean, several Francophone learners mentioned that they often had to juggle French, English, and their target language. According to them, there are fewer resources such as textbooks, videos, or apps designed for language learners who are not native English speakers. This is especially the case for Korean, which has become popular relatively recently. Furthermore, many non-credit language courses are taught in English, as language teachers are often new immigrants to Québec for whom French is their third or fourth language.

Nevertheless, Francophone participants said that they were able to overcome such challenges by looking up definitions or explanations by themselves. Some said that because they are bilingual or proficient enough in English, using Japanese and Korean language-learning resources and materials designed for native English speakers was not a significant challenge.

Several participants even said that they believed learning Japanese or Korean through English was easier, in part due to the abundance of learning materials for English speakers, but also because they are so used to using social media, doing research, or consuming American pop culture in English that learning an Asian language through English was not unusual to them.

Conclusion

The participants in this study were mainly bilingual or multicultural and lived or attended school in Montréal, a diverse and cosmopolitan city. While they do not represent all youth in Québec, we can derive several important takeaways from their opinions and experiences.

- It important to underscore, again, that most participants saw learning an Asian language as a personal decision, even though they themselves see many upsides to it.

- Although participants responded to the question regarding potential conflict with language policies in a number of different ways, these views are not entirely mutually exclusive. Rather, they illustrate the complexity of issues regarding diversity and language protection in Québec.

Given the need for Canada and Québec to respond to a world that is defined by Asia’s growing prominence by encouraging the development of ‘Asia competence’ in younger generations, these language learners’ perspectives raise important questions for policymakers, educators, and society at large: What are the most effective ways for policymakers, educators, and society at large to support and encourage learning about Asia, especially Asian languages?

[1] Bouchard, Gérard. “What is Interculturalism?” McGill Law Journal, 56:2 (2011). https://lawjournal.mcgill.ca/wp-content/uploads/pdf/2710852-Bouchard_e.pdf

Summary Findings & Recommendations

We know that pop culture from Japan and Korea is driving the increase in demand for learning Japanese and/or Korean among youth around the world, and Montréal is no exception. While consumption of Japanese and Korean pop culture varied among this study’s participants, the majority said that anime and manga, or K-pop and K-dramas, sparked their curiosity in Japan or Korea.

These language learners were driven by personal interest and integrative motivation – the desire to communicate with native speakers and to integrate with the culture of their target language. Generally, these Japanese and Korean language-learners were motivated by things other than instrumental reasons, which are usually tied to professional or academic goals such as getting a promotion or fulfilling course requirements. They are also open-minded and respectful of Japanese and Korean culture and people, as evidenced by their efforts to gain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of their target country.

Popular culture can provide the initial ‘pull’ or introduction to Japan and Korea, motivating several young people to begin studying Japanese or Korean language, but it is important that learners are provided with resources and opportunities to deepen their cultural awareness of Japan and Korea both inside and outside of language classrooms.

Recommendation 1: Build and sustain youth’s language-learning trajectory

While popular culture can spark initial interest in Japan and Korea among youth, sustaining long-term interest requires policymakers and educators to be attentive to the diverse cultural, linguistic, and academic backgrounds and motivations of young language-learners.

Improve access for Francophone language-learners

Several Francophone language-learners interviewed in this study experienced some difficulty learning Japanese and Korean through English, their second language, and most participants agreed that there were few language-learning materials for Francophone and non-native English speakers. The majority did not find these to be significant challenges to learning Japanese or Korean. However, we recognize that our study focused on youth in Montréal – which may have contributed to a greater-than-average number of bilingual or multilingual participants in our sample. Investing in translation and development of resources and materials for Francophone and non-native English-speaking learners would create better, more equitable access to Japanese and Korean language-learning opportunities.

Ensure continuity in language-learning

Japanese- and Korean-language courses in Montréal are only offered in tertiary education (mainly in universities, and in some CEGEPs in the case of Japanese), non-credit courses in community centres and language schools, or in private tutoring. Youth who have an early interest in Japanese or Korean usually do not begin learning the language until they are in their late teens by enrolling in non-credit courses (usually age-restricted), or by taking Japanese and Korean language only when they attend university. A late start to language-learning gives youth less time to reach proficiency, which especially affects those who hope to use their language skills in the future in a professional setting. Furthermore, the lack or absence of courses could be discouraging for language learners, making them more likely to abandon their efforts.

Introducing Asian languages as early as possible, especially in formal education, can help build a pathway for youth to pursue language-learning in university and beyond.

Support professional and personal language-learning journeys

As our study shows, not every young Japanese- or Korean-language learner hopes to move to their target country or to pursue a career in which their target language is essential. Some study languages as a hobby, just like one would take up piano or yoga. However, it is important to recognize language-learning is an enriching experience no matter what a learner’s ultimate goal or use of the language may be. Language courses and programs should include resources and guidance adapted to different learners’ abilities, needs, and motivations – which can and often change over the course of their language-learning journeys.

Recommendation 2: Create opportunities for young adult connections through existing points of contact

The majority of young Japanese and Korean language learners interviewed in this study enjoyed attending local festivals where they could try new foods, learn about traditions in their target country, and meet native speakers and other youth interested in Asia. However, several participants mentioned that these events tend to be too small or too crowded, and they offered only a glimpse of Japanese or Korean culture without going into much depth.

More funding for festival and community organizers could help increase capacity and further diversify programming at public events. For young language learners interested in deepening their knowledge of Japan, Korea, and Asia more broadly, a budget earmarked for smaller and more intimate gatherings would help create greater opportunities to interact with and learn directly from native speakers.

Such gatherings could be organized on the side of major festivals and events. Sacha suggested holding seminars or informal discussion groups with Koreans in Montréal where attendees can learn about contemporary issues in Korea. Such opportunities would be especially relevant for those who have limited opportunities to take Asia-related coursework that tends to only be available at universities.

Mathilde said language exchange groups are a good way to connect with members of the Korean community in Montréal but encouraged participants to do other non-language related activities afterward to socialize and get to know each other on a more personal basis.

Gabriel suggested creating a centralized hub that brings together different Japan-related organizations in Montréal, such as the Japanese community centre, campus-based clubs, sports associations, and language schools. This one-stop-shop would make resources and opportunities related to Japan more easily accessible to the public and help build connections between different communities.

Recommendation 3: Connect youth to an ecosystem for building ‘Asia competence’

Proficiency in a language is an important tool in developing cultural awareness. However, exposure to Asia often comes late in students’ formal educational experiences. Nearly all participants in our study said they had little to no exposure to Asian history or culture in primary and secondary education. Instead, their interest in Japanese and Korean culture prompted them to independently seek opportunities to learn more about these cultures outside the classroom.

With the Indo-Pacific now at the forefront of many nations’ foreign policies, including Québec's, building and sustaining relationships with counterparts in Asia requires a population that is engaged and informed about the region. Furthermore, the alarming rise of anti-Asian violence in Canada has led to calls from Asian communities for the inclusion of lessons about the history of Asians in North America in public schools to combat racism. Young language-learners interviewed for this study and Canadians across the country polled by APF Canada agree that more emphasis should be placed on teaching about Asia.

One of the most critical issues we face in preparing young generations to more effectively engage with the Indo-Pacific is how to build a student pipeline into Asia-related professions. The growing popularity of Asian popular culture sparked a strong interest in Asia among youth, which has drawn many students toward Asian studies. However, many East Asian Studies majors interviewed for this study said that while they hoped to leverage their knowledge and language proficiency for their careers, few had a clear idea of the kind of job opportunities that exist in this field.

To build a pipeline for Asia-related careers, we need to connect learning opportunities and create educational models that start long before students enter university and continue beyond graduation.

Becoming a translator may be an obvious path for many passionate language-learners, but for most people, language skills need to be combined with something else, such as hard skills or industry-specific knowledge and experience.

Being fluent in a language does not guarantee a job, but language skills and international experience can give applicants an edge. Students, educators, and employers need to understand and articulate the value of knowing a different language, while working together to address the skills gap.

Methodology

Semi-structured individual interviews were considered the most appropriate research approach given the nature of this study, which requires 1) an in-depth approach to understanding personal motivations behind learning Asian languages in an environment that stress the importance of French; and 2) an exploration of perspectives and opinions on Asia, and Quebec and Canada engagement with Asia, through language learning and intercultural exchange.

Efforts were made to seek out participants of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds who are studying Japanese and/or Korean. A convenience sample of language learners was obtained through advertisements shared in online language-learning groups and through institutional mailing lists of universities and language schools.

Respondents were asked to fill out a recruitment survey that provided the researcher with basic information regarding their background and experience with Japan and Korea. The interviews were held virtually through Zoom and conducted in either French or English depending on the participants’ preference. Each interview lasted from 30 to 60 minutes. There was no compensation associated with participation in the study. The interviews were recorded with prior consent and were independently transcribed and analyzed by the lead researcher.

Number of interviews: 43 people responded to a recruitment survey; 25 people were interviewed.

Language learning:

Japanese = 10

Korean = 15

Participant age-range: 18-38

Gender identity:

Female = 15

Male = 9

Other = 1

Ethnic and cultural identity:

White/Caucasian = 16

Non-White/Non-Caucasian = 9

Mother tongue:

French = 14

English = 4

Allophone (not French, English, or an Indigenous language) = 7

Positionality: This report is the work of a researcher who is of Vietnamese heritage, was born and raised in Montréal, and has personal experience learning both Japanese and Korean. This researcher also has experience in leading youth- and education-related programming to build Asia competency among young Canadians. While all efforts have been made to maintain objectivity, the researchers’ experience, knowledge, and biases may affect the way the data is interpreted.

Notes:

- Although we refer to participants of this study as young adults in Montréal, we note that not all participants were physically located in Montréal at the time of the interview or through the course of this research. Furthermore, we did not restrict participation to solely Canadian citizens or permanent residents. However, all participants regardless of their ethnic, cultural, or national origins have lived in Montréal and/or studied Japanese or Korean at a Montréal-based institution.

- During the interviews, the term ‘Korea’ was used to include the culture and history of the entire peninsula. However, with the exception of one participant, Korean learners in this study did not make any mention of North Korea. Unless otherwise specified, the terms ‘Korea’ and ‘Korean’ used in this report refer to South Korea.

Endnotes

Ministère des Relations Internationales et de la Francophonie. Stratégie territoriale pour l’Indo-Pacifique. Québec : Gouvernement du Québec. 2021. https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/relations-internationales/publications-adm/politiques/STR-Strategie-IndoPacifique-Long-FR-1dec21-MRIF.pdf?1638559704

Koo, Se-Woong. “Who Are Koreaboos?” Korea Exposé. February 8, 2022. https://koreaexpose.com/koreaboo-love-korean-culture-and-want-to-be-korean/

Gardner, Robert C. “Integrative Motivation and Second Language Acquisition,” in Motivation and Second Language Acquisition, edited by Zoltan Dörnyei and Richard Schmidt. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, 2001.

Byram, Michael and Irina Golubeva. “Conceptualising intercultural (communicative) competence and intercultural citizenship,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication, edited by Jane Jackson. London: Routledge, 2020.

Bouchard, Gérard. “What is Interculturalism?” McGill Law Journal, 56:2 (2011). https://lawjournal.mcgill.ca/wp-content/uploads/pdf/2710852-Bouchard_e.pdf

Appendix: Interview Questions

Motivations and objectives for language learning

- Why did you decide/What motivated you to study Japanese/Korean language? (reasons/motivations)

- Do you have any specific goals in mind that you want to accomplish through learning this language? (goals/reasons/expectations)

- [For students who have been learning for several years] Why have you continued learning Japanese/Korean language for _____ years? What is/are the reasons for continuing with your study? (long-term motivations/reasons)

- Have you faced any challenges regarding the quality or availability of learning materials? (barriers to language learning)

- Are materials available in your first language? (particularly for Francophone)

Perceptions of Japan/Korea

- Do you have any contact with Japanese/Korean culture, society, history and people beyond your language learning network? If yes, can you elaborate a bit more on that point. (network and awareness)

- When thinking about Japan/Korea, what are the first things that come to your mind? (first impressions)

- What aspects of Japanese/Korean culture, society, and history are you most interested in? (awareness and interest)

- How do you build your knowledge/awareness of Japan/Korea? Do you use sources, some more than others? (source of information/awareness)

- Do you follow current events or news about or from Japan/Korea? If yes, why? What is the latest news you can remember?

- Have your perceptions of Japanese/Korean culture changed after you began taking language lessons? If yes, how? (change in perceptions due to language learning)

Ideas on expanding Montréal’s/Quebec’s/Canada’s knowledge of and connections to Asia

- Have you faced any challenges when seeking to learn more about and/or engage with Japan/Korea? Can you elaborate a bit more on that point? (barriers to building awareness)

- What more can/should the federal or provincial government do in this regard? (government role)

- In your opinion, would the promotion of Asian language-learning compete with existing language policies regarding Canadian bilingualism or the protection of French in Quebec? (government role/bilingualism)

- Will you recommend learning an Asian language to other Quebecers or Canadians? If yes, why? (personal role)

- In your opinion, what are some effective ways to motivate other Quebecers and Canadians to learn about Japan/Korea (or other Asian countries/cultures)? (awareness methods)

Appendix: Participants’ Cultural, Ethnic, & Linguistic Backgrounds

Of the 25 individuals interviewed, 16 were Caucasian (White) and nine were non-White (non-Caucasian). The majority of participants (14 of 25) identified French as their mother tongue. However, four of them were French nationals living in Quebec while the rest were Quebecois. With the exception of two participants who were American, all others could speak French and English and several of them can also speak other languages as well such as Spanish (learned at school) or their heritage language. (See Appendix for full demographic details).