Canada's Trans-Mountain Expansion Project (TMX) came online in May 2024, following construction that began in 2019. By connecting landlocked Alberta oil to ports in British Columbia, this pipeline enhances Western Canada’s oil maritime export capacity, allowing access to new markets in the Indo-Pacific. It marks a first step towards much-needed diversification of Canada’s oil exports beyond the United States.

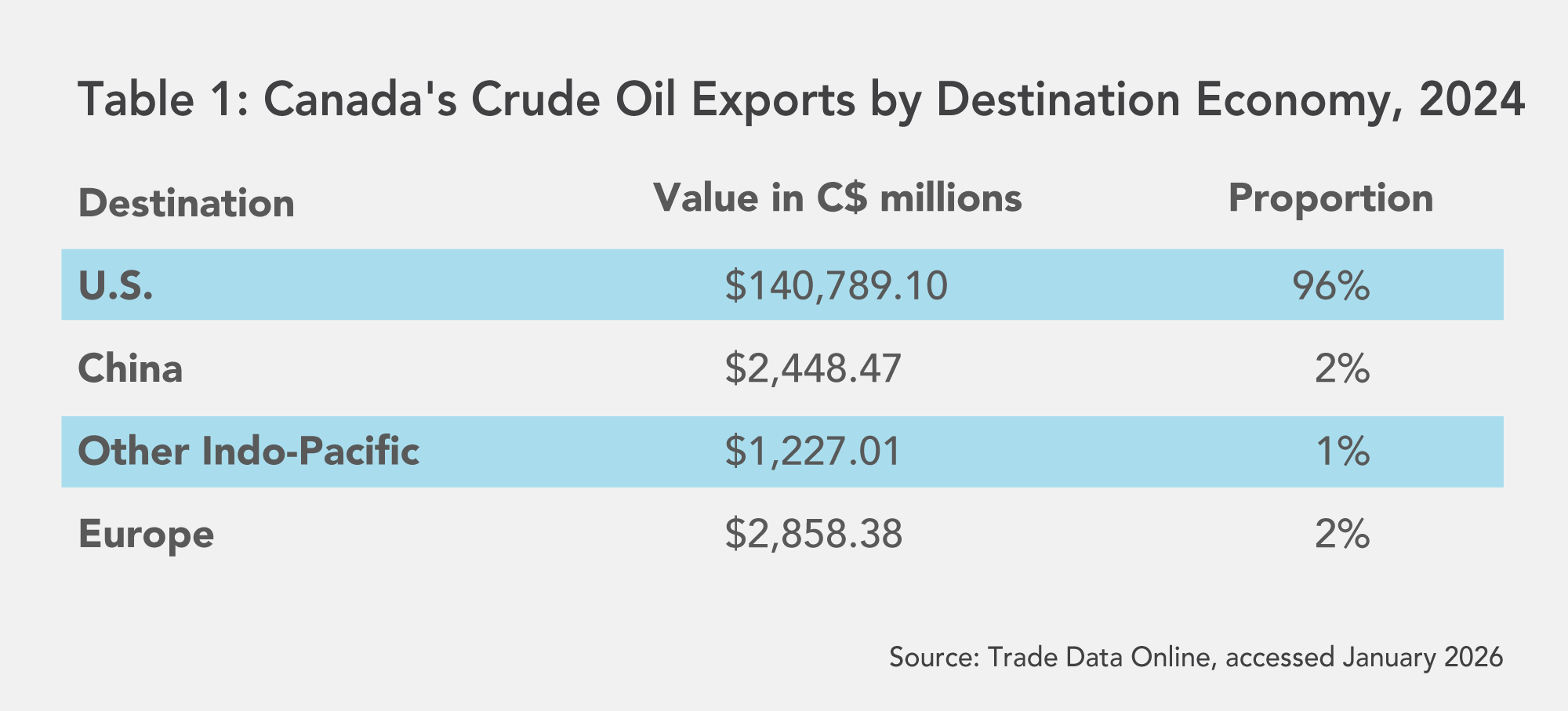

The first half of 2025 was marked by tariff threats, unprecedented economic uncertainty, and prolonged conflicts, sending oil prices up and down in a way more volatile than many had anticipated. Canada is the world’s fourth-largest crude oil producer with an output capacity of 5.76 million barrels per day, but 93 per cent of exports went to the United States in 2024 (Table 1). Canada’s oil is landlocked in Alberta and Saskatchewan, which have limited offshore export potential. While 76 per cent of global oil moves by marine transport, only 8 per cent of Canadian oil in 2024 was transported by marine, with more than 90 per cent flowing through U.S.-linked pipelines.

Amid Canada’s need for diversification, discussions around China’s role in Canada’s oil-exporting future have heated up. China is the world’s largest net crude oil importer, but it imports only about 1 per cent of its total oil from Canada. Since TMX became operational, China has become the top destination for Canadian petroleum in Asia, driven by strong demand and a pricing dynamic where Canadian producers secure higher prices compared to U.S. sales while Chinese refiners gain access to non-sanctioned crude at competitive prices. Yet, China’s trade relationship with Canada remains complex. Global pricing fluctuations alongside geopolitical and security considerations, as well as Canada’s own infrastructural challenges, could all dampen future oil sales. The industry’s resilience and sustainability in the long run will depend on Canada’s continued efforts to further diversify its export markets — many of which are in Asia — while investing at home to expand oil refining, shipping, and service capabilities.

TMX delivering results after overcoming challenges

The Trans Mountain Expansion Project was originally announced in 2013 to build a second, parallel pipeline to the existing Trans-Mountain Pipeline to increase transportation capacity. The expansion project faced significant regulatory hurdles and public opposition, prompting the Canadian government to acquire TMX from Kinder Morgan, an American energy infrastructure company, for C$5.5 billion (adjusted for inflation) in 2018 to ensure its completion in the national economic interest. Construction finally began in 2019, and, due to further delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was finally finished in May 2024, and represents a concerted effort by Canada to diversify oil exports to Asia and reduce its dependence on the U.S. Regardless of Canada’s current trade relationship with the U.S., American oil demand has plateaued since the pandemic, while demand in Asia, particularly in China, continues to grow.

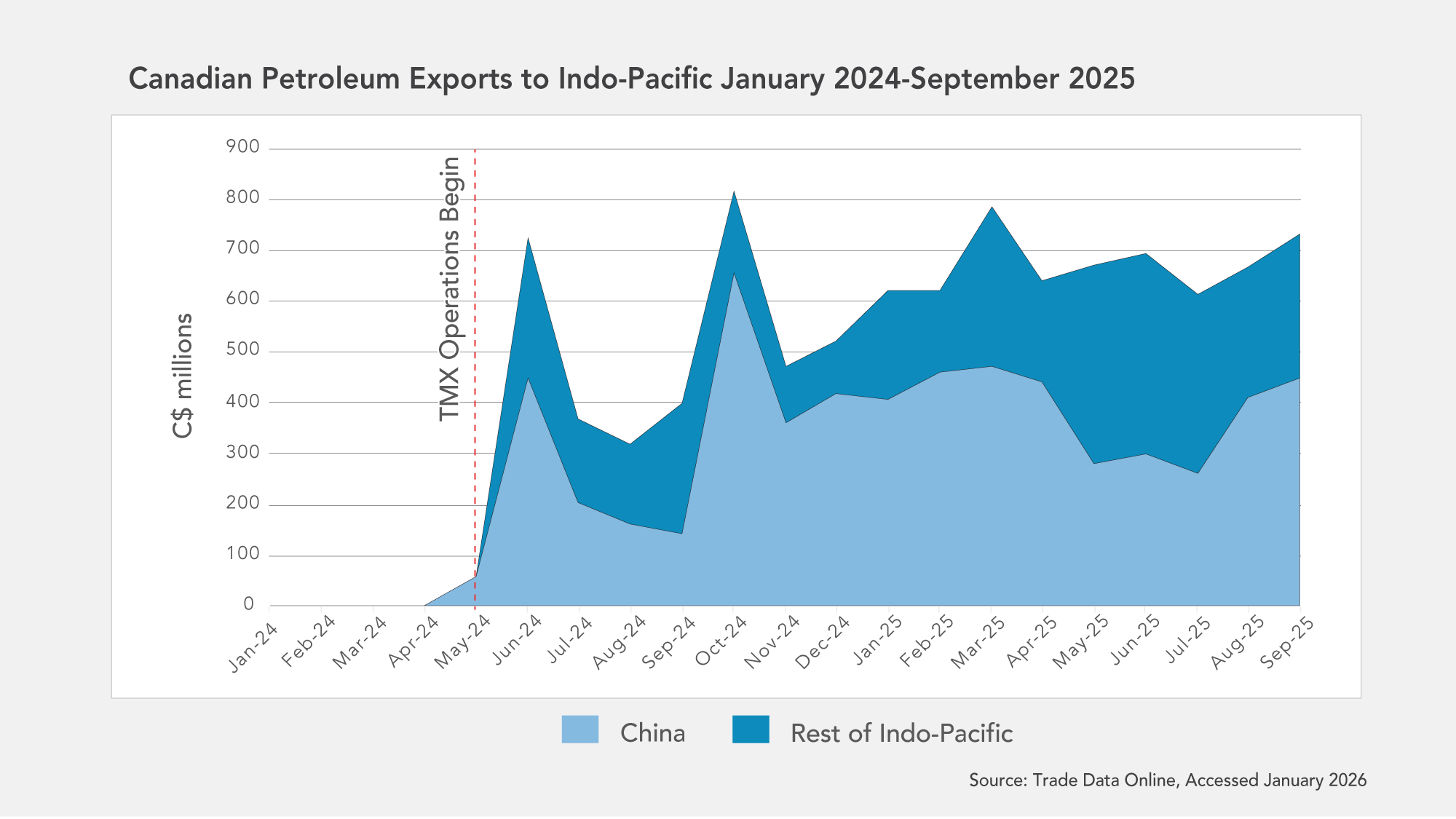

TMX has boosted pipeline capacity from 300,000 barrels per day to 890,000, and improved access to marine transport through the Port of Vancouver. Within its first month, the combined pipelines were already transporting 704,000 barrels per day — 81 per cent of its capacity. Between May 2024 and September 2025, crude oil exports to Indo-Pacific markets went from virtually zero to an average of C$571 million per month (Figure 1). China quickly became the second largest destination for Canadian crude after the U.S., with C$5.9B exported between May 2024 and September 2025, accounting for 61 per cent of exports to the Indo-Pacific and 3 per cent of global exports. Other new customers in the region included Singapore (C$1.6B), Hong Kong (C$1.5B), South Korea (C$411M), and India (C$158M).

TMX generates new export opportunities to China

For China, the new TMX pipeline represents an open route to purchase stable and affordable crude oil from Canada. China’s crude oil imports have experienced some dips due to the rapid adoption of electric vehicles, particularly in trucking, driving down demand for transportation fuels. However, oil remains crucial for petrochemical production and regional fuel refining. Plastics and synthetic fibres are also driving global oil demand. In March 2025, Beijing mandated a cap on new fuel refining capacity to reallocate crude refining capabilities to produce higher-value petrochemical outputs, such as plastics, synthetic fibres, and other chemical by-products, amid expectations of increased demand for such products. Privately-owned refiners responded to the government’s policy change, with Shandong Yulong Petrochemical Co. announcing plans to invest US$16.4 billion to expand its petrochemical production. However, record-high refined fuel project margins in mid-2025 encouraged refiners to use all existing export capacity and prioritize fuels despite the cap. This underscores China’s sustained demand for oil.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, China’s imports of Russian oil rose 26 per cent to 108 million tonnes in 2024, making China Russia’s top buyer, accounting for 47 per cent of Russian crude exports. Due to sanctions, China receives an average discount of US$15 per barrel off Brent ICE benchmark pricing. However, secondary sanctions and a narrowing discount could eliminate this advantage. China imported 19 per cent of its oil from Russia and 33 per cent from the Middle East in 2024, which leaves it exposed to geopolitical instability. To address this vulnerability, China has made efforts to diversify its crude oil sources, adhering to its policy of not importing more than 20 per cent of its crude oil from any single country. With Canada currently supplying just over 1 per cent of China’s imports, there is ample room for expansion to meet China’s energy security needs. Indeed, since May 2024, China has rapidly increased its Canadian oil imports, drawn by Canada’s cheap, non-sanctioned crude.

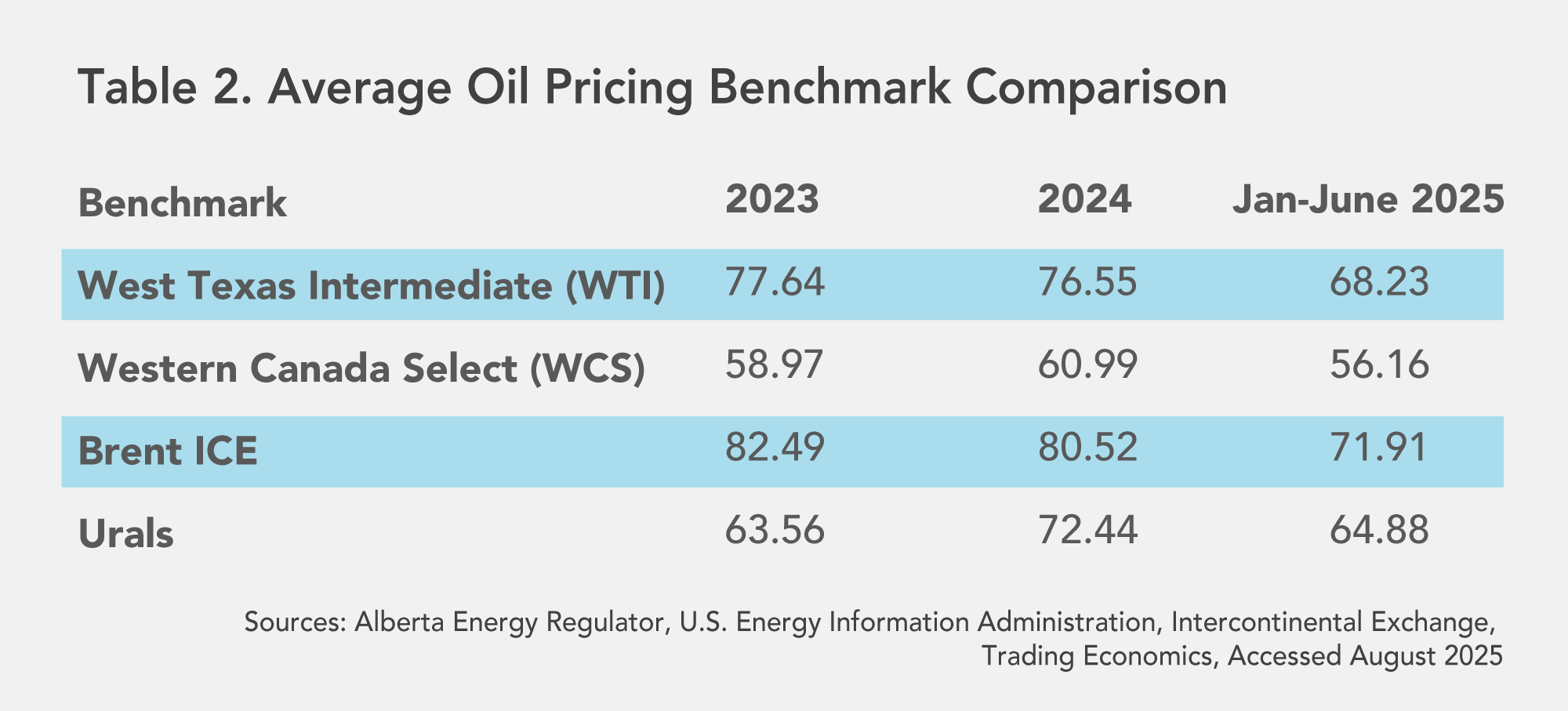

In selling crude to China, Canada benefits from how global oil prices are set. Oil exports to Asia Pacific markets, including China, are priced against the Brent ICE benchmark, which, on average, is higher than the Western Canada Select (WCS) used to sell to the U.S. (Table 2). As a result, Canadian producers fetch higher prices for Chinese oil sales than for U.S. sales.

Historically, Canada has sold oil to the U.S. at a discount of roughly US$10-20 per barrel discount compared to the U.S. pricing benchmark, West Texas Intermediate (WTI). (See Box 1). U.S. buyers have benefited from Canadian oil’s landlocked geography and heavier crude, which limited Canada’s export options and kept prices low. However, TMX’s improved access to Pacific ports has begun to challenge this dynamic: rising exports to China have narrowed the pricing difference between WTI and WCS benchmarks from an average of US$15 per barrel to only US$9.95 per barrel in June 2025—the lowest point since dipping to US$4.35 in 2020.

At the same time, China’s advanced refineries are well equipped to handle heavy, sulphur-rich crude oil. The result is mutually beneficial: Canada secures better revenues and greater market diversification while China gains a stable, low-cost oil supply.

Explainer: Oil Pricing

Crude oil prices depend on quality, location, and market dynamics, affecting what buyers are willing to pay. Lighter, “sweeter” oils with low sulphur content, such as West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent ICE, are easier to refine and trade at higher prices. In contrast, heavier, “sour” oils with high sulphur content, such as Western Canada Select (WCS), require more complex, energy-intensive refining and are sold at a discount to offset this extra expense. Location also plays a key role in pricing: WCS is landlocked in Alberta and constrained by pipeline infrastructure, thus limiting its customer base and causing producers to sell at a discount. Meanwhile, seaborne crude oil can fetch higher prices due to ease of delivery.

Canada and China’s oil trade has not only narrowed the WCS-WTI price discount but also renewed discussions over future pipeline projects. For Canada, Alberta’s production hit record levels in 2025, supported by TMX’s increased capacity. For China, Canada alleviates its ‘Malacca Dilemma,’ in which 80 per cent of its oil imports from the Middle East must transit the Strait of Malacca. North Pacific shipments are faster and more cost-effective than those through the Malacca Strait, or the Strait of Hormuz. This strategic advantage has revived interest in future Pacific pipeline projects, including renewed discussions of the long-stalled Northern Gateway pipeline to British Columbia’s Port of Prince Rupert.

Challenges and concerns about selling oil to China

Despite promising opportunities, Canadian oil exporters and policymakers face key challenges in expanding oil trade with China. One central concern is whether Canada can rely on China as a stable partner. As the world’s largest oil importer, China depends heavily on foreign crude, but can be a fickle buyer seeking the most cost-effective options. For example, while Saudi Arabia was China’s top supplier from 2019 to 2021, in 2023, China’s imports from Russia increased sharply, driven by sanction-driven discounts following the war in Ukraine. This shift highlights how quickly China’s trade preferences can change to meet its energy needs, potentially undermining Canada’s appeal as a secure, reliable supplier. To sustain exports, Canada must compete with Russia on pricing by offering net prices that offset longer shipping distances and higher transportation costs.

Moreover, geopolitics heavily shape Canada-China energy trade. Although China is Canada's second-largest trading partner and a major destination for natural resource exports, this relationship remains complex, often entangled with tensions around national security, human rights, foreign interference, critical technologies, and trade disputes. The recent tit-for-tat involving Beijing’s tariffs on Canadian canola seed following Ottawa’s tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles underscores concerns over economic coercion, and has prompted efforts to de-risk Canadian agricultural exports. Despite growing calls for a reset in Canada-China relations, managing and expanding commercial ties still requires a strategic approach.

Another major challenge for Canada is building domestic momentum for future pipeline projects. In November 2025, the Alberta and federal governments signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) committing to increased intergovernmental energy collaboration, including exploring the possibility of another pipeline to B.C.’s coast. However, B.C.’s provincial government and First Nations opposed the MOU, citing a lack of proper consultation. Additionally, coastal First Nations groups have opposed the project, citing the 2019 Moratorium Act that restricts oil tankers off B.C.’s north coast. In 2025, Indigenous communities maintained their stance restricting oil tankers — without Indigenous support, future projects risk inciting significant public opposition and possibly deterring future private-sector investments.

Exploring alternative markets in Asia

Given the uncertainties in both U.S. and Chinese demand for Canadian crude, it is crucial that Canadian oil exporters leverage TMX’s additional capacity and explore broader opportunities in the Indo-Pacific. Since the pipeline’s launch, exports to South Korea increased to C$306 million between May 2024 and 2025, up from virtually zero. Interest is also rising from Japan, which currently sources 95 per cent of its crude from the Middle East. India, which bought its first TMX shipment last year, may also need to soon reduce its intake of Russian oil due to narrowing discounts. Indo-Pacific refiners are particularly looking for substitutes for diminishing supplies of Venezuelan and Saudi Arabian heavy crude. Canada’s crude is a viable substitute for Venezuela’s heavy, sour crude, as refiners importing from Venezuela already have the necessary refining technology.

Tapping into these opportunities, however, will require overcoming several obstacles. Logistic challenges such as shipping time, tolls, and distance have historically contributed to low Canadian oil intakes in the region and may deter some Asian buyers. While there are globally leading refiners in countries like Japan, India, and South Korea that use Venezuela’s heavy crude, these countries’ refining capacities are still much lower than those of both the U.S. and China. These partners would generally prefer lighter crude that is easier to process, and are still evaluating the viability of Canadian oil, which makes WCS less attractive. Furthermore, Canada’s limited refining infrastructure makes the country more dependent on pipelines than other major oil-exporting nations, further constraining the range of export options.

Conclusion

With the TMX operating at 84 per cent of its capacity, industries are eyeing further expansion to help Canada boost crude exports to Asia. China is undoubtedly the biggest buyer, but significant limitations in the bilateral picture make the sustainability of this trade uncertain. At present, no other Asian economy appears capable of buying Canadian crude at volumes remotely comparable to the U.S. or China.

Canada’s oil diversification drive has always been constrained by transportation capacity, and now that this has improved, the more immediate question is whether Canada can address other challenges and fully tap into these emerging Asian markets. The enhanced pipeline offers a strategic opportunity for Canada to build off this momentum and effectively diversify its oil exports. The early success with China and other Indo-Pacific markets demonstrates the commercial potential of the TMX. Going forward, there needs to be co-ordinated policy actions to address the roadblocks in infrastructure, logistics, regulatory hurdles, and stakeholder engagement to seize this opportunity.

• Edited by Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, and Erin Williams, Director, Programs, APF Canada