That the COVID-19 pandemic is hitting the Canadian economy is obvious: almost overnight, the concept of supply chains has been made both tangible and personal. Trade overall has suffered dramatic halts, with widespread production freezes and transportation restrictions. But trade in medical goods has been hit particularly hard, with national and regional governments, as well as businesses buying up or redirecting supplies and production for their own immediate needs.

With some of the earliest-hit countries in the Asia Pacific showing signs of recovery from the global pandemic, however, new supplies have emerged: South Korea, Taiwan, and China alone have sent hundreds of thousands of test kits and millions of masks overseas, with more promised.

Even so, the amount of newly-produced medical supplies is far outstripped by global demand. While more supplies are on the way globally, Canada is just one country among many (practically all) seeking to shore up supplies at a time when the importance of even one more mask could make a different on the frontlines of this indiscriminate disease.

We can expect that Canada’s imported supplies will face bottlenecks at a time of increased demand relative to previous years.

This piece looks at the types of medical supplies Canada has been importing from the Asia Pacific region. While Canada does not import all of its stock of these supplies from the region, the value of these imports has steadily increased across most types. With Asia Pacific economies fighting the emergence (or resurgence) of COVID-19 at a time when Canada is seeking to shore up its supplies, we can expect that Canada’s imported supplies will face bottlenecks at a time of increased demand relative to previous years. Reviewing the largest Asia Pacific-Canada linkages helps illuminate the disruption to this transpacific trade in medical supplies.

APF Canada examined the most vulnerable links between the Asia Pacific and Canada, in part courtesy of research and data from the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Innovation, Science and Economic Development and Statistics Canada’s Trade Data Online and Canadian Importers Database. With the federal government announcing measures to secure medical supplies on March 20, this review presents a potential roadmap to securing those most-needed supplies.

Our list of Canada’s medical supplies imports from the Asia Pacific was built by reviewing 17 categories of goods from the Asia Pacific’s largest economies based on their scale and potential disruption to Canada at a time when these goods are needed most.

Overall, 11 appear to have some level of risk, representing eight types of goods across four economies (some goods were at risk across more than one economy, while some economies also export more than one at-risk-good to Canada). Factors contributing to this list include the imports’ scale, growth (both absolute, and as a share of total imports), and the Asia Pacific economy’s share of Canada’s imports of that good, all considered against Canada’s domestic inventory.

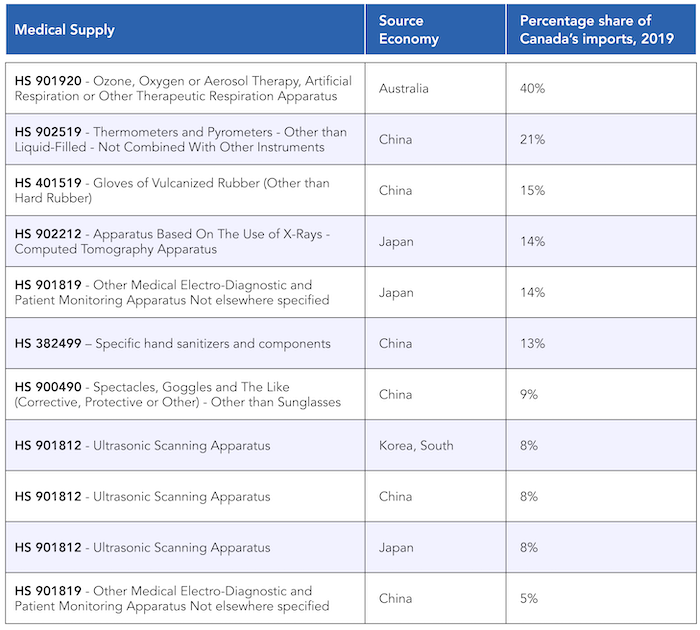

Some combinations of goods and source economies are especially notable given their size relative to Canada’s total imports.Some combinations of goods and source economies are especially notable given their size relative to Canada’s total imports and the increasing role these economies have played in Canada’s imports of that specific good over time. Oxygen therapy and artificial respiration ventilators, oxygen masks, and the like from Australia (HS 901920), and thermometers from China (HS Code 902519), make up significant shares of Canada’s total imports.

Following those two categories, Canada also imports important amounts of medical gloves from China (within HS Code 401519), medical goggles from China (HS 900490), patient monitoring systems for temperature, blood pressure, pulse, and the like from Japan (HS 901819), and hand sanitizers and associated chemicals from China (under HS 382499). Diagnostic ultrasound systems (used for diagnosing COVID-19, and categorized as HS 901812) from South Korea, China, and Japan, along with diagnostic CT scanners (HS 902212) from Japan, round out the list, with those economies playing a significant role in Canada’s imports of these two categories of goods.

Despite efforts by Canadian manufacturers to help meet the need for medical supplies and the goodwill of many Canadian organizations, data from the Asia Pacific tells us that during this time of pandemic, the challenges to Canada’s imports could also lead to impacts across multiple medical fronts. Disease prevention and mitigation in part requires goggles, gloves, and hand sanitizer, while the identification and diagnosis of the disease needs thermometers and diagnostic CT and ultrasound systems. Additionally, effective treatment requires artificial respirators and patient monitoring systems.

In the weeks ahead, medical officials will need to constantly evaluate where supplies are coming from, and where they are going, in order to co-ordinate the fight against the pandemic. Sporadic, local imports from the Asia Pacific region help, but Canada’s immediate needs demand more supplies, whether domestically-produced or imported. Some of the most important points to consider, in light of the gaps in these supply chains, are:

- Assessing where import inventory, especially inventory that has potentially been delayed or redirected due to the pandemic, has ended up within Canada. The Canadian Importers’ Database provides a guide to private-sector players in this space dating back to 2018, and efforts should be made within government and business to update a pandemic-specific list of supplies.

- The need to identify gaps at a more granular level, in terms of geographies. The location of supplies within Canada is just as important as determining what the total stocks are nationally. Once again, the medical policy community should be examining where importers are located, and the ability to shift supplies out of warehouses to transit if needed, using such databases such as the Canadian Importers’ Database.

- On the topic of granularity, there is a strong need to have better disaggregation of goods within these HS codes to better understand their medical uses. At the six-digit level, these broad categories cover non-medical goods as well, and our analysis has attempted (through cross-comparisons with other lists) to reduce those effects. However, in such a precise discipline as medicine, it is vital that we know the exact good being imported.

After excluding some combinations of goods and source countries due to small flows of trade or marginal shares in the Canadian market, the following table shows medical supplies and source economies, ranked by share of Canada’s imports.

With the federal government calling on industry and importers to help with the production and acquisition of medical supplies needed to fight COVID-19, Canadian industry and governments are in the process of examining the sudden shifts in Canada’s supplies at a time of increased demand. Canada’s guiding principles in the fight against this pandemic include both “evidence-informed decision-making” and flexibility in actions “as new information becomes available,” and understanding where Canadian supply chains are weak – and resilient – is no exception. In doing so, we may be better positioned to know when to procure, when to manufacture, and when to redistribute supplies against this indiscriminate enemy.

With the federal government calling on industry and importers to help with the production and acquisition of medical supplies needed to fight COVID-19, Canadian industry and governments are in the process of examining the sudden shifts in Canada’s supplies at a time of increased demand. Canada’s guiding principles in the fight against this pandemic include both “evidence-informed decision-making” and flexibility in actions “as new information becomes available,” and understanding where Canadian supply chains are weak – and resilient – is no exception. In doing so, we may be better positioned to know when to procure, when to manufacture, and when to redistribute supplies against this indiscriminate enemy.