The Takeaway

A March Cabinet Office survey revealed that approximately 1.46 million people, or two per cent of the Japanese population between 15 and 64, could be living as hikikomori (i.e. modern-day hermits) in the country. The large number of social recluses is considered a significant social issue in Japan, and the growing number of hikikomori has raised concerns in government and the private sector, especially as the country’s labour force continues to shrink.

In Brief

On March 31, the Japanese Cabinet Office released the 2022 “Survey on the Awareness and Lifestyles of Children and Young People,” which surveyed all age groups regarding the situation of hikikomori in Japan for the first time.

Hikikomori refers to both the people and the phenomenon of extreme social reclusion, which has been present in Japanese society for decades. The term can be directly translated to “pulling inward, secluding oneself” and it is often defined as acute social avoidance for a period of longer than six months. The broad definition presents challenges in accurately identifying hikikomori, as it may include those who share similar tendencies but do not fully meet the criteria. For these reasons, several exceptions were made in the study such as excluding individuals with schizophrenia, physical illnesses, housewives, and remote workers.

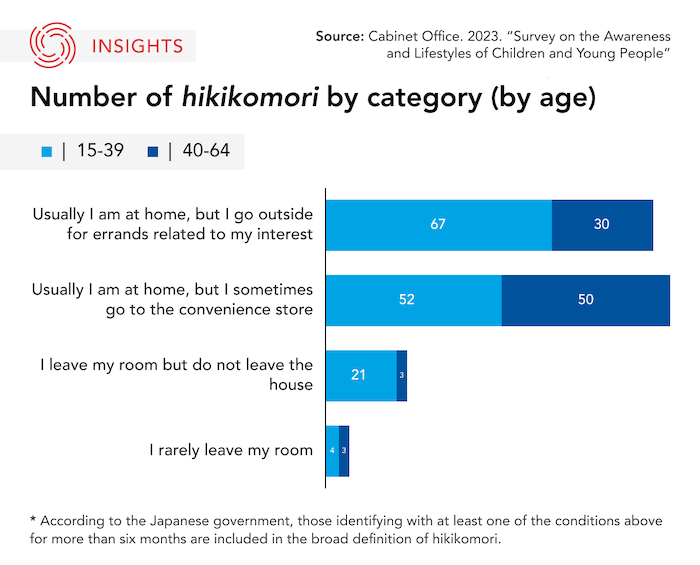

The survey was conducted from November 10 to 25, 2022, and garnered 13,769 responses from randomly selected people between the ages of 10 and 69. Under the government’s broad definition, 230 respondents (2%) within the working-age population (15 to 64) were categorized as hikikomori. Applied to Japan’s total population, the survey suggests that 1.46 million working-age people may currently be living in extreme social reclusion.

These findings highlight the growing problem of hikikomori in Japan, with a notable increase since previous government surveys. In 2016, there were an estimated 514,000 hikikomori between the ages of 15 and 39, while in 2019, there were roughly 613,000 hikikomori between 40 and 64. While the Cabinet Office cautioned against comparing previous estimates with the latest findings due to the differences in survey criteria, experts attribute the alarming increase in hikikomori figures to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have exacerbated loneliness and reclusion.

Implications

The term hikikomori was coined by a Japanese psychologist in 1998. Previously thought to be unique to Japanese society due to its rigid social structures, high expectations, and culture of shame, hikikomori is now recognized as a global phenomenon. Passionate and motivated individuals can become reclusive due to a combination of societal pressures, mental illness, and new technologies, making it a multifaceted phenomenon. Its study has increased in countries such as Canada and South Korea in recent years.

In 2010, the Japanese word hikikomori was added to the Oxford Dictionary of English after extensive reference in psychiatric literature. However, the features, criteria, and standards of hikikomori have consistently changed alongside studies and surveys on the phenomenon. While hikikomori was often associated with young men, recent studies have shown the extensive number of older hikikomori as well as the increasing number of women hikikomori, who accounted for 52.3 per cent for those between 40 and 64 in the 2023 survey. In response to these new findings, former female hikikomori-turned-advocates have praised the representation of women in the statistics and called for governments to implement women-specific hikikomori measures.

Modern technology, long seen as contributing to social isolation, is now being used (with great caution) to integrate hikikomori back into society. Several municipalities have begun creating online spaces for socializing, while also providing support for remote jobs. In Kyoto, the prefectural government launched an online meet-up program in June 2022, which organizes activities and conversations. School boards are also implementing similar programs to provide online education through the metaverse for students who have stopped going to school.

What's Next

- Global definition of hikikomori

While the existence of the phenomenon is acknowledged in many countries, the lack of epidemiological studies and the comorbidity of hikikomori with other mental illnesses have made it difficult to diagnose. Further studies to define the features of hikikomori should be made to include hikikomori in globally recognized lists such as the International Classification of Diseases.

- Increased government and civil society efforts to support hikikomori recovery

In 2018, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) established the Hikikomori Support Project, which created 85 “Regional Support Centers for Hikikomori” and local peer support programs. In January 2022, the MHLW also launched a new website to support hikikomori people, called the Hikikomori VOICE STATION. In addition, municipal organizations are expected to sustain their efforts to support hikikomori recovery.

- ‘New capitalism’ applied to hikikomori

In 2022, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio introduced the idea of “new capitalism,” which uses social issues to drive economic growth. The estimated 1.46 million hikikomori could be a dormant labour force, and their skills could be tapped through the ‘new normal’ of remote work. Companies that support hikikomori have called for government measures to create a new working style for hikikomori who could remotely work in vacant homes in rural areas.

• Produced by CAST’s Northeast Asia team: Dr. Scott Harrison (Senior Program Manager); Momo Sakudo (Analyst); Tae Yeon Eom (Analyst); and Sue Jeong (Analyst).