If you are on social media (or even mainstream media), you’ve probably noticed that plant-based diets are very much in vogue, from the growing popularity and celebrity of health and wellness ‘experts’ on Instagram and widespread Canadian participation in ‘Veganuary’ (a voluntary pledge to eat vegan for January), to the Government of Canada’s new food guide released last week.

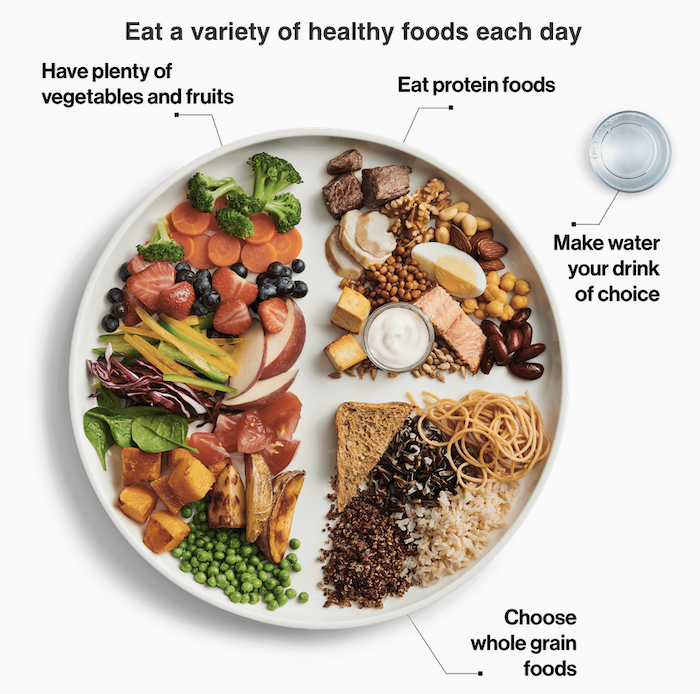

One of the more substantive changes to the Canada Food Guide, the first update to the national guide in more than a decade, is the recommendation to “among protein foods, consume plant-based more often.” This means minimizing meat and shifting to a greater consumption of legumes and pulses, such as chickpeas, lentils, and soy. It’s good for our health, our environment, and the economy – the Canadian prairies alone produces 65 per cent of the world’s lentils, mostly in Saskatchewan.

The Canada Food Guide's new healthy plate representation for 2019. Image Courtesy: Government of Canada

A notable update to Health Canada’s new food guide is the recognition that “nutritious foods can reflect cultural preferences and food traditions.” While this may have been written to make the guide sound less culturally prescriptive, it resonates because there is plenty of nutritional wisdom in culinary traditions the world over. Many of the plant-proteins the Canada Food Guide promotes (and that the prairie provinces grow) – chickpeas, lentils, soybeans – have been staples in Asia for centuries, if not millennia.

Considering better incorporating these ingredients into your diet? Look no further than Asia’s gastronomic traditions for some guidance. Here are three recommendations from the new Canada Food Guide, and suggestions from different Asian food cultures to help realize them in your own diet.

1. Be mindful of your eating habits

Japan offers some practical advice for reframing our relationship with food via the concept of washoku or, “the harmony of food.” UNESCO recognizes washoku as an intangible cultural heritage, a collection of the knowledge, skills and practices of Japanese food production. Part of washoku includes “Ittadakemasu” and “Gochisou-sama” – phrases that are said at the start and end of each meal, respectively, to express gratitude for the food. Regardless of the phrase used, habitually acknowledging your meal is one way to become more thoughtful about what it is you’re consuming.

Five is an important number in washoku, since each meal should delight the five senses, be prepared five different ways (raw, simmered, grilled, etc.), and should incorporate five colours. Without resorting to food-dye additives, challenging yourself to feature five different coloured ingredients on your plate will naturally lead to a more fruit and vegetable-laden diet.

2. Eat more protein from plants

India has such a complicated food landscape that it’s hard to identify a ‘national’ cuisine. Pulses, however, are enormously important to Indian diets – vegetarian or otherwise – so the closest thing to a national dish could be dal, the Hindi word for split pulses, often lentils, or the dish made primarily from these ingredients.

Lentils have been cultivated in India since as early as 1800 BCE.Of all legumes, lentils are second only to soy in terms of protein content. Paired with a whole grain, legumes are known as complementary proteins, or when two or more incomplete protein sources together provide all essential amino acids.

While you’re probably familiar with tofu as a meat alternative, you might not know about its Indonesian cousin, tempeh, which originated in Central Java sometime during or before the early 1600s. Because of the fermentation of whole soybeans in its preparation, tempeh has even higher protein and fibre content than tofu, and is the world’s richest vegetable-based source of B12. And due to its affordability, high nutrition content, and sustainable production methods, there is even a grassroots movement in Indonesia to popularize tempeh to combat malnutrition in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

If you’re looking to switch to a more plant-based diet, pair your whole grains and plant proteins and try experimenting with ingredients such as tofu or tempeh. And consider preparing vegetables, fish, and plant proteins with flavourful ingredients, such as shoyu (soy sauce), Chinese black bean sauce, or Thai green chili paste, available in most major grocery stores. For an even wider range of product choices, give your local Asian grocer a visit.

3. Food skills and food literacy

As the Canada Food Guide suggests, “cultural food practices should be celebrated.” Doing so encourages the transfer of culinary knowledge, expands a person’s cooking repertoire, and enhances cross-cultural fluency.

The Lunar New Year is around the corner, this year landing on February 5th. In the Chinese and Korean traditions we are entering the Year of the Pig, while in the Japanese tradition we’re about to start the Year of the Wild Boar. If you don’t already have meal or dining plans, consider using the Lunar New Year as a reason to learn something new about Asian food culture.

Consider making a (Lunar) New Year resolution to follow the food guide’s advice by trying something new – whether that’s cooking with an unfamiliar ingredient, such as lentils or tempeh, applying a washoku mentality to mindful eating, or learning how to wish someone a happy new year in the universal language of food.