Although the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) is now official, Canada should not let up on its push for more trade diversification. Canada’s federal government has taken a step in the right direction in setting a goal to boost our country’s exports by 50 per cent by 2025. This will mean extending Canada’s business presence into new markets, especially in Asia. To succeed in Asia, Canada needs people who know how to be effective operating in, and with, that part of the world. A 2016 survey of small- and medium-sized exporters in British Columbia gives us some clues to what that means in practice. Companies that export their products and services to Asia flagged as important skill sets that grow out of having cultural knowledge and first-hand experience in Asia. This includes the ability to develop and sustain relationships with partners in Asia (96%), an understanding of business etiquette (88%), culturally appropriate management of staff (86%), and having network of contacts in the region (79%).

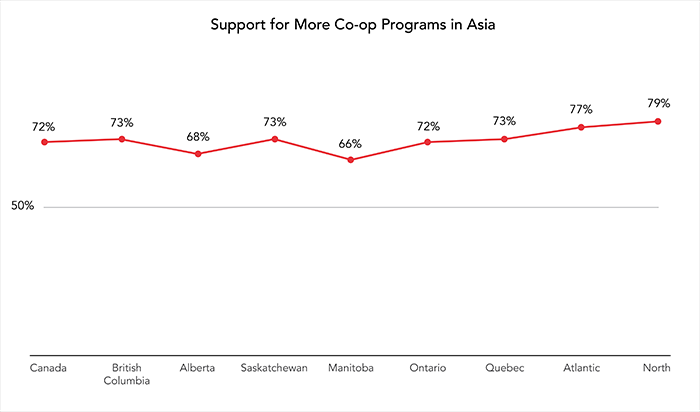

How do we equip more Canadians with these skills? One of the most efficient and well-tailored means for doing this is Canada’s co-operative (co-op) education program (or similar internships) that provides placements that are at least three or four months in duration. Such programs give students (and future business people) an immersive, hands-on experience in building cross-cultural professional relationships and helps them learn how to communicate and relate across cultural and language differences. The Canadian public recognizes the need for such programs: The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s (APF Canada) 2018 National Opinion Poll showed that large majorities across the country strongly support investing in more co-op opportunities for Canadians in Asia.

However, building a robust co-op system in Asia requires boosting not only the supply of opportunities, but also Canadian student demand for them. It also requires exposing students to Asia much earlier than post-secondary education.

Creating Work Experiences in Asia

Setting up co-op or other internship opportunities overseas takes considerable investment of time and energy. One of the most demanding aspects of this process is identifying and vetting potential employers. Fortunately, there are resources that can be tapped for this purpose. One is Asian alumni of Canadian universities, Asian international students who graduated from a Canadian university and then returned to their home country to pursue business opportunities. The upside of working with this pool of potential employers is that they will already be familiar with the quality of Canadian undergraduate education, and some will have even benefitted from the co-op program while they were in Canada. That should make it easier to enlist them and their companies to host Canadian interns.

Canadian businesses with operations in Asia are another source of internship opportunities. Their motivation may be legitimately self-serving: interns who can support the company’s present and future prospects in Asia could be the type of talent they would want to retain and invest in.

One obstacle to creating internships in Asia is the difficulty of obtaining student work permits. Some parts of the region, like Taiwan and India, do have programs for interns. Others, like China and South Korea, are much stricter, and students must operate in a ‘grey’ area that allows them to spend a few months learning on the job, but makes the issue of payment by employers a complicated one. Nevertheless, there are some Canada-wide programs that do provide either placement assistance or financial assistance for a wide range of internship experiences in Asia, such as AIESEC Canada, which offers volunteer, corporate, and startup internships in Asia, and the Mitacs Globalink Research Award, which provides funding for undergraduate students to do three-to-six month research internships in China, India, Japan, and Korea (along with many other graduate-level programs).

Boosting Student Demand

A more nebulous challenge to rapidly expanding our Asia-ready workforce is convincing young Canadians of the value of such opportunities. Several education organizations in Canada have raised the alarm about the need to rapidly increase the number of Canadian students with international experience. Universities Canada estimates that only 3.1 per cent of Canadian students study abroad annually (this includes short-term exchanges that last only a couple of weeks). Only a small fraction of those students ends up in Asia.

The reasons students do not take advantage of opportunities to get hands-on experience in Asia are varied and complex. The often-noted issue of cost should not be an issue if an internship provides at least a stipend to cover travel and living expenses. That leaves other factors that are more perceptual in nature, including perceptions that Asia is “too foreign,” that language will be an insurmountable barrier, and that the region is too dangerous. Another message that has surfaced anecdotally but consistently is the perception that work experience in Asia won’t be taken seriously by future employers.

Increasing student demand for work experience in Asia requires a full-throated counter-argument to these misperceptions. At a 2018 meeting of Asian and Canadian business leaders – the Asia Business Leaders Advisory Council – Canada’s Finance Minister Bill Morneau advised young people to think about, “What's my way to gain cultural understanding of places where there is going to be big opportunity in the future?” Such statements from Canadian leaders and influencers will be needed more than ever now that Canada is shifting into a higher trade-diversification gear.

Starting Early

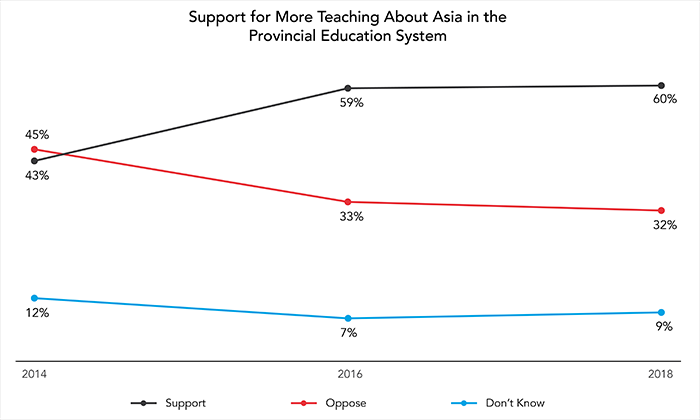

One of the most promising groups of leaders and influencers in Canada can be found at the local level – in the form of teachers, parents, and heads of school districts. At present, by the time many Canadian youth begin their post-secondary education, they have had relatively little exposure to Asia through their high-school curriculum. That is starting to change, including through an Asia-focused curriculum project undertaken by APF Canada and the BC Ministry of Education. APF Canada’s polling shows that a majority of the Canadian public supports teaching more about Asia in Canada’s schools. That support has been growing steadily.

Other communities that want to participate fully in the trade-diversification effort could signal to their local schools and provincial governments their desire to introduce students to the dynamic and economically vital region of Asia. This will be a powerful way for young Canadians to avoid or overcome the perceptual barriers about Asia being too foreign and too dangerous. By learning about Asian cultures, histories, and societies, as well as how their economies and politics work, students will follow Minister’s Morneau’s guidance, rather than foreclose future work experience opportunities in Asia as “not right for me.”

Conclusion

Getting the Canadian workforce better prepared to support the country’s trade diversification effort will take a serious and well-co-ordinated effort from leaders and influencers at all levels. It is difficult to see how we can reach the federal government’s target of a 50 per cent increase in exports within just six years if we don’t put the building blocks in place, and quickly. The investment of time and effort will be sizable, but the pay-offs will be even more sizable.

Read other blogs in our 2018 NOP Blog Series:

Introduction: Canadian Views on Asia: The 2018 National Opinion Poll Blog Series

Blog One: Are Francophones and Anglophones so Different in Their Views on Asia?

Blog Two: Energy Exports and Asia: Divergent Western Canadian Perspectives

Blog Three: Accessing Asia: Is Canada Falling Behind?

Blog Four: A Difference of Opinion: Canadian Provincial Views on Asia

Blog Five: More Exports to Asia Requires More Internships in Asia