If the events surrounding the signing of the recent USMCA trade agreement have taught Canadian businesses anything, it’s that we need to continue diversifying our trade interests. While it’s easy to rely on the U.S. given its close proximity and similarities in cultures, too heavy a reliance can lead to panic when ties between our two nations sour. The Asia Pacific is not only a smart location for Canada to diversify away from its overreliance on the U.S., but it is also a wise region for Canada to prioritize given its growing economic importance. Over the next 30 years the Asia Pacific region will come to account for both the majority of the world’s population and its economy. Canada needs to plan now for how to increase its market share in this booming region’s economy. Below are some of the important trends underpinning the Asia Pacific’s develop between now and 2050. These trends will impact the world and Canada in particular.

Trend 1: East Asia is Aging While South Asia is Growing its Working-age Population

It should come as no surprise that Japan is home to a large elderly population – the island nation is currently home to the most people aged 100 and above. But other Asian economies are starting to show some gray as well, with some countries recently becoming members of the World Health Organization’s ‘Aged Society’ club – defined as countries with 14 per cent of the population or more over the age of 65. In 2017, South Korea joined the club and Taiwan followed suit in 2018.

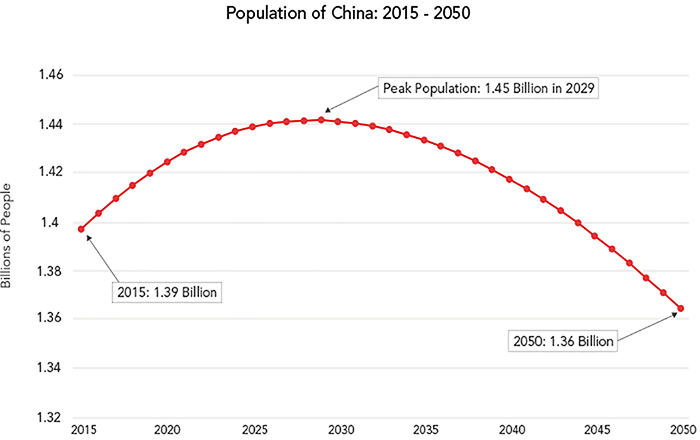

Something that gets lost in talks about trade and politics is the fact that China is also poised to be an Aged Society by 2027. By 2029, China is expected to reach its peak population, according to the UN’s Population Division. Between that peak and 2050, China’s population is estimated to shrink by approximately 77 million people. While this absolute loss in people may not be overly significant given China’s population of 1.4 billion, what it forebodes will impact not only the composition of the Chinese economy, but also the world economy.

An aging China could lead to a rearrangement of government spending as its pension system isn’t as developed as the systems of other aging societies. This could jeopardize future potential economic growth as money earmarked for fiscal stimulus may end up funding pensions instead. More generally, it could also mean a rise in wages for workers. As the employment pool shrinks, resulting from a rapidly aging and declining population, firms will be pressured to increase wages to incentivize employees to stay with a company. While this may sound great for workers, it will likely result in higher prices for consumers as rising production costs are passed on to consumers. Given China’s role in the global value chain for goods such as home electronics, this could mean higher prices for consumers around the world.

Conversely, by 2050 India will be home to over 663 million people aged 30 or younger, and this youth bulge is expected throughout most countries in South and Southeast Asia.

This situation – an aging East Asia and a youthful South/Southeast Asia – will ultimately result in a flow of young working-aged people from South Asia to East Asia. As East Asia exhausts its options to fill labour shortages domestically, it will have to begin looking beyond its borders for solutions. To facilitate this demand East Asian countries could provide visa exemptions for youth from countries like India to help fill labour shortages caused by declining populations. Given the abundance of young working-age people right on East Asia’s doorstep, this could lead to new levels of co-operation between Asian countries never seen before.

Trend 2: Asia will Account for the Majority of the World’s Middle Class

China’s socioeconomic rise in the past decade has propelled millions from poverty to the middle class, and with GDP per capita rising throughout the region, according to PwC, it’s expected that the rest of Asia will follow suit. Asia is predicted to make up 65 per cent of the world’s global middle class by 2030, according to a Brookings report, making Asia the largest contributor to the global middle class. Supporting this trend, India’s GDP per capita is set to rise to nearly US$26,000 by 2050, up from US$6,600 today. Indonesia as well will see itself become the fourth largest economy over the same time period, overtaking Japan, among other countries, in the process.

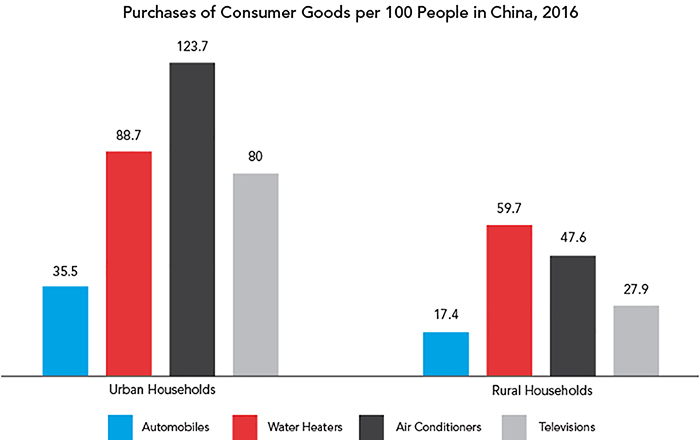

What this means is that people in Asia will be demanding not only more goods in general, but goods that are of higher quality and luxury goods from abroad. Currently we are seeing this in China through imported baby formula as people became upset with inferior domestic offerings. Vehicle purchases are another indicator, as luxury vehicle manufacturers like Land Rover and BMW are exporting more vehicles to Asia today than to North America.

Trend 3: Internal Migration to Cities will Create Cities Across Asia with Populations Larger than that of Canada

In line with the economic growth outlined above, a common symptom that underlines these new demographic trends is people moving away from small towns and into larger cities or urban metropolises in pursuit of greater economic opportunity. We’re currently seeing this in China as more people move from farms and villages to bigger cities. By 2050, China and India will have nearly two billion people living in urban areas, representing an increase of 800 million people combined between the two countries. This trend is also expected to extend across developing Asia as urbanization rates increase by an estimated 20 percentage points on average over the next 30 years in South and Southeast Asia.

As more people move into houses and apartment buildings, purchases of household durable goods such as TVs, refrigerators, and washing machines are expected to increase. This also means that there will be a further increase in demand for energy to power these new appliances. This could have great implications for developing Asia as countries in the region are already grappling with poor environmental conditions as coal continues to be the go-to choice for energy production.

What Does this Mean for Canada?

With Asia set for significant structural changes from now and through 2050, Canada needs to start positioning itself to take advantage of these developments. For example, Canada can continue to solidify its reputation as a destination for world-class education by attracting youths from South Asia. Canadian universities are already a popular choice among international students, as 64 per cent of the over 494,000 international students enrolled in Canada in 2017 came from the Asia Pacific and three of the top six growing countries of origin were in developing Asia. Aside from the C$2.8 billion in additional tax revenue added by international students, being able to offer certification in skilled labour will also help Canada maintain a pool of young and talented workers as more baby boomers enter retirement.

Meanwhile, for Canadian agriculture companies looking to expand into the Asian market, the timing couldn’t be better. Canadian farmers who pride themselves in producing safe, high-quality produce and fertilizers should be able to easily gain a foothold in the emerging Asian market as people look to demand more high-quality foods in line with their rising income. Canadian wheat, for example, has been a staple in Japan and South Korea given its high quality. As incomes rise throughout Asia, it’s expected that more countries will begin demanding Canadian wheat. In fact, mills in Indonesia have already begun buying wheat from Canadian farms.

With BP predicting that China will triple its natural gas consumption while India and emerging Asia increase natural gas consumption by 75 per cent by 2040, the recent approval of the Kitimat LNG pipeline is a step in the right direction. This project will allow for the facilitation of natural gas exports to Asia in line with the expected increase in demands.

Clean-tech is an another area where Canadian companies stand to benefit with increased engagement in Asia as China, for example, begins to diversify away from its reliance on coal to combat climate change and air pollution, while India is expected to reach peak-coal consumption by 2027.

The changes expected to take place in Asia on the way to 2050 will be extensive, especially as the populations and economies in North America and Europe mature. Rising populations in South and Southeast Asia alongside rising incomes throughout Asia and the growing popularity of urban city living all have the potential to create opportunities for Canadian businesses looking to diversify or expand their portfolios.