Delegates at China’s annual ‘Two Sessions’ meetings in March formed laws covering everything from new GDP targets and death education in schools, to legal tools for fighting economic battles and additional days off around the Lunar New Year holidays. These changes, large and small, are part of the thousands of proposals put forward to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), China’s highest legislative body, and the National People’s Congress (NPC), the top political advisory body in China.

With past sessions seeing large policy shifts, and amid ongoing pressure from the trade war with the United States, the 2019 Two Sessions received a high degree of attention, both domestic and international. The annual meeting is nicknamed the ‘Two Sessions’ because both the NPC and the CPCC meet; while both are ostensibly policy-generating bodies, their functions have been critiqued as more ceremonial than substantive.

Policy priorities and political theatre

The Two Sessions event, which ended on March 15, is often the first time that China watchers can see legislation and policies that directly cover the world’s most populous country. With much of the policy direction of China still actually decided behind closed doors, the Two Sessions are themselves little more than political theatre. The NPC and CPPCC proposals have little impact on the county’s legislative process, which the Communist Party of China (CPC) leadership largely controls. Observers watch the Two Sessions, then, not for the content they create, but as an opportunity to take a peek under the hood of the CPC’s annual priorities.

Delegates listen to Chinese Premier Li Keqiang's speech during the opening of the 'Two Sessions' at The Great Hall of the People on March 5, 2019 in Beijing, China. | Photo: Andrea Verdelli/Getty Images

Part of the challenge facing the Two Sessions is structural: the Sessions’ content has to be wide-ranging in order to address the policy choices affecting a country of 1.4 billion people in the second largest global economy, and yet the two bodies meet for less than two weeks each year.

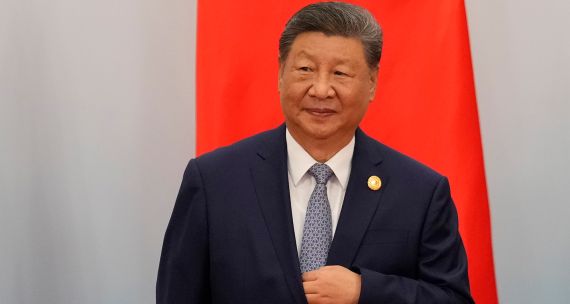

The CPC, meanwhile, has also disempowered the thousands of delegates to the NPC and CPPCC from most means of challenging the Party. Some of the most controversial proposals from delegates, including legislating rights to legal counsel during interrogations, were censored and removed from online circulation in the lead-up to the 2019 Sessions. This year’s tightened constraints on delegates may be driven by CPC concerns about political instability during a period of heightened domestic pressures, impacts of the trade war included. Noted one commentator, “Clearly [Chinese President] Xi Jinping is under pressure and precisely because he’s under pressure, feeling slightly vulnerable, not terribly but slightly vulnerable. He’s just not going to allow anybody to say anything.”

Observers frequently criticize the sessions as rubber-stamps for pre-determined diktats from the CPC. “It isn't the smartest people that rise to the top,” said one China researcher at the Australian National University, on why new policy is unlikely to arise from a forum populated by newly rich and celebrity session members. In recent years, a large share of China’s wealthiest class have become delegates – one in seven of China’s richest were delegates in 2015. In addition to the rich, there are those who are rich and famous: this year’s delegate list also included such international celebrities as Yao Ming of NBA fame and actor Jackie Chan. But these celebrity delegates are not ultimately the largest stars of the show: those roles, and the credit for pushing through approved policies, largely falls on seasoned voices that the CPC vets and supports.

Chinese delegates from Xinjiang province arrive for the closing meeting of the National People's Congress on March 15, 2019 in Beijing, China. The annual 'Two Sessions' gathering lays out the government's road map for the year ahead, including economic growth targets, diplomacy, and military spending. | Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Announcements on the sidelines of the sessions also raise criticisms. This year, they included vows to continue mass detentions in Xinjiang and communiques that Tibet is restricted to rights groups and overseas activists.

Global pushback and domestic scrutiny

Internationally, China is facing pushback for its controversial Belt and Road Initiative, high-tech ambitions, increasingly assertive diplomatic behaviour, and policies against religious minorities in Xinjiang. Changes in leadership and policies in previously friendlier foreign governments in the last calendar year – from Australia and Malaysia, to Sri Lanka – have also delinked China from some of its traditional allies. President Xi himself is facing at least some level of public scrutiny against the backdrop of a slowing Chinese economy and the effects of a bruising trade war with the U.S.

These challenges have in turn invited a deeper questioning of the top leadership’s new policy direction, as witnessed at this year’s Two Sessions.

China’s premier, Li Keqiang, delivered a report on the government’s work to the NPC delegates on the first day of the conference, and wrapped up the Two Sessions’ final day by fielding questions from foreign journalists, especially on the challenges facing China’s economy from downward pressures on growth, foreign investors’ concerns, and the trade war with the U.S. Premier Li’s report laid out China’s GDP growth goal for the year, along with other key targets for consumption, unemployment, and the deficit.

While Beijing has typically put its GDP growth target as a specific figure, this year it set out a target range of 6-to-6.5%, which will give Beijing greater room to manoeuvre as it seeks to stabilize the economy while also controlling its debt. Announced economic stabilization measures at the NPC meeting included lowered taxes alongside heightened currency regulations, while there are continuing moves by Beijing to ease supports for debt-heavy state-owned enterprises. China’s economy grew at 6.6% last year, exceeding that year’s target of 6.5%, but weaker than historic growth. For Canada, China’s shift in focus from high growth targets to deficit control and economic stability presents a risk to Canadian sectors that have been historically reliant on high growth in China: agri-food products, natural resource commodities, and vehicles, included.

New tools for trade disputes

The Two Sessions also gave China new tools in its ongoing economic disputes across the Pacific. China has already hit Canada’s agri-food sector with phytosanitary and other non-tariff barriers to exports to China, with more expected as the Canada-China diplomatic spat drags on. After Canada’s arrest of Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer for Chinese firm Huawei, Canada-China relations have chilled, with a number of retaliatory measures raised and proposed by China. China has also used tariffs in its trade war with the U.S.

These tariff and non-tariff tools have been historically limited to trade. But with the implementation of China’s new Foreign Investment Law during this year’s Two Sessions, and with more regulations on investment to come this year, China has legislated retaliatory measures into its foreign investment regime. Article 39 of the new law, for example, sets out China’s ability to bring “corresponding measures” to bear against investors from economies that have restricted Chinese investment.

Implications for Canada

The risk of these corresponding measures raises the stakes for Canada’s decisions on Chinese investment in Canada, both current and future, as the vagueness of Article 39 gives China the power to block new Canadian investors or expropriate existing investments by Canadians at its own discretion. Canadian federal investment law decisions on China’s investments have caused tensions with China in the past, and with an anticipated decision on whether to let China-based Huawei participate in 5G infrastructure rollouts across Canada, a “no” decision on Huawei could be enough to trigger Article 39 in China, with all that that could entail.

On the other hand, the NPC also approved an amendment to China’s Patent Law, affecting intellectual property rights protection by substantially increasing the range of fines for violators, with the NPC promising to back the law with stringent law enforcement. Whether this law, on its own, is enough to increase the Canadian tech sector’s confidence in engaging with China remains to be seen. Forced technological transfers – the process of forcing entrants into the Chinese market to surrender their technology to a local firm – by Chinese authorities on international entrants in the Chinese market have historically had a chilling effect on Canadian tech business confidence, and there are still many questions remaining about how the law will be enforced. Still, this amendment is one of the most visible measure by China to convince the international community that it is seeking to address an issue that continues to hamper China’s own ability to engage in the tech sector on the international stage.

One of the most popular Two Sessions announcements, at least among Chinese netizens, is the plan to lift at least 10 million people and 300 counties out of extreme poverty this year. By 2020, China expects to raise the country’s minimum annual incomes to 4,000 yuan (C$800). China continues to demonstrate its ability to raise mass populations out of poverty and into its expanding middle class – a class that has followed global middle class consumption patterns by asking for more, and better-quality, goods and services.

If Canada’s supply chains are able to link to this increased demand, it could pose significant opportunities for both basic Canadian commodity exporters and value-added exporters. If, however, China continues to retaliate against Canada during this current diplomatic spat, or if the ongoing U.S.-China trade war is resolved in a way that benefits American exports over Canadian exporters, then Canada may find itself locked out of the next stage in China’s economic journey, for good or ill.