Grey zone tactics are coercive actions that fall below the threshold of armed conflict, often exploiting ambiguity and asymmetry to achieve strategic goals while avoiding open war.

Grey zone tactics are coercive actions that fall below the threshold of armed conflict, often exploiting ambiguity and asymmetry to achieve strategic goals while avoiding open war.

In addition to significantly expanding its military capabilities, China increasingly employs grey zone tactics in the maritime domain to alter the status quo. This dynamic extends under the sea, where China could leverage asymmetry in combat. Of particular concern are its developing capabilities and practices in seabed warfare—operations that specifically target underwater infrastructure critical to its adversaries.

The exponential rise of internet data traffic, of which an estimated 99 percent relies on undersea cable infrastructure, has introduced a new layer of complexity and vulnerability to the maritime domain. The disruption of these vital underwater cables could have catastrophic consequences for the global political economy. Furthermore, the takedown of a target state’s connectivity would be multiplied if coupled with a conventional assault.

Yet, because these cables traverse multiple jurisdictions, establishing a comprehensive early warning system is challenging, and post-incident accountability is frequently entangled in complex jurisdictional disputes. The severe consequences of submarine cable disruption, combined with the difficulty in pursuing collective countermeasures, make underwater cables prime targets for asymmetric grey zone attacks.

These incidents of sabotage are part of Beijing’s broader maritime strategy. Over the past decade, China has systematically developed coercive tactics against neighbours including Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan. For Taiwan, subsea cables have a critical national security dimension because they are essential for economic prosperity, digital connectivity, and national resilience. This essay examines Taiwan’s vulnerability to undersea cable attacks, reviews the measures it has taken to address this growing challenge, and suggests ways Taiwan and other countries can strengthen their resilience in the face of such threats.

Taiwan’s Unique Vulnerabilities to Undersea Cable Attacks

Taiwan faces a disproportionately high rate of undersea cable disruptions, significantly exceeding global averages. While natural disasters or accidents cause occasional outages worldwide, at 0.1 to 0.2 incidents per cable annually, the statistics for Taiwan are stark. Specifically, the Taiwan–Matsu submarine cables experience an average of 5.1 damages per year—twenty-five to fifty times higher than the global average. For domestic submarine cables, Taiwan recorded thirty-six incidents of damage between 2019 and 2023, averaging seven failures annually, with a record high of twelve incidents in 2023. Furthermore, Taiwan reported five cable malfunctions in the first five months of 2025. This elevated frequency of incidents damaging underwater cables highlights Taiwan’s critical vulnerabilities, impacting its digital connectivity, economic stability, and overall national resilience.

The patterns of attacks on Taiwan’s undersea cables

In 2021 and 2023, two submarine cables linking Taiwan’s Matsu Islands were cut by Chinese-controlled vessels, causing multiday outages and raising concerns that they were deliberate tests of Taiwan’s response. Since then, suspicious incidents have multiplied. In January 2025, a Chinese-operated freighter under a Cameroonian flag severed the Trans-Pacific Express cable, while the following month, a Togo-flagged vessel with a Chinese crew cut the Taiwan–Penghu No. 3 cable and was later prosecuted under Taiwan’s Telecommunication Management Act (TMA).

These incidents share significant patterns: All ships had Chinese crews and Shunxin 39 (the Cameroonian-flagged vessel mentioned above) is owned by a Hong Kong company with documented Chinese connections. All vessels carried flags of states blacklisted by the 1993 Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control in the Asia-Pacific Region, which targets ships that fail to meet international standards. All had multiple sets of Automatic Identification System (AIS), which were often shut off to make them dark vessels. In addition, all often changed vessel names. For example, Hongtai 58 was shown by AIS but it also used the names Hongtai 168 and Shanmei 7

These incidents reveal three structural problems: First, the perpetrators often use a flag of convenience to conceal the ship’s Chinese background, making accountability difficult. Second, repair operations of undersea cables are highly time-consuming, depending on weather conditions and the availability of international repair vessels. Third, Taiwan lacks independent cable repair capabilities and rapid backup mechanisms, exposing strategic disadvantages.

Damage to these undersea cables could cripple the island’s connectivity—a risk heightened by Taiwan’s proximity to major maritime routes and sensitive geopolitical contests. An extended data interruption would seriously undermine Taiwan’s high-tech economy and compromise defence readiness. The psychological impact could be the erosion of public confidence and societal destabilization.

Taiwan’s Strategy to Address Submarine Security Challenges

Domestic law amendment

After the 2023 Matsu incident, the Taiwanese congress passed an amendment to Article 72 of the TMA in June 2023, expanding the scope of punishable offenses to include the destruction of submarine cables and increasing the associated penalties.

However, different maritime zones involve complex legal and jurisdictional frameworks based on international conventions, such as the Convention for the Protection of Submarine Cables and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and relevant domestic laws. These international conventions indicate that if a foreign-flagged vessel damages a country’s submarine cables outside of its territorial sea, the state does not have judicial jurisdiction.

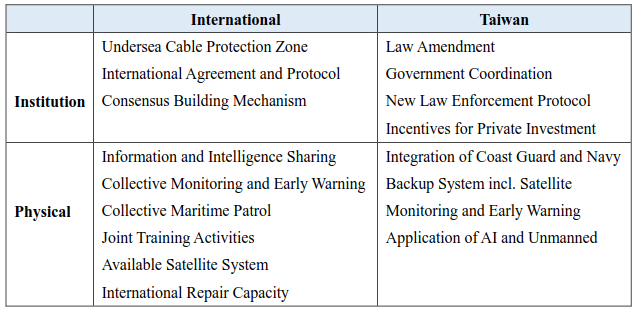

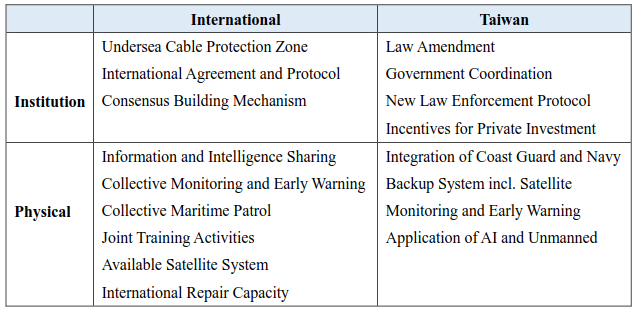

Table 1. Taiwanese and International Efforts to Improve Undersea Cable Resilience

Regarding cases where vessels involved in cable damage are registered in China, Article 75 of the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area provides that if the perpetrator is a Taiwanese citizen, Taiwan maintains judicial jurisdiction regardless of the maritime zone of the incident. However, if the perpetrator is a Chinese national and the incident takes place on the high seas, there is currently no clear consensus on cross-strait jurisdictional practice.

Government coordination to strengthen monitoring

On January 6, 2025, Taiwan’s Ocean Affairs Council (OAC) convened the Coordination Meeting on the Investigation and Advancement of Measures for Submarine Cable Damage. It reached a consensus to develop protective mechanisms to respond to submarine cable incidents, including standard responding and reporting procedures, as well as task allocations.

The Ministry of National Defense has cooperated with the Coast Guard Administration on Submarine Cables Protection and Standard Incident Response, aiming to enhance real-time monitoring incidents. For example, military forces could be mobilized to help intercept vessels that are categorized as medium-to-high threat and that are resisting interception.

The need to integrate high-tech for monitoring and early warning

Given the vastness of the maritime area and the limited availability of resources, smart technologies should be used to their fullest extent in monitoring, early warning, reporting, and collecting evidence on submarine cable incidents. Through the deployment of early-warning radar systems, satellites, underwater detection technologies, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), a comprehensive three-dimensional sea and air surveillance system can be established. This would allow the authorities to rapidly assess the situation, issue timely warnings, assist in reporting, and collect evidence effectively. When a submarine cable is severed, an alert would be triggered immediately, making real-time interception and arrest technically feasible. Therefore, establishing standard operating procedures for reporting and evidence collection among telecommunications providers, the Coast Guard, and prosecutorial offices is an urgent priority.

Public-private partnerships to diversify backup networks

In recent years, Taiwan has bolstered its undersea cable infrastructure with a comprehensive strategy. The government is offering incentives to telecom operators to build more cables, creating crucial redundancy across its network. It has also implemented a multitiered, heterogeneous backup system, significantly expanding microwave-communication capabilities to provide alternative pathways. Additionally, a dedicated budget is allocated for the planning and construction of a new Taiwan–Matsu cable, reinforcing a vital link. Critically, all fourteen international and ten domestic submarine cables are now designated critical infrastructure, ensuring heightened protection standards. These comprehensive measures aim to substantially reduce the risk of crippling disruptions, bolstering Taiwan’s national connectivity and overall resilience against future threats.

In an extreme scenario in which all submarine cables are severed, satellite communication emerges as Taiwan’s paramount backup. Chunghwa Telecom, Taiwan’s largest provider, secured an exclusive agreement in 2023 with OneWeb to set up 700 user terminals and three overseas ground stations (in Japan, Thailand, and Guam) to create the only non-geosynchronous backup with long-term growth potential. Chunghwa Telecom also uses SES O3b mPOWER’s second-generation MEO (Medium Earth orbit) satellite systems to secure critical government, financial, medical, and corporate communications.

Alternative systems carry risks: Starlink is geopolitically sensitive due to Elon Musk’s stance on China, and Amazon’s Project Kuiper is not yet operational. To meet its 3 Tbps (terabits per second) backup target, Taiwan will need 60–80 ground stations, relying on a hybrid Low Earth Orbit (LEO)/MEO approach with multiple providers to ensure resilient wartime communications.

International Efforts to Secure Undersea Critical Infrastructure

Undersea-cable protection zones

Even as the recognition of submarine cables as a global public good continues to rise, traditional legal frameworks are falling short in addressing their security. Therefore, in addition to imposing heavy penalties upon the perpetrators of incidents that cause damage to cables, many countries have also begun introducing legislation for prevention. One notable approach is the establishment of submarine-cable protection zones, where the government designates a corridor along the cable route and strengthens aerial and maritime patrols within the zone, while restricting activities in those waters to safeguard cable security. New Zealand’s Submarine Cables and Pipelines Protection Act of 1996 designated ten submarine-cable protection zones, while Australia’s 1997 Telecommunications Act established three such zones. Australia’s protection-zone model has also been praised by the International Cable Protection Committee as one of the most comprehensive legal frameworks of its kind in the world.

International agreement and collective actions

Taiwan is actively aligning with global efforts to protect undersea cables. In late 2024, the seventy-ninth session of the United Nations General Assembly issued the “New York Principles,” highlighting the critical role of submarine cables in global commerce and digital development. This statement affirmed a collective commitment to safeguarding and strengthening this vital infrastructure.

Taiwan can capitalize on this global momentum by promoting these principles internationally and sharing its extensive experience with frequent cable disruptions. Furthermore, Taiwan’s neighbours that also face similar grey zone threats from China should engage in intelligence sharing and cooperation. This collaboration can lead to more successful tracking of suspicious vessels and facilitate necessary boarding inspections. Given the high frequency of grey zone threats in the waters surrounding Taiwan, actively pursuing the establishment of, or participation in, international platforms for maritime intelligence sharing and cooperation against these threats is a viable future strategy.

Significantly, on July 9, 2025, the US Senate introduced the Taiwan Undersea Cable Resilience Initiative Act. The initiative aims to deploy real-time monitoring systems, develop rapid-response protocols, enhance maritime surveillance, and improve international cooperation against sabotage to bolster cable resilience near Taiwan. This US legislative effort, coupled with Taiwan’s own proactive engagement and regional partnerships, marks a crucial step toward enhancing the security and resilience of vital undersea communication lifelines in the Indo-Pacific.

Strengthening Undersea Resilience

The recurrence of maritime incidents involving the sabotage of submarine cables is not random but reflects a deliberate, multifaceted Chinese strategy aimed at maritime dominance. For Taiwan and other regional states, simply enhancing monitoring is insufficient. Countering Chinese action salso requires diplomatic coordination, diversified communication pathways, and swift repair capabilities.

As Indo-Pacific tensions escalate, policy-makers from around the world must acknowledge these grey zone maritime activities as integral to China’s broader strategic framework. The security of critical undersea infrastructure will be increasingly central to regional planning. This demands innovative defensive measures and robust international cooperation to ensure resilience against this evolving threat.

Global efforts to protect undersea cables and respond to sabotage remain nascent. The immediate priority is for navies and law enforcement to be fully aware of the threat and vigilant about activity near cables. Beyond that, like-minded countries must collaborate: exchanging intelligence, sharing best practices, and operating cooperatively. More multilateral sea patrols would help offset the insufficient numbers of ships, submarines, and aircraft individual states can deploy to address these challenges.

Additionally, the command centres dispatching vessels and crews need better training on this new threat dynamic. This will require legal and regulatory reform. Governments also need to expand partnerships with the private sector: to grow repair fleets in anticipation of a sustained campaign against cables and to ensure sufficient bandwidth redundancies for critical information. As a high-tech society at the forefront of this threat, Taiwan has an opportunity to demonstrate leadership, not only to advance its own interest but to serve much of the world.

Yujen Kuo, Institute of China and Asia-Pacific Studies, National Sun Yat-sen University

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has less than three years in office to meet the great expectations of his people for a New Philippines (

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has less than three years in office to meet the great expectations of his people for a New Philippines ( Grey zone tactics are coercive actions that fall below the threshold of armed conflict, often exploiting ambiguity and asymmetry to achieve strategic goals while avoiding open war.

Grey zone tactics are coercive actions that fall below the threshold of armed conflict, often exploiting ambiguity and asymmetry to achieve strategic goals while avoiding open war.

Conception: Chloe Fenemore/FAP Canada

Conception: Chloe Fenemore/FAP Canada